Inhalt

Giuseppe Veltri

A Mirror of Rabbinic Hermeneutics

Studia Judaica

Forschungen zur Wissenschaft des Judentums

Begrndet von

Ernst Ludwig Ehrlich

Herausgegeben von

Gnter Stemberger, Charlotte Fonrobert

und Alexander Samely

Band 82

ISBN 978-3-11-036837-6

e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-036641-9

e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-043778-2

ISSN 0585-5306

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de .

2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

www.degruyter.com

To my daughter

Livia Filomena Ina

The craft of the word created the universe

, , , , , , , .

(Ps-Longinus, Per hpsous 8:9).

A missing letter can destroy the entire world

( Babylonian Talmud Eruvin 13a)

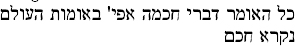

The intelligent word is universal

( Babylonian Talmud Megillah 16a)

Introduction

In considering the multifarious world of theoretical and empirical sciences, a Venetian rabbi of the XVII century, Simah (Simone) Luzzatto, wondered about the reliability of the images projected by the mirror. According to him, although mirrors are constructed on the basis of the same material, they reflect the images in different ways in their shapes. The reason for the different reflection cannot be due to the object, because they reflect the same object; therefore one has to infer that the perceived difference depends on the receiver, i.e. the eyes (or the reflective surfaces of the mirrors). The different visions of reality and hence also the fallacy of realities, depend on the receiver.

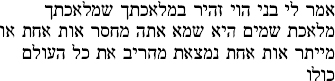

Jerusalem Talmud, Shabbat 6,1 (7d) contains an interesting tradition:

Three things were allowed to the members of the House of Rabbi: that they look at oneself in the mirror; that they trim ones qomi , and they teach Greek to their sons. For they were close to the (Roman) government.

To look in ones mirror has nothing to do with hair trimming. It was a mantic practice ascribed to kings and emperors called specularia . The author of the Historia Augusta tells us that Didius Iulianus

was mad enough to perform a number of rites with the aid of magicians, such as were calculated either to lessen the hate of the people or to restrain the arms of the soldiers. For the magicians sacrificed certain victims that are foreign to the Roman ritual and chanted unholy songs, so we are told, before a mirror, into which boys are said to gaze, after bandages have been bound over their eyes and charms muttered over their heads .

Divination through a mirror is also considered here as a kind of art or science to be attributed to the structure of power. To look into the mirror is the expression of a structure of power strung between magic and politics, directed toward interpreting reality as it is, should be or as is politically convenient. The mirror is thus an instrument of power to act upon reality and world(s) of reference.

Both the mirror of multifarious hermeneutic reflections or epistemological imagination and the (magic) instrument of power are the main topic of this study. Rabbinic hermeneutics reflects this multifaceted world of the text and of reality, seen as a world of reference worth commentary. As a mirror, it includes this world but perhaps also falsifies reality, that is, adapting it to ones own aims and necessities.

The present study is the product of my research on ancient Judaism in the last 15 years. It consists of four parts: addresses the rabbinic concern with texts (IV: Reflecting on Languages and Texts ) as the main area of influence of the rabbinic academy in a space between the texts of the past and the real world of the present.

: Officina Rabbinica

Rabbinical texts are but fragments of past discussions and debates without fixed starting points or fixed termini. Talmudic texts are often a riddle to students as there is no consistent structure, no inherent style, and an apparent lack of methodology. This is rather surprising considering the centrality of teaching and learning, and the fact that instruction was the essence of these texts.

In order to understand the teachings of the rabbis these cryptic texts of rabbinic academies the student needs to resort to impertinent means and a certain degree of chutzpah . Only then, as I outline in this chapter, is the student able to access the texts. To raise up many disciples (Mishnah Avot 1:1), as the main aim of the teachers, sought to equip the students with the necessary skills to pose questions and thus to absorb the lesson by means of indirect education.

Hermeneutics is a perpetual method of reforming, i.e. of re-shaping the idea, the concepts, the imaginative grammar of the past (tradition) as mirrored by the transmitted texts. Martin Luthers Reformation garnered interest among Jews as well especially in the periphery of European Jewry where the later Lutheran anti-Jewish tractates never had an impact. However, the Reformation also sparked interest in Jewish reforms, such as those of the Karaites, whose understanding of Judaism bore similarities to the thinking of the Christian reformers. One of the most apparent reforms in Judaism before the nineteenth century was Ezras (re-)creation of the Jewish traditional literature as described in the bible and through the legend of the Septuagint. It was Ezras work which marked the transition from the creation of the Hebrew text to its interpretation, that is, to the realm of the rabbis.

Utilizing several instances of historical reforms concerning Judaism with an emphasis on Ezra I discuss in this chapter the nature of the reforms themselves. I explore the structures of reforming, and the strategy to promote new developments while standing firmly on the ground of tradition. Reforms are more than a mere challenge to existing texts by re-canonizing them. They supposedly constitute a mode of recourse to a Golden Age, with the explicit aim of justifying political and cultural changes. The reforms are manifestations of political changes sought through canonical change. Ezras story is the perfect example of this.

: Reflecting Roman Religion

Discussing the Roman occupation of Palaestina in antiquity, and the Jewish sources mirroring it, solely through the prism of military repression is too simplistic. Discussing it in a political-historical way or through the prism of a clash of civilisations likewise falls short. Judea had been a province of Rome (or Byzantium) for the better part of a millennium until the Muslim conquest. Thus, cultural-historical elements of Roman life customs and religious practices were a fact in the province, yet under the conditions of the military as the main representative in this part of Romes periphery. The cultural transfer from the Greco-Roman occupiers to the occupied Jews is a crucial aspect for understanding Jewish society in ancient Palaestina and the rabbinic texts reflecting it.

In this second section, I discuss the representation of Greco-Roman customs in rabbinic sources through the examples of the so-called darkhe haemori , the ways of the Amorites, and the Roman festivals as they were celebrated in the periphery of the empire. By doing so, I argue that these cultural aspects were not merely noted to present the follies of the Romans, or to draw a clear boundary between the Jews and the imperial occupiers. The representation often served the purpose of separating oneself from the Other, but also of absorbing new customs and mores into the armature of Jewish identity and culture such as the sphere of ones own holidays by a transformative process, giving them a new background and meaning. Yet that absorption and adaptation were always carried out under the condition of compatibility with ones own traditions. The cultural aspects of the Greco-Roman world as they are noted in the rabbinic sources were religious, social, and political reactions to the on-going process of common, everyday interaction between Jews and Greco-Romans, direct daily contact with their culture and identity. Essentially, the rabbinic sources provide proof of a crisis in culture and identity, and the struggle to preserve both under ones own conditions of Jewish tradition.