Source: AMPECA, West African Report, 3 December 1962.

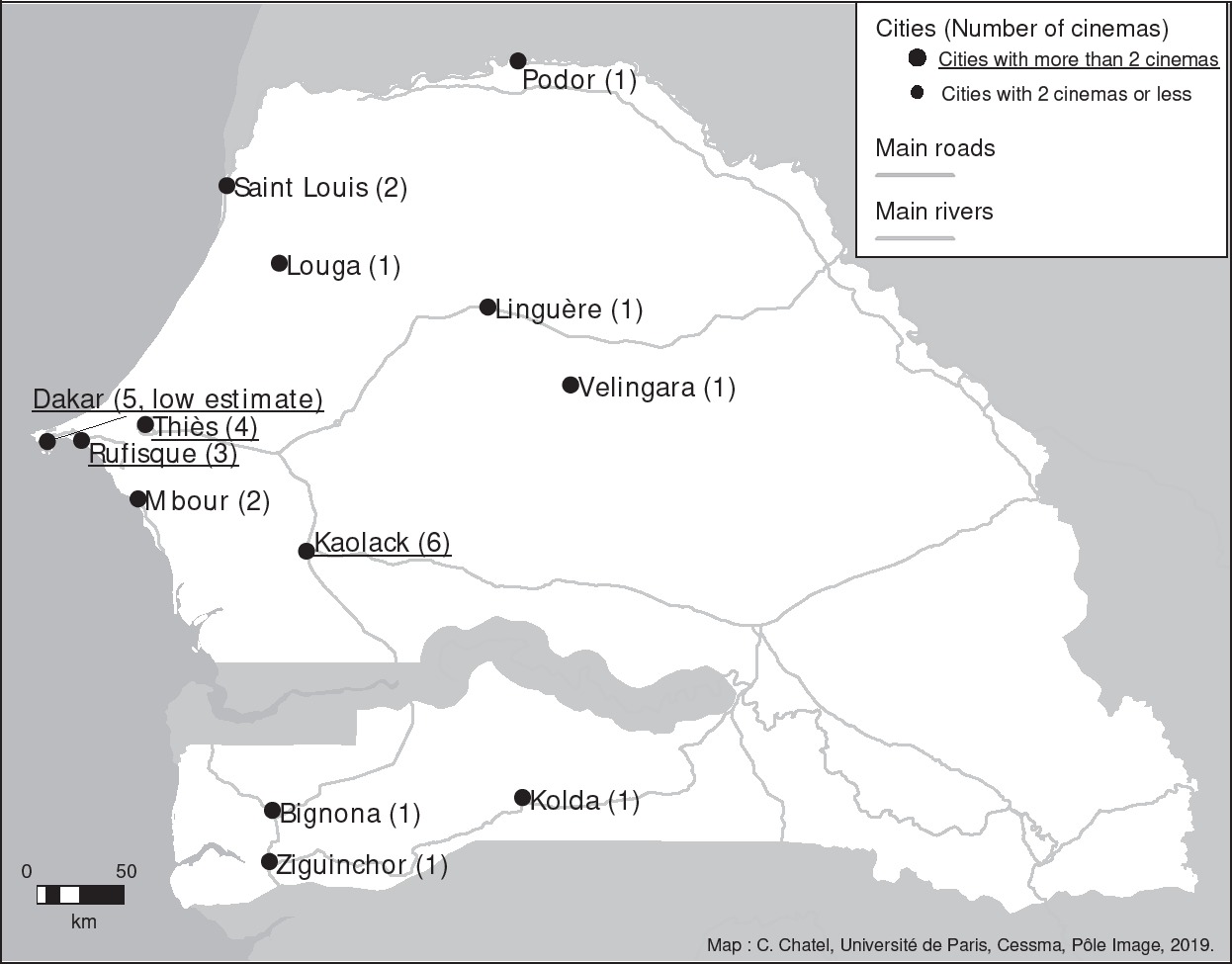

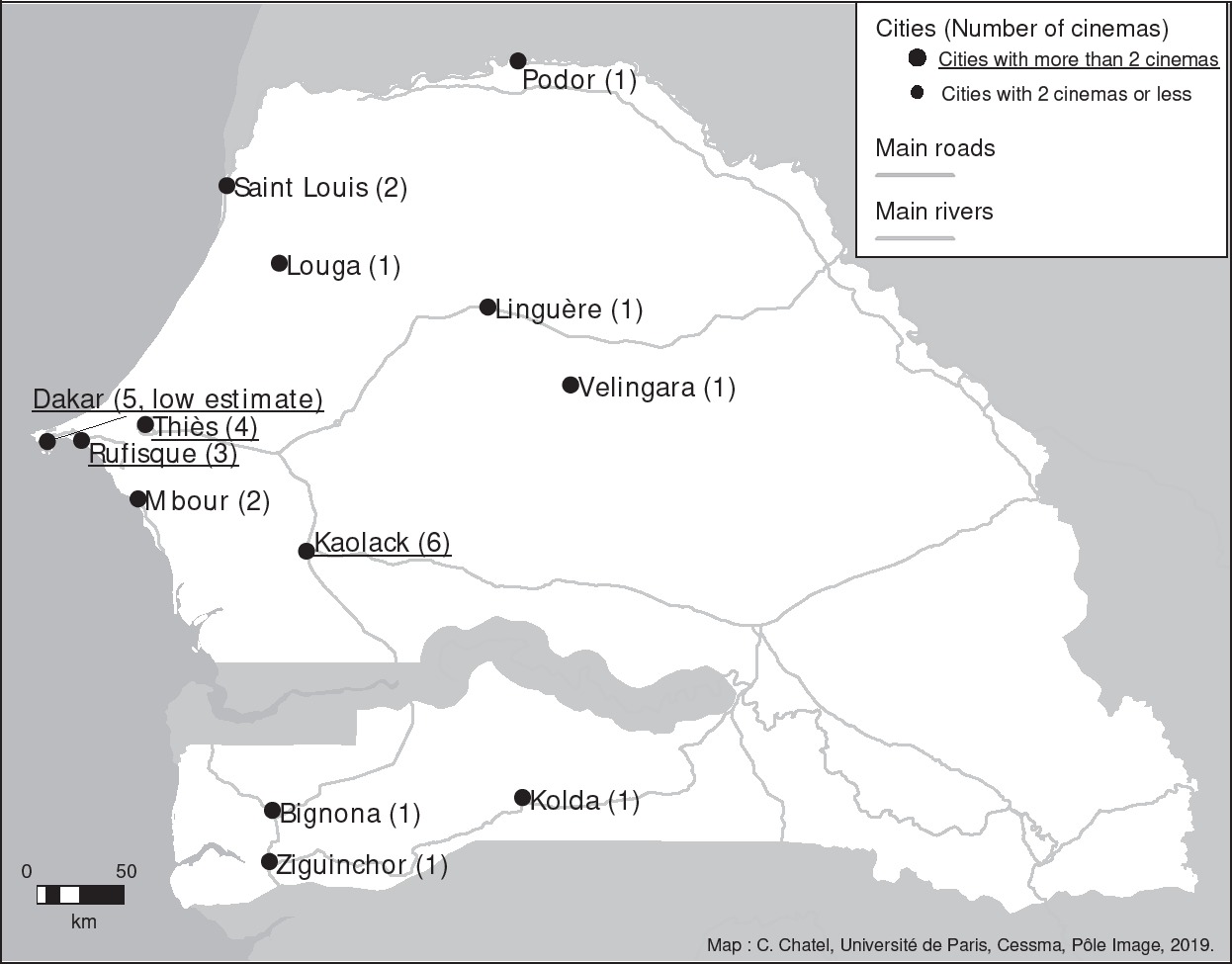

Cinemas in Senegal, around 1958

Source: Guide AOF, 1958 (Les Guides bleus, Afrique de louest, AOF-Togo, Hachette, 1958).

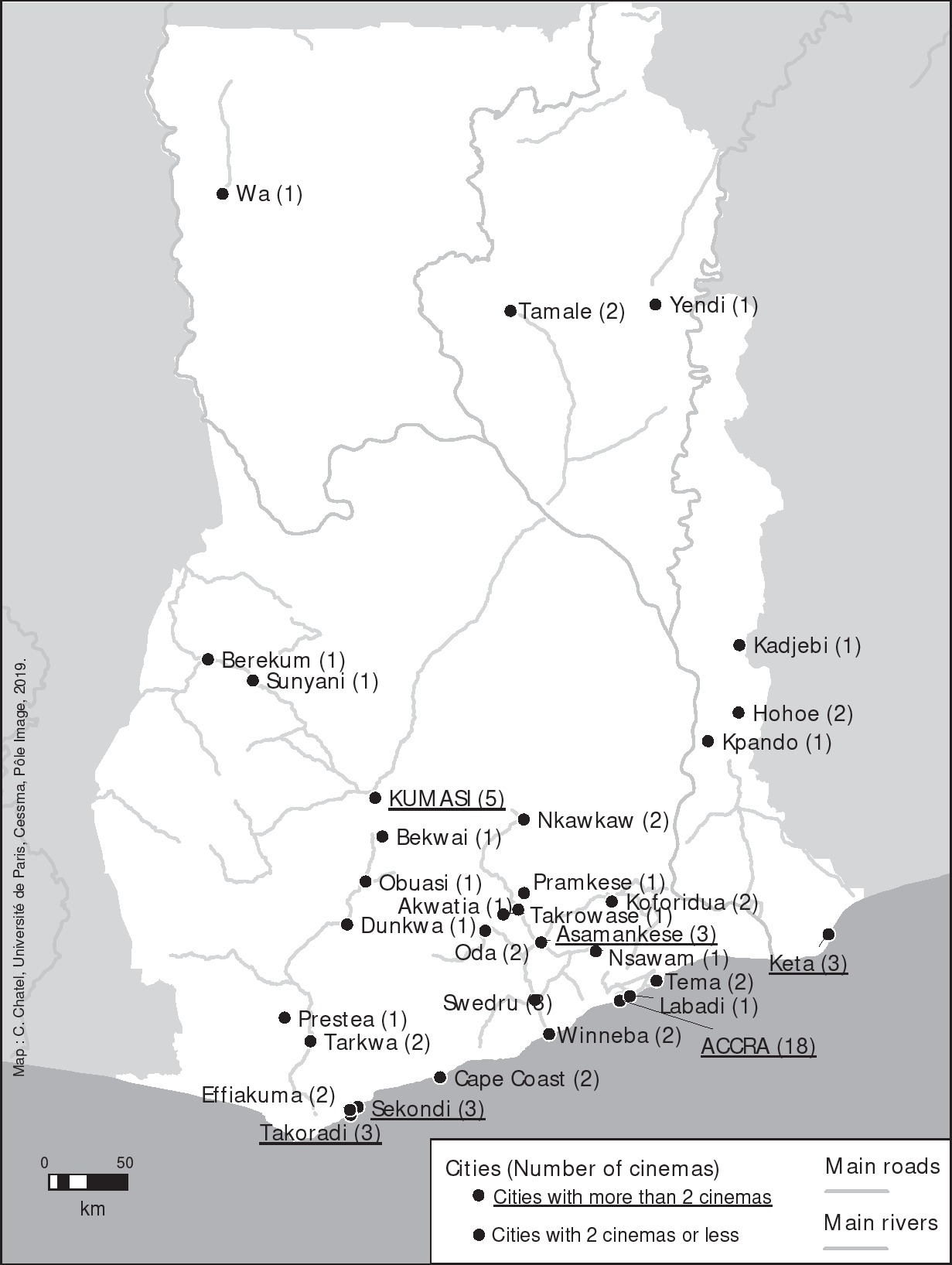

To refer to the countries, I use colonial terms: French Sudan for present day Mali; Gold Coast for Ghana.

| BFI | British Film Institute |

| CFU | Colonial Film Unit (founded in 1939) |

| CO | Colonial Office |

| COMACICO | Compagnie Marocaine Cinmatographique et Commerciale, founded in 1933, then Compagnie Africaine Cinmatographique Industrielle et Commerciale |

| CPP | Convention Peoples Party, Ghana |

| FOM | France dOutre-Mer |

| FWA | French West Africa (also AOF, or Afrique occidentale franaise) |

| NEA | Nouvelles ditions Africaines |

| RDA | Rassemblement Dmocratique Africain (African Democratic Rally) |

| RG | Renseignements gnraux (Intelligence service) |

| SECMA | Socit dExploitation Cinmatographique Africaine (founded in 1936) |

| SFIO | French Socialist Party (Section franaise de lInternationale ouvrire) |

| SLWN | Sierra Leone Weekly News |

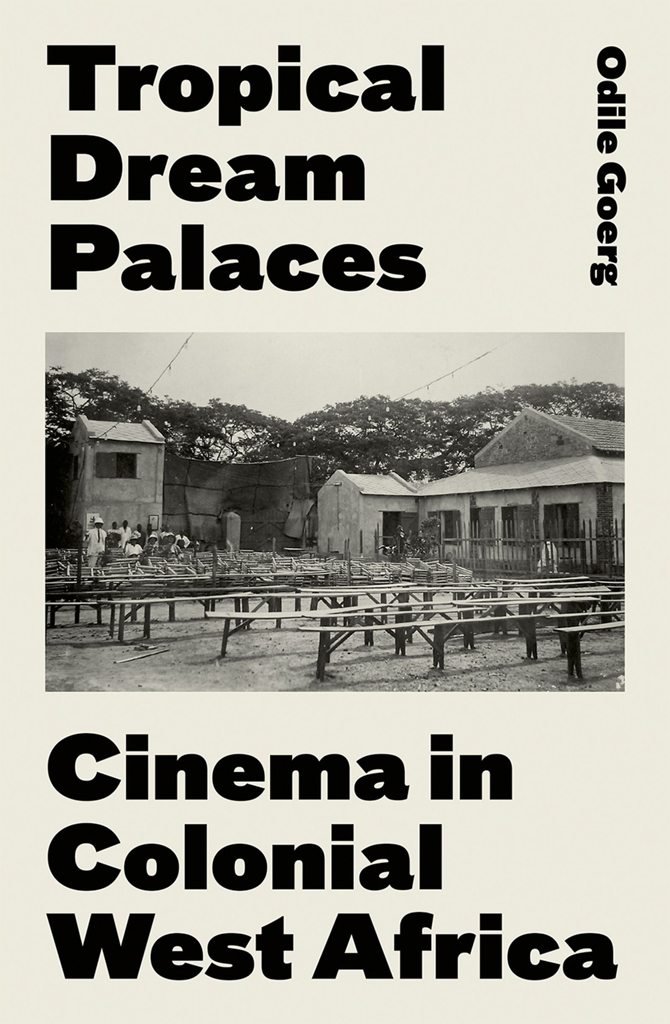

Less than fifty years ago, West Africas towns were full of cinemas, known then as dream palaces. Mobile cinema vans also traversed the countryside. A highly popular urban leisure activityalso popular in rural areas when villagers got the chanceuntil the 1970s to the 1980s, cinema offered spectators a break from their daily routines. Even though not all countries were equally well equipped, the cinema presented images which resonated well beyond the four walls of the movie theatre. Watching a film today, at the start of the twenty-first century, is far easier and often instantaneous thanks to internet streaming and mobile phones, but, as a result, the culture of sharing that accompanied public screenings in Africa has also gone. All that remains is a handful of buildings which have been converted into warehouses or churches, and the nostalgia of those who lived through this period. We just followed the vibe; we didnt know we would be questioned about it, said Soumala Coulibaly, who was a fervent film-lover in the 1950s.

Cinema spread rapidly in Africa. All over this vast continent, just like everywhere else, people were attracted to the novelty of the moving image, to its promise of escape, and to the messages it conveyed. From Zanzibar to Brazzaville, from Johannesburg to Dakar, the first film showings were a huge hit with the initially limited turn-of-the-century audiences. Cinema continued to grow from then on, becoming the predominant urban leisure activity on the eve of Independence.

The chance meeting of cinema and colonization would not have had the same impact without the presence of dynamic local economic actors and enthusiastic spectators. While the demand for images was immediate, supply, on the other hand, was subject to complex processes. This was due to conflict between the entrepreneurial desire to develop a profitable activity on the one hand, and, on the other, the concern of the colonial administration, certain entrepreneurs, and the political and moral elites not to rock local societies by introducing foreign images that risked weakening colonial domination and upsetting social and gender relations and representations of both others and the self. A place of escape, as the expression dream palace illustrates, and a place where spectators awareness could be raised through education, cinema was indeed potentially subversive for populations whom the authorities sought to control, and also offered subjected peoples a breathing space.

It is this history of both expansion and censorship that Tropical Dream Palaces seeks to trace, filling a historiographic void with regard to West Africa, while at the same time looking further afield to Central Africa and its different models. Bar a few exceptions, swathes of the continent indeed remain unstudied in this field, even though cinema took off there actively, albeit at varying rhythms and to different degrees.

Historiographic perspectives

The past few decades have seen the publication of a growing number of works devoted to African cinema created after Independence, or to cinema in Africa. The list is now too long to offer an exhaustive overview, especially as approaches vary according to historiographic trends and time. After the first general studies of films made in Africa by African directorsnotably Le Cinma africain des origines 1973 by Paulin Vieyra (1975), Focus on: African Filmmaking Country by Country by Nancy Schmidt (1985), Le Cinma africain de A Z by Frid Boughedir (1987), and Twenty-Five Black African Filmmakers by Franoise Pfaff (1988)studies have focused on the conditions of the emergence, then the development of these films, placing the emphasis on directors, national productions, film genres, or the ways in which cultures are formed by the representations constructed in these films. Other research has explored distribution mechanisms and institutional aspects, post-Independence state policies, and the development of festivals, notably the FESPACO (Pan-African Festival of Film and Television of Ouagadougou), set up in Ouagadougou in 1969. While incorporating historical reflection, and taking the colonial legacy into account, the existing research does not develop these perspectives further. This reflects the variety of disciplines that focus on cinemafrom anthropology to film studies, communications studies, and cultural studies.