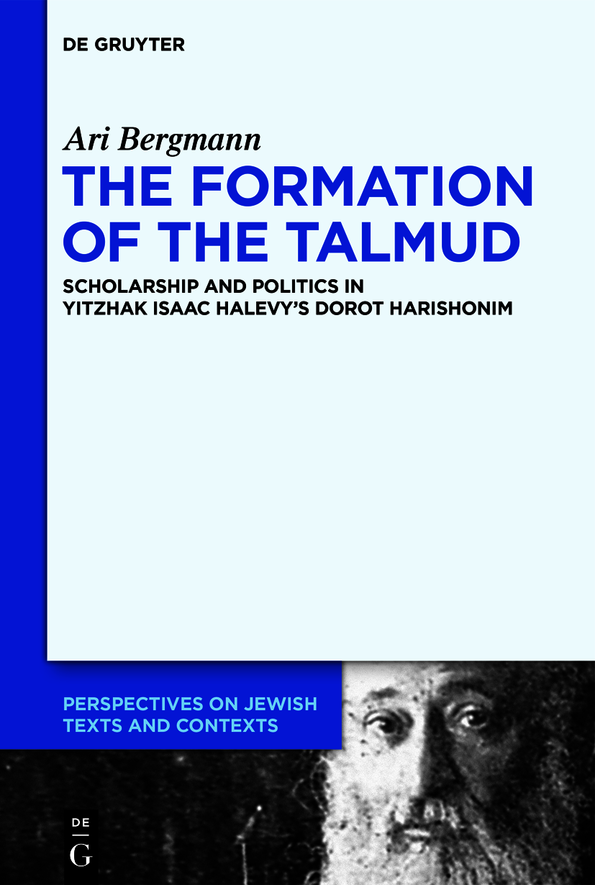

Perspectives on Jewish Texts and Contexts

Edited by

Vivian Liska

Robert Alter

Steven E. Aschheim

Richard I. Cohen

Mark H. Gelber

Moshe Halbertal

Christine Hayes

Moshe Idel

Samuel Moyn

Ada Rapoport-Albert

Alvin Rosenfeld

David Ruderman

Bernd Witte

Volume

ISBN 9783110709452

e-ISBN (PDF) 9783110709834

e-ISBN (EPUB) 9783110709964

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2021 Ari Bergmann, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Oi, Oi, amar Rava, amar Abbaye

Thus Rava said, and thus Abbaye taught

(Backward and forward swaying he repeats

With ceaseless sing-song the undying words).

Is this the smithy, then; is the anvil

Where a peoples soul is forged? Is this the source

From which the life-blood of a people flows,

To feed the generations yet unborn,

And knit the thews of heroes yet to come?

Hayyim Nahman Bialik, Hamatmid (translated by Maurice Samuel)

For Iona

Foreword

It is impossible to overstate the centrality of the Babylonian Talmud to the formation of Jewish religious thought and practice. While the classical Jewish library is massive, no text has shaped the tradition like the Babylonian Talmud. And yet, as has been noted by many scholars, the Babylonian Talmud while attributing statements to hundreds of scholars (rabbis) who span at least the first six Christian centuries has no discernible authorial voice, no obvious point of origin. It speaks from everywhere and anywhere, but nowhere in particular; to all time, but from no time. It is almost as if those responsible for its emergence anticipated the historicist impulse of the modern academic world and said we shall thwart your every effort to understand the history of this collection of material.

For this reason, I long ago came to the conclusion that a definitive history of the emergence of the Babylonian Talmud cannot be written, at least not without time travel. But even for those who might agree with that, the form and structure of Talmudic discourse present so many tantalizing clues that desisting from the effort to unravel the mysteries of the Babylonian Talmuds emergence is impossible for the curious. Further, the many references to specific historical moments, whether to the lives of individual rabbinic figures, or to the political events of the surrounding environment, could not be ignored by those who wish to understand this most elusive of documents.

Thus, for the better part of the last two centuries, scholars have presented their thoughts on the emergence of the Babylonian Talmud. Of course, pre-modern scholars were interested in where this text (among others) came from and who the named rabbis in the text were. But this interest tended to produce chain of tradition chronicles that were designed to buttress claims of unbroken tradition going back to antiquity and/or authority claims for their contemporary institution(s). Yet other pre-modern scholars noticed the formal and structural elements that provide evidence of the history of the Babylonian Talmud; but such scholars tended to engage with them in response to a local interpretive need that is, to the extent that engaging with historical questions might illuminate a specific passage of the Talmud. What neither type of scholar produced is a synthetic history that describes how the Babylonian Talmud in its entirety came to be. They had neither the historical consciousness nor religious interest to take on such a project.

This changes in the nineteenth century, for a range of reasons, many of which are discussed in the pages that await you. Scholars those with university educations, and auto-didacts as well began to knit together the scattered historical claims spread throughout the Babylonian Talmud. They take note of the fact that the Talmud consists of (usually short) statements attributed to specific individuals, generally in Hebrew, and extensive anonymous discussion of these statements, nearly always in Aramaic. How do these parts relate to one another? Is the anonymous layer contemporaneous (or nearly so) with the attributed statements it discusses, and often modifies? Is it much later? Recent scholarship, especially that of David Weiss Halivni and Shamma Friedman and their students, argues forcefully in favor of the latter. But there remain passages that seem to support the former. The latter position revolutionizes the way we understand how the Babylonian Talmud speaks, and raises an urgent set of historical questions: If the anonymous layer is later, when and why does it emerge? When did it end? In short, when was there a Babylonian Talmud?

Such questions were rarely of concern to the most traditional of Jews, those who, since the middle of the nineteenth century, have come to be called Orthodox. This is especially true of those who came out of the Eastern European yeshivah world. While methodologically innovative in their analytical approach to the text, they were untroubled by the historical questions that engaged the academics.

Perhaps the most important exception was Yitzchak Isaac Halevy (Rabinowitz; 18471914), a youthful prodigy who came to study at the famed Volozhin yeshiva at the age of 13, going on to become a member of the staff there. He eventually found his way to Germany and there took on a massive project to write the history of the rabbinic tradition, designed, among other things, to rebut theories of scholars like Nachman Krochmal, Heinrich Graetz, and Isaac Hirsch Weiss that were anathema to the Orthodox community. Because his work was generally treated as little more than Orthodox apologetics, Halevys influence on academic scholarship has been minimal. To the extent that historians of modern European Jewish life attended to him at all, it was generally to focus on his role in establishing the important Agudath Israel, an international organization created to advance the cause of Orthodox Judaism.

It is the signal contribution of Ari Bergmann to demand that the academic community take another look. While one cannot deny the strong apologetic tendencies in Halevys opus (and he doesnt), Bergmann shows that Halevys narration of the emergence of the Babylonian Talmud flawed though it is must be taken seriously, not only as an important Orthodox stake in the ground, but also as one of the most elaborate and detailed accounts ever written on this topic. Bergmann, a student of Halivni, painstakingly reconstructs Halevys arguments, evaluates their strengths and weaknesses, situates them in their historical and political contexts, and provides his reader with a deeper understanding of the recondite nature of the whole question. The Babylonian Talmud stubbornly holds on to some of its mysteries, but the reader of Bergmanns work will come away with a new understanding of the current state of the question, as well as the role that ideology and politics have played in the development of the discussion. For that Bergmann has earned our gratitude.

Jay M. Harris, Harvard University

Acknowledgments

This book is the result of an exhilarating journey on which I encountered, and benefitted from the contributions of, many extraordinary people. It would not have reached its destination if not for the guidance, encouragement, feedback, and advice of so many outstanding mentors, colleagues, and friends.