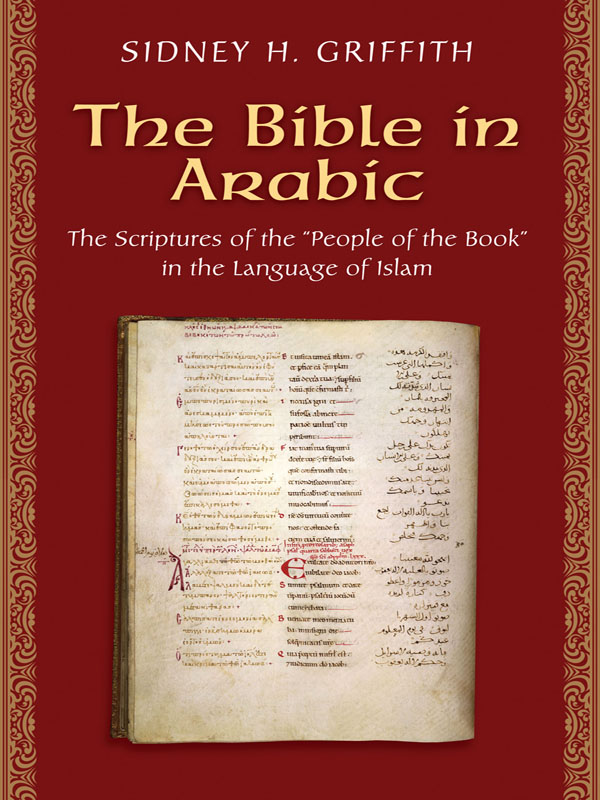

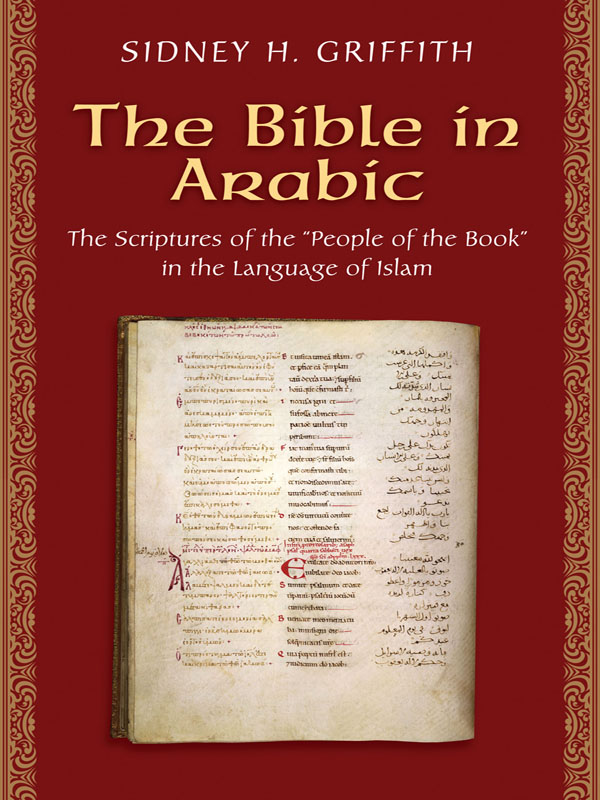

The Bible in Arabic

JEWS, CHRISTIANS, AND MUSLIMS FROM THE ANCIENT TO THE MODERN WORLD

Edited by Michael Cook, William Chester Jordan, and Peter Schfer

A list of titles in this series appears at the back of the book.

Copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art: Harley Trilingual Psalter, Palermo, Italy, between 1130 and 1154. Psalm 81(80). BL Harley MS 5786, f.106v. Copyright The British Library Board

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-15082-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Griffith, Sidney Harrison.

The Bible in Arabic : the Scriptures of the People of the Book in the language of Islam / Sidney H. Griffith.

p. cm. (Jews, Christians, and Muslims from the ancient to the modern world)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15082-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Bible. ArabicVersionsHistory.

I. Title.

BS315.A69G75 2013

220.4'6dc23

2012038720

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in ITC New Baskerville Std

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Dedicated to the memory of my brother, Michael Joseph Griffith

Illustrations

Illustrations

Preface

Preface

IN THIS ERA of scholarly specialization, one is intensely aware of his limitations and of his debt to scholars better equipped than he to address even so seemingly simple a topic as the Bible in Arabic. For the fact is that in every chapter that follows one must rely on the work of scholars who have made the particular subject of that chapter the focus of their own studies. To venture into such territory not immediately ones own does indeed give one pause. Yet the contribution one hopes to make in undertaking the adventure is twofold: first to call attention to the central role the Bible and biblical lore have played in the unfolding of religious thought in Arabic in Islamic times, from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages; and secondly to highlight the interreligious dimension of intellectual life in the Arabic-speaking world in the same period, even in biblical studies, albeit that it was often a discourse in counterpoint and nothing like the interreligious dialogue of which one speaks so readily in our times. But the fact is that religious and intellectual culture in the World of Islam in the classical period came together in a polyphony of voices in Arabic and the part of the Bible in that chorus, so often actually carrying the melody, has not received the broad recognition it deserves. It is the purpose of the present survey of the available scholarship to call attention to the historical, religious, and cultural importance of the Bible in Arabic, to encourage its continued study, and to provide some bibliographical guidance for the undertaking.

In writing this short book I have profited immensely from a semesters residence at the Hebrew University of Jerusalems Institute for Advanced Studies at the invitation of Professor Mordechai Cohen of Yeshiva University and Professor Meir Bar Asher of the Hebrew University. The group they assembled there to study the cross-cultural reading of the Bible in the Middle Ages provided the opportunity for a daily colloquy with a community of scholars for whose counsel and inspiration I am profoundly grateful. Where else in the world could I go just next door to Meir Bar Ashers office with my problems in Arabic, or down the hall to Meira Polliack for guidance in Judaeo-Arabic and the history of Karaite biblical study, or around the corner to James Kugel for advice on interpretive strategies? Other scholars too have readily given me their help and advice. I thank in particular Prof. Alexander Treiger of Dalhousie University for much advice and bibliographical help, Dr. Ronny Vollandt for sharing with me his just finished and very rich doctoral dissertation on the Pentateuch in Christian Arabic, and Dr. Adam C. McCollum of the Hill Monastic Library in Collegeville, MN, for his very helpful and still growing bibliography of the Bible in Arabic. I give thanks too to the publishers readers who provided insightful comments on the original proposal for this book. I am grateful to Prof. Christine M. Bochen of Nazareth College of Rochester, New York, who has sustained my work every step of the way. I thank Fred Appel, Sara Lerner, and Sarah David of the Princeton University Press for their constant solicitude and ever-ready kindness to me as I prepared my manuscript for publication and Eva Jaunzems whose superb copyediting has immensely improved the readability of my book. In my own academic home, The Catholic University of America, I am much indebted to the support of my colleagues, Dr. Monica J. Blanchard, the curator of the Semitics/ICOR library, Dr. Janet Timbie, Dr. Shawqi Talia, Dr. Andrew Gross, our chairman Dr. Edward Cook, and Mr. Nathan Gibson, who prepared the bibliography and proofread the footnotes. Finally, I wish to express my gratitude for the support and interest of my family and friends throughout the long time I have been distracted by this project. I owe special thanks to Marlene Debole who supported and encouraged this project.

I have approached the study of the Bible in Arabic from the perspective of a historian of Christianity in the Middle East, particularly in Late Antique and Early Medieval times, and especially as that history is disclosed in texts written in Syriac and Christian Arabic. Working from this perspective involves approaching the Arabic Qurn, the career and teaching of Muammad, and the birth of Islam from the unusual angle of one who encounters them a parte ante, in the course of following the trail of Jews and Christians into the Arabic-speaking world. When on this tack one meets with the newly arising Arabic Qurn, the Bible in the Qurn, and a conspicuous amount of other Jewish and Christian lore, these phenomena appear in a somewhat different light than they do when viewed from the perspective of a researcher who looks back at the rise of Islam from after the fact, and strives to see it in its historical context, as most historians of early Islam do. For one thing, from my perspective the Arabic Qurn looms into view as just about the only document in any language that offers me an insight into the Jewish and Christian presence in the Arabic-speaking milieu in the first third of the seventh century. What is more, what I see there as a historian of Christians, their beliefs, and practices, is a remarkable continuation mutatis mutandis of both topics and modes of discourse, albeit that in the Qurn they appear in a translated, refracted context not so much of congruence as of critique and interreligious polemic. As for the Bible itself, its pervasive presence in the Qurn, notwithstanding the almost total want of quotations, bespeaks a strong oral presence of the Bible in Arabic in the Arabian ijz in the first third of the seventh century. It would not be long before, in the wake of the codification of the Qurn, and the twin processes of the Arabicization and Islamification of life in the territories occupied by the conquering Arabs in the later seventh century, Jews and Christians would begin to produce written translations of biblical books and to circulate them in Arabic. This book aims to call attention to the story of how the Bible came into Arabic at the hands of Jews and Christians, and how it fared among Muslims from early Islamic times into the Middle Ages.

Next page