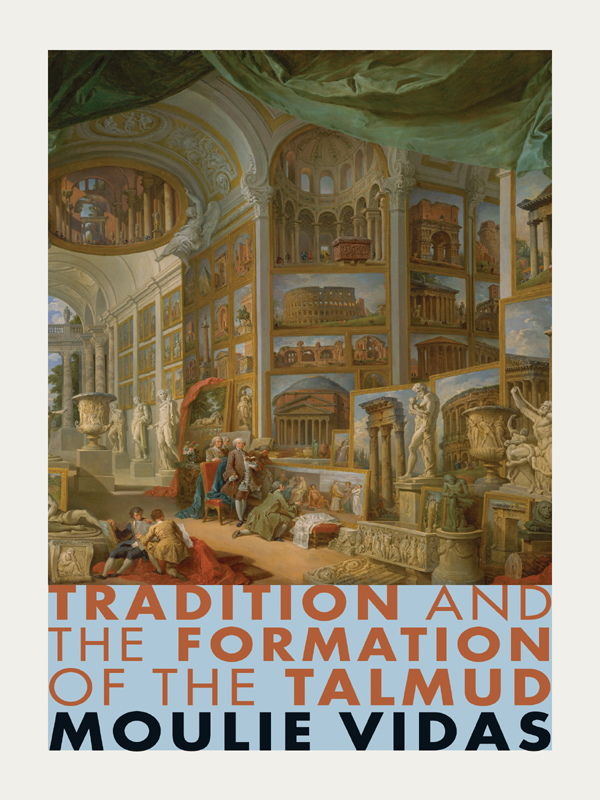

TRADITION AND THE FORMATION OF THE TALMUD

TRADITION AND THE FORMATION OF THE TALMUD

Moulie Vidas

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock,

Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, Ancient Rome, 1757. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gwynne Andrews Fund, 1952 (52.63.1). Image The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vidas, Moulie, 1983 author.

Tradition and the formation of the Talmud / Moulie Vidas.

pages cm

Based on a thesis (Ph. D) Princeton University, 2009.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15486-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)1. TalmudHistory.2. Jewish lawInterpretation and construction.I. Title.

BM501.V53 2014

296.125066dc23

2013027785

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Charis SIL, Adobe Hebrew, and Estrangello Edessa

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

A Note on Style Conventions

Biblical verses are quoted from the New Revised Standard Version, sometimes with modifications that clarify the rabbinic reading of the verses. Biblical book references are in standard abbreviated form (Chicago Manual of Style). Translations from other Hebrew and Aramaic sources are mine unless otherwise noted, but are often adapted from standard translations. Talmudic references appear in abbreviated form according to the SBL Handbook of Style. I used Chanoch Albecks revision and expansion of traditional rabbinic chronology to identify rabbis by generation (Introduction to the Talmud, Babli and Yerushalmi). Talmudic manuscripts were consulted through the Sol and Evelyn Henkind Talmudic Text Databank of the Saul Lieberman Institute of Talmudic Research; references to manuscripts rely on versions and identifications in that database.

TRADITION AND THE FORMATION OF THE TALMUD

INTRODUCTION

The Babylonian Talmud (or Bavli), which was produced in the Jewish academies of sixth- and seventh-century Mesopotamia, is a composite document that proceeds by reproducing earlier literary traditions and placing them within anonymous discursive frameworks. This book concerns the relationship between the creators of the Talmud and these traditions.

For a long time, the Talmud was seen as a conservative storehouse of its traditions, but in the past few decades scholars have recognized the creativity that went into its compilation. Still, even recent accounts of the Talmuds formation understand this creativity in terms of continuity with tradition. The scholars who shaped the Talmud, according to these accounts, creatively revised or interpreted traditions to fit new ideas and contexts, but they did so precisely because they made no distinctions between themselves and the material they received; alternatively, these scholars were aware that their interpretation of tradition was innovative, but saw in it the restoration or recovery of lost meaning. In contrast with these accounts, this book argues that a discontinuity with tradition and the past is central to the Talmuds literary design and to the self-conception of its creators.

The tradition in the title of this book refers to the body of received literary materialdicta, teachings, exegetical comments, etc.which is identified and represented in the Talmud as received material. There are, to be sure, other ways in which we can speak of tradition in the Talmud: in its literary practice, the Talmud continues a tradition of composition that is evident in earlier rabbinic documents; the Talmuds imagery and ideas are drawn from a broad Jewish tradition that goes back many centuries; some traditional textual materialespecially terms, formulations, and structureshad a considerable role in shaping the Talmud, but the Talmuds creators embed this material in their composition rather than quote it, not marking it as received from other sources. One cannot speak of the Talmuds literary formation without touching on these matters, but they are not the subject of this book.

My discussion of tradition here centers on the ways in which the designation of something as traditional can be used to invoke discontinuity. We can say, for example, of a certain style that it is traditional in order to contrast it with contemporary, and whether we use this contrast to praise or condemn, we indicate with it that the traditional style is no longer contemporary, that there is a difference between that which belongs strictly to the present and that which we received from the past. A similar function of marking something as traditional occurs in some religious, legal, and philosophical traditions that distinguish between different kinds of justifications and commitments: in some Talmudic passages, for example, justification that appeals to tradition is distinguished from justification that appeals to reason or logical deduction. This use of tradition contrasts what our own reason guides us to do or think with what tradition guides us to do or think. In both of these contrasts, the one between the past and the present and the one between reason and tradition, we posit a gap between us and what is termed tradition: this is traditional rather than contemporary because our style has changed; this is based on tradition and not on reason because we would have acted differently if it were not for tradition.

The first part of this book proposes that this alterity of tradition is central to the Bavlis literary design. The Talmuds creators employ a variety of compositional techniques to create a distance between themselves and the traditions they quote, highlight the contrast between themselves and these traditions, and present these traditions as the product of personal motives of past authorities. While they remain authoritative and binding, these traditions claim to enduring validity is significantly undermined; they are fossilized and contained in the past, estranged from the Talmuds audience. The second part of the book argues that the Talmuds creators defined themselves in opposition to those who focused on the transmission of tradition, and that the opposition and hierarchy they created between scholars and transmitters allows us both to understand better the way they conceived of their project as well as to see this project as part of a debate about sacred texts within the Jewish community and more broadly in late ancient Mesopotamia.

THE CURRENT VIEW OF THE TALMUDS AUTHORSHIP AND ITS INTELLECTUAL ORIGINS

Scholarship from the second half of the twentieth century on has concentrated on the literary artifice of the Talmuds redactors or creators, replacing the model by which the Talmud was seen as a thesaurus faithfully conserving the traditions of the Tannaitic and Amoraic periods.

The literary activities that scholars now attribute to these later sages include the composition of the stamthe anonymous, discursive, interpretive layer of the Talmud; the shaping of the sugyot (sing. sugya)the discourses or essays that constitute the Talmud; the adaptation and transformation of various Tannaitic and Amoraic sources embedded in the Talmud; and, in some cases, the composition of Talmudic stories.

While the image of the Talmuds creators that emerged from these studies was of great innovators of striking originality, scholars have explained this creativity in terms of continuity with tradition. According to David Weiss Halivni, the Talmuds authors, or Stammaim (as he calls them), received their traditions in apodictic form, without reasoning or justification. They then reproduced what they received faithfully, and composed the anonymous layer in order to justify these traditions. Their enterprise is thus innovative in the sense that for the first time the reasoning of tradition was put into literary form, but it is essentially a reconstructive enterprise, whereby the later generation recovers lost meaning and justifies its heritage.

Next page