Alexander Bevilacqua - The Republic of Arabic Letters: Islam and the European Enlightenment

Here you can read online Alexander Bevilacqua - The Republic of Arabic Letters: Islam and the European Enlightenment full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: Belknap Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Republic of Arabic Letters: Islam and the European Enlightenment

- Author:

- Publisher:Belknap Press

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Republic of Arabic Letters: Islam and the European Enlightenment: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Republic of Arabic Letters: Islam and the European Enlightenment" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

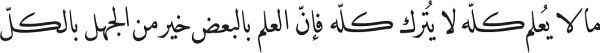

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a pioneering community of Christian scholars laid the groundwork for the modern Western understanding of Islamic civilization. These men produced the first accurate translation of the Quran into a European language, mapped the branches of the Islamic arts and sciences, and wrote Muslim history using Arabic sources. The Republic of Arabic Letters reconstructs this process, revealing the influence of Catholic and Protestant intellectuals on the secular Enlightenment understanding of Islam and its written traditions.

Drawing on Arabic, English, French, German, Italian, and Latin sources, Alexander Bevilacquas rich intellectual history retraces the routesboth mental and physicalthat Christian scholars traveled to acquire, study, and comprehend Arabic manuscripts. The knowledge they generated was deeply indebted to native Muslim traditions, especially Ottoman ones. Eventually the translations, compilations, and histories they produced reached such luminaries as Voltaire and Edward Gibbon, who not only assimilated the factual content of these works but wove their interpretations into the fabric of Enlightenment thought.

The Republic of Arabic Letters shows that the Western effort to learn about Islam and its religious and intellectual traditions issued not from a secular agenda but from the scholarly commitments of a select group of Christians. These authors cast aside inherited views and bequeathed a new understanding of Islam to the modern West.

Alexander Bevilacqua: author's other books

Who wrote The Republic of Arabic Letters: Islam and the European Enlightenment? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.