PREFACE

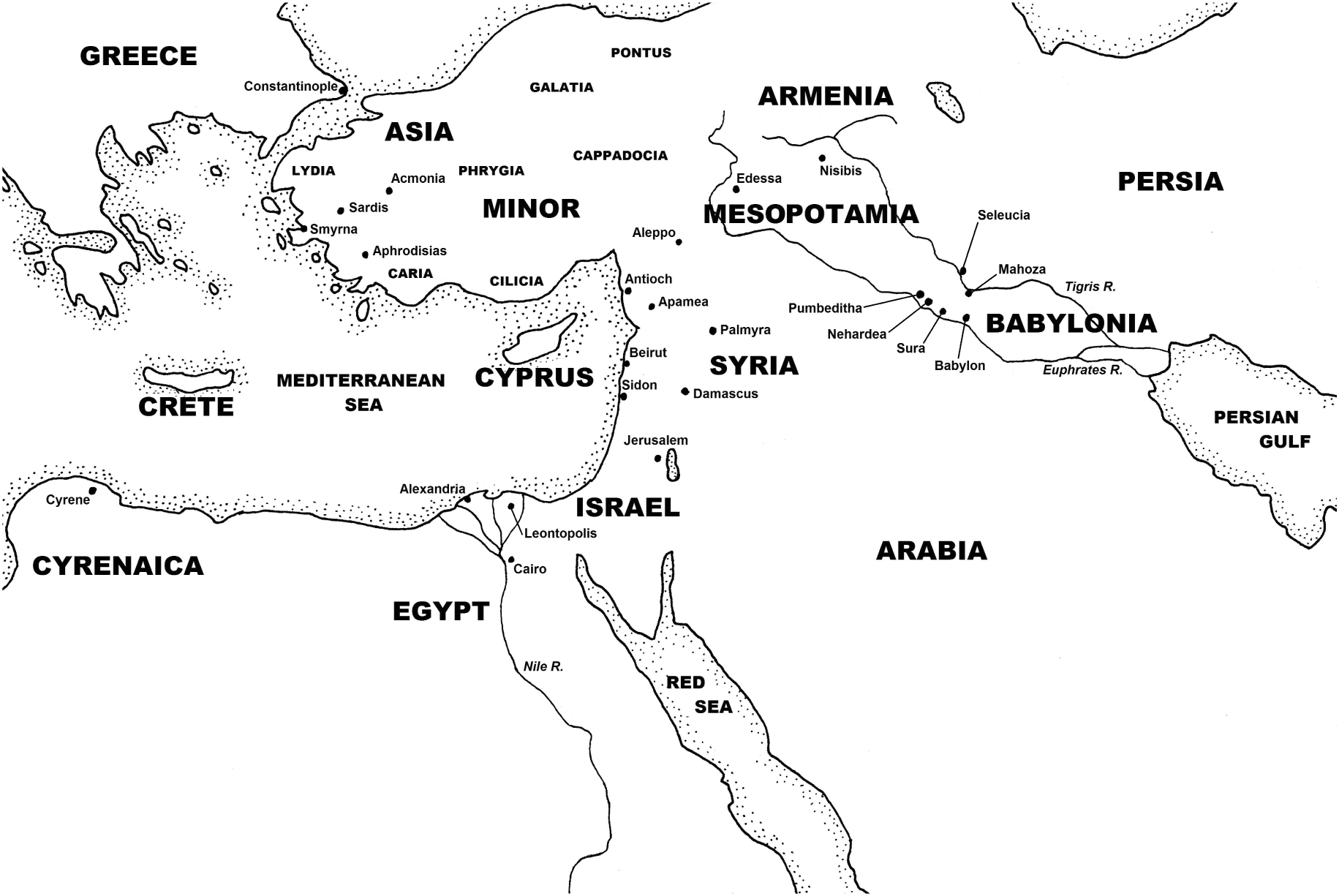

It is my hope that readers interested in the relationship between Jewish, Christian, and pagan literature and culture in late antiquity will be drawn to this book. The book is concerned with narratives that traveled from one culture to another, and how the meaning of these narratives changed from one literary and cultural context to another. These narratives are often very strange to the uninitiated ear; this preface therefore attempts to define fundamental technical terminology and to locate the discussion geographically and chronologically (see the map).

This book focuses on the Babylonian Talmud (or Bavli), composed by rabbis who flourished under Sasanian Persian domination (ca. 224651 C.E. ). These rabbis lived between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, in what corresponds to modern-day southwest Iraq, between the third and sixth or seventh centuries C.E. While two Talmuds survived from late antiquity (see below), the Bavli is the primary subject of this study.

The rabbis, primarily on the basis of their knowledge of Torah, competed with other groups and individuals for authority over the Babylonian Jewish community, although the precise extent of the authority of any of these competing groups is by no means clear. Precisely what the rabbis meant by Torah is a complex question, although it certainly included expertise in traditional rabbinic learning (see below) and scriptural interpretation, as well as a variety of other subjects, such as astrology, dream interpretation, and the ability to control demons.

This book focuses to a lesser extent on the Palestinian Talmud (or Yerushalmi), composed by another major community of rabbis, who flourished in the land of Israel under Roman domination between the second and the late fourth or early fifth centuries C.E. Palestinian rabbis composed other major works that figure in this study (see below), whose relationship to the two Talmuds is a matter of scholarly dispute, but which seem to have been edited during the fifth and sixth centuries C.E.

Throughout this book, the term Tannaim refers to rabbis who flourished in Palestine between the first and the early third centuries C.E. , Some rabbis, for reasons that are not entirely clear, have no honorific preceding their names, notably the prominent third-century Babylonian Amora Shmuel, and other individuals whose rabbinic status is in doubt, notably Hanina ben Dosa, are rabbinized in the Talmud by the addition of the honorific R. introducing their names. If the honorific is well attested in the manuscripts of the Talmuds, we use it in our discussions, intending by it no claims regarding the biography of the individual, but only recognition of an attempt by the classical rabbis to depict a nonrabbi as one of their own.

Some Talmudic material predates the destruction of the second Temple in 70 C.E. , but this material derives from groups or individuals other than rabbis, since the earliest rabbis lived after the destruction of the Temple. Study of second Temple literature, for example, reveals that the Talmud contains a significant amount of pre70 C.E. literature, but the Talmud does not explicitly

We will also refer to anonymous editors of the material preserved in both Talmuds. Some scholars claim that the anonymous material comprises the latest stratum of the Talmuds, while other scholars claim that it was produced contemporaneously with the material produced by the Amoraim. Throughout this book I make every effort to avoid taking a stand on this issue in the absence of concrete proof, since in my opinion, scholars too often base conclusions about the chronology of the text based on preconceived notions regarding the provenance of the anonymous material. Very often we will be able to assert responsibly only that the anonymous material postdates the latest Amoraic material in a given text.

The past half century or so of research, furthermore, has provided abundant evidence that attributions of statements to particular rabbis are often not trustworthy, hampering our efforts to date or locate even the attributed material. Throughout this book I make no assumptions about the chronology and geography of isolated attributed statements, since I take very seriously the possibility of pseudepigraphic attribution. Only if a statement conforms to well-documented patterns exhibited by rabbis known to have lived during the approximate time and place as the author of the statement do I tentatively assume that it is possible to draw chronological and geographical conclusions. As I noted in an earlier study,

It is frequently possible to divide the Talmud into its constituent layers and reach significant conclusions about the literature, personalities, and institutions of the rabbis who flourished prior to the Talmuds final redaction. Material attributed to early rabbis often differs from that attributed to later rabbis; early material is at times even antithetical to the standards and norms of later generations.

Even when we have this much proof of the layered nature of the Talmud, however, we must remain cognizant of the relatively fragile basis upon which our chronological and geographical conclusions rest, since these conclusions depend primarily on the internal evidence of the Talmuds, and only in rare instances on the chronology and geography of events documented in sources external to the Talmuds. Geonic chronicles sometimes provide a measure of confirmation of the internal Talmudic evidence. The historical value of the geonic chronicles is enhanced by the fact that the information in these works appears to be based in part upon authentic traditions deriving from earlier sources.