Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2022 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

and

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE, UK

Copyright 2022 Andrew Sangster

Hardback Edition: ISBN 978-1-63624-178-4

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-63624-179-1

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ Books

Typeset in India by Lapiz Digital Services, Chennai.

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131

Fax (610) 853-9146

Email: casemate@casematepublishers.com

www.casematepublishers.com

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249

Email: casemate-uk@casematepublishers.co.uk

www.casematepublishers.co.uk

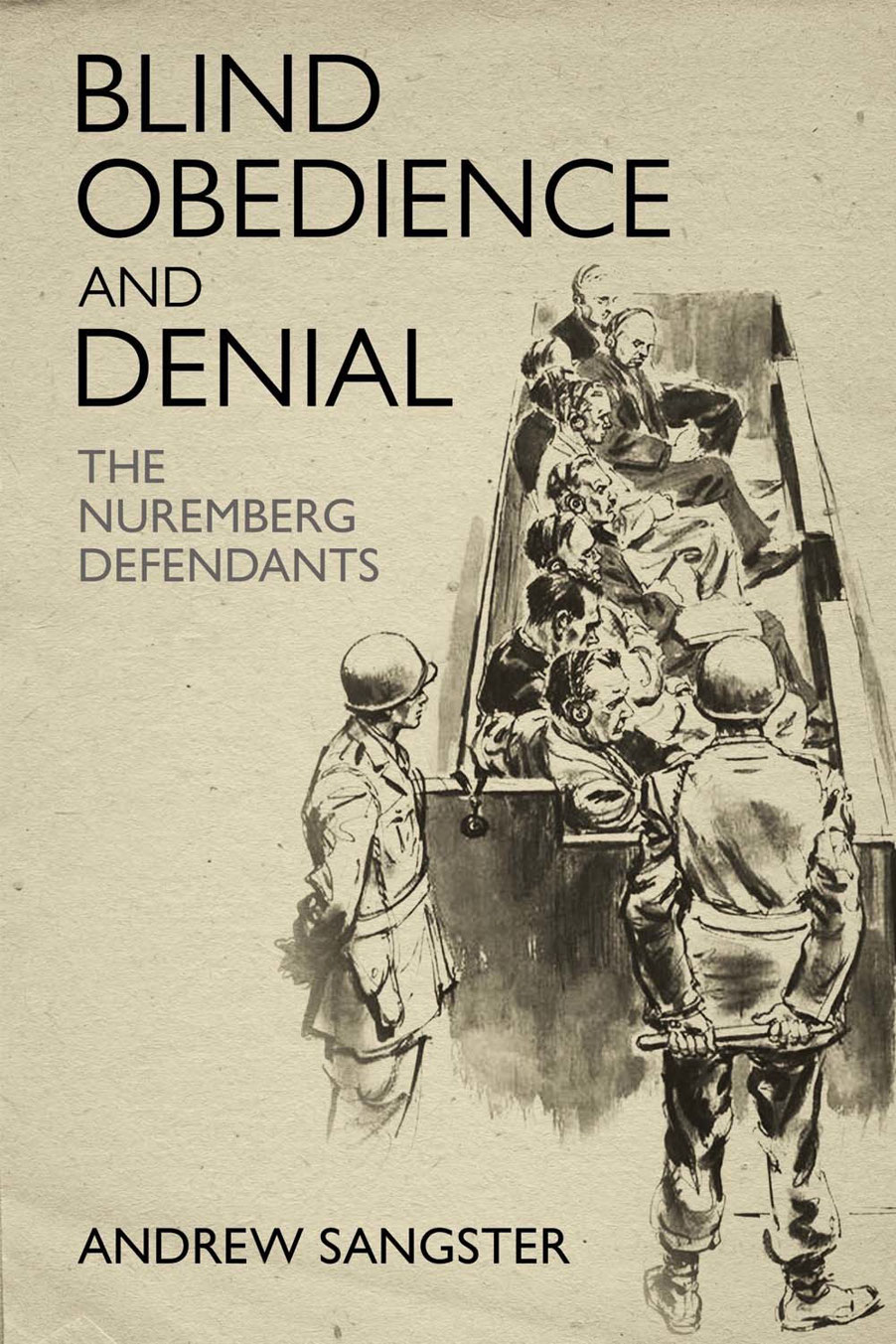

Cover image (also on page xiii): Second row of defendants, including Gring, Hess, von Ribbentrop, and Keitel, created by Edward Vebell, illustrator and US soldier. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of Sheila C. Johnson)

Contents

Foreword

Andrew Sangster has done a great service to the historical community in his study of the defendants at the Nuremberg Trials. By examining these men, their motivations and stories and legal defences, he is addressing the essential but often evaded subject of morality in history. Given that all nations and their armies commit atrocities in warfare, on what basis could the Allies try their defeated enemies for their crimes? Are present-day historians and their readers in any better position to pass judgement?

Certainly in our own present climate, there is no lack of public appetite for revising the historical record in connection with slavery and taking direct action against memorials to those associated with slavery and racism. Historians, for their part, tend to be reluctant to take on the role of overt moral arbiters. They see their role as recording what happened and why. Dr Sangster, however, is reminding us that all historical actors make moral and immoral choices; at Nuremberg, the victorious Allies took the unusual step of making the leading Nazis accountable for those choices in a court of law.

The Allies were conscious of their own vulnerability to accusations of having also committed atrocities in war. They were motivated in part, however, by their consciousness of the need for more rigorous standards of behaviour in war, particularly given the availability of new weapons of mass destruction. They were also determined that one uniquely egregious crime the attempted extermination of European Jewry by industrial methods should not go unrecognised or unpunished.

Politicians and opinion shapers often indulge in the rhetoric of learning the lessons of history in order that such crimes should never happen again. Human beings, however, remain stubbornly true to nature and continue to engage in war on false pretences, to commit atrocities on and off the battlefield, and to turn a blind eye to offences committed by political and strategic partners. What is different in the early 21st century, however, is the continuing erosion of any agreed basis of morality, even among the Western democracies.

At the end of World War II, that ethical basis was still securely to be found in the Bible as an expression of the Judaeo-Christian tradition. In 1946, Franois de Menthon, the prosecutor representing republican, secular France, could still publicly appeal to the Scriptures as providing an agreed standard for human action. The Nuremberg judgements could not have been made without an assumption of the inviolable dignity of every human person.

Today, while that tradition retains a residual presence, it is now for most people unconnected to any sense of religious belonging or practice. If the sanctity of human life or of the individual person is no longer an accepted moral norm, what are the chances of survival for a Western civilisation founded on that assumption? This history of the Nuremberg Trials reminds us of the cost of the Nazis rejection of that standard.

The Revd Canon Dr Peter Doll

Preface

On 17 January 1946, Franois de Menthon closed the French case at the Nuremberg Trial of Nazi war criminals with these words:

Who can say: I have a clean conscience; I am without fault? To use different weights and measures is abhorred by God If this criminality had been accidental; if Germany had been forced into war, if war crimes had been committed only in the excitement of combat, we might question ourselves in the light of the Scriptures. But the war was prepared and deliberated long in advance, and upon the very last day it would have been easy to avoid it without sacrificing any of the legitimate interests of the German people. The atrocities were perpetrated during the war, not under the influence of a mad passion nor of a warlike anger not of an avenging resentment, but as a result of cold calculation, of perfectly conscious methods, of a pre-existing doctrine.

When these words were re-read years later, many asked why the French prosecutor made no mention of what later became known as the Holocaust.* One suggested reason was that it was more of an Eastern European issue, another that it may have been an embarrassment at Vichy Frances anti-Semitic stance, and perhaps this was true for most European nations. Nevertheless, de Menthons closing words clearly outlined why the trial was taking place. During the war, both sides committed atrocities. Individual soldiers, commanding officers, and governments were behind some appalling decisions from the legal and, above all, the moral perspectives.

The Nazi regime had demonstrably planned not only an aggressive war but ordered the vilest atrocities in living memory. The extermination of Jewish people and many others exposed by films and survivors appeared to come as a disturbing shock to some of the defendants, and most pretended ignorance. But all the evil reflected in the indictments demanded that the Nazi regime had to be held to account, not least in the hope it would never happen again.

The International Military Tribunal (IMT) was an indictment of the Nazi regime with the defendants being selected as senior representatives. This exploration paints a brief backdrop to the trial but concentrates on the individuals in the dock. This book explores who and what sort of people they were as individuals, and why they had made their decisions to support a regime which brought untold suffering on the world. An estimated 80 per cent of this study is given to the selected culprits some better known than others, some more infamous in their reputations and explores how and why they were condemned on the international stage.

There were many complex issues as far as the prosecuting countries were concerned, but four issues tended to dominate the minds of the defendants. The first, especially for the military, was the argument you were just as guilty as us, namely the banned tu quoque (you also did the same) argument. This enveloped the second argument that the trial was hypocritical, not least with Joseph Stalins cohorts sitting in judgement. The third area was obeying orders, which also related to the tu quoque theme as all sides had obeyed questionable orders.

Next page