PREFACE.

THE purpose of an historical introduction to these volumes is, chiefly, to present a narrative of public events which would dispense with frequent repetitions in the histories of the separate towns constituting the county, and thus secure a unity otherwise unattainable. For this design a general outline of the colonial history of Massachusetts was found to be indispensable.

No history of Middlesex could be written that did not largely embody the annals of Charlestown, the parent of all the towns of the county; the important part has, therefore, been related in the introduction, instead of in a separate article.

The history of Brighton, which so long formed a constituent part of the county, was also deemed essential to the general completeness of the work, more especially as the municipality has no separate written history of its own.

Deeming such a course not only equitable, but for the interests of historic truth, the authors of the articles in this work have freely expressed their own views upon controverted questions, but the editor accepts the responsibility only for what is embraced in the introductory chapters.

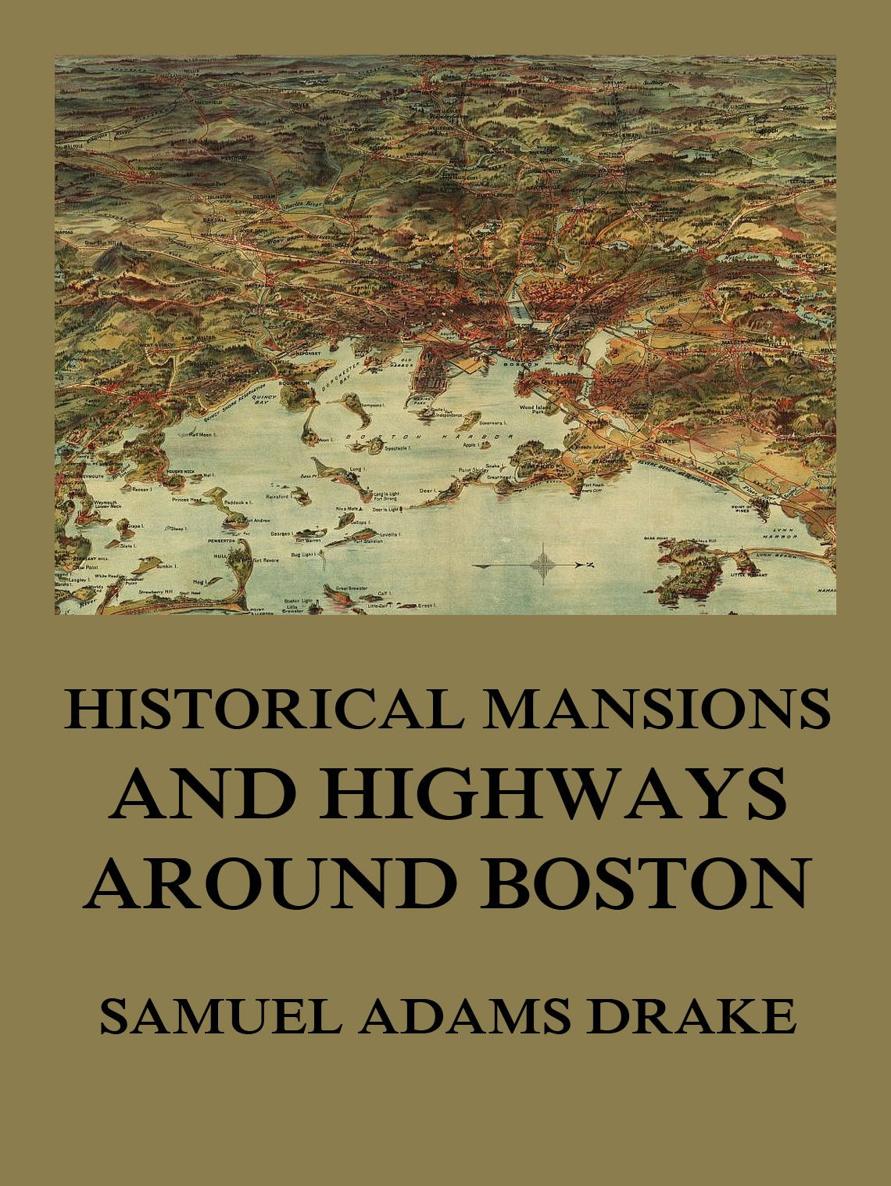

SAMUEL ADAMS DRAKE.

Melrose, August 20, 1879.

I. THE MASSACHUSETTS COMPANY.

It is not often that so small a political division as a county obtains a history of national significance. For us, the explanation is easy. In New England there is no difference of race, language, or religion to perpetuate distinctions. The county is usually regarded as a convenient subdivision of the territory of a state for the ordinary purposes of government, nothing more. Accident, and accident alone, may have made the ground historic. Family traditions may do something; but it is only in a few instances that a sentimental attachment can be founded on them. The state claims the citizen; the citizen, the state.

But it has happened in the State of Massachusetts that the counties of Plymouth, Essex, and Middlesex, instead of being merely the expansion from a common center of population, were originally distinct political communities, and have, therefore, to some extent, a separate history of their own. Plymouth was a separate colony and government until the accession of William III.

Essex witnessed the laying of the foundations for the colony of Massachusetts Bay; Middlesex, the formal assumption of government, under the royal charter, by men who brought with them to the New World the germ of an independent state.

Thus, these three communities indicate three historic eras. Not merely accidental collections of adventurers, they are the embodiment of great principles which in time became the ruling ideas of a nation.

To New England they indicate not only the boundary between barbarism and civilization, but the centers from which most of her native-born population is derived. In so far as great events may illustrate a history, Middlesex surpasses her sisterhood of original shires. So much is hers of right to claim. It concerns us that the justice of this claim shall lose nothing by our presentation of it.

The History of Middlesex is so interwoven with that of the colony, province, and commonwealth, that it is indispensable to a correct understanding of the relation it bears to each, the causes which led to the settlements of 1628 and 1630, and the principles that animated the settlers, to review such portions of the common history as may guide to an intelligent opinion of the movement which resulted in establishing a second English colony in Massachusetts Bay. It is inseparable from the fact that the settlement of 1630 began upon territory of which the county was subsequently formed, and because the first church, the first formal act of government, were instituted and enacted there. A simple recital of what history has preserved of the principles and acts of the founders of the colony seems, therefore, the appropriate introduction to our subject.

We do not consider it needful to recapitulate the various attempts, successful or unsuccessful, to colonize New England. A knowledge of them is not essential to our present purpose. The founding of the colony of Massachusetts Bay constitutes a distinct and compact chapter of American history, having little or no relation to other attempts except in so far as they directed men's eyes and thoughts to New England when the time was ripe for a more vigorous and more prosperous undertaking. Already a little band of religious exiles had planted themselves in a corner of the Bay, and, by exercising the most heroic fortitude, history records, founded the colony of Plymouth. In point of time, in point of heroism, in respect of aims, civil and religious, that immortal little community takes precedence of every other; and it must ever continue to command the unbounded admiration and respect of posterity.

Plymouth Colony had been in existence four years, and had given such assurance of its ability to sustain itself as to embolden some gentlemen of the West of England to attempt beginning a plantation at Cape Aim. In 1624, these persons formed a joint stock association known as the Dorchester Company, and sent over a number of emigrants to begin the work of planting and fishing, and to prepare the way for those that might come after them. The Rev. John White, a Puritan minister of Dorchester, England, appears prominently as one of the promoters of this enterprise, of which he doubtless considered himself the father. So far as the evidence goes, the Dorchester Company had no other motive than gain. By a permanent settlement they facilitated the fishery and increased its profits.

The handful of settlers at Cape Ann were joined the next year by Roger Conant, a "pious, sober, and prudent gentleman," and by John Lyford, a minister, both of whom had left Plymouth and were then living at Nantasket. Conant was appointed governor of the plantation at Cape Ann, and Lyford was invited to be its minister. Notwithstanding the excellent character given of him, Conant was unable to repress the insubordination of the lawless men sent over by the Company; while the Company, discouraged by heavy losses, very soon determined to sell their ships and abandon the enterprise. They offered a free passage home to England to such as wished to return; but Conant and a few others, upon the assurance of Mr. White that he would procure them a patent and send them men and provisions, decided to remain. Meanwhile, not liking their situation on the sterile cape, Conant and his men removed to Naumkeag, now Salem, where they cleared land, built houses, and awaited the fulfilment of the promise of efficient help. And this was the state of affairs at Naumkeag in 1626.

During the years 1626 and 1627 a movement for planting another colony in Massachusetts Bay was freshly agitated and finally matured. It originated, or is believed to have originated, with the Rev. John White, already mentioned, whose aim was to sustain the weak plantation at Cape Ann, which threatened to dissolve unless speedy measures were taken for its relief.

Through the active, unremitting exertions of Mr. White, several gentlemen of Dorchester, or belonging to the neighborhood, purchased of the Council of Plymouth all that part of New England comprised between a point on the coast line three miles north of the Merrimack River and three south of the Charles, and extending westward to the South Sea. All the lesser grants which had from time to time been made within this territory were considered forfeited, or annulled, by the terms of the new session, which was executed the 19th of March 1628. The grantees took the name of the Massachusetts Company.