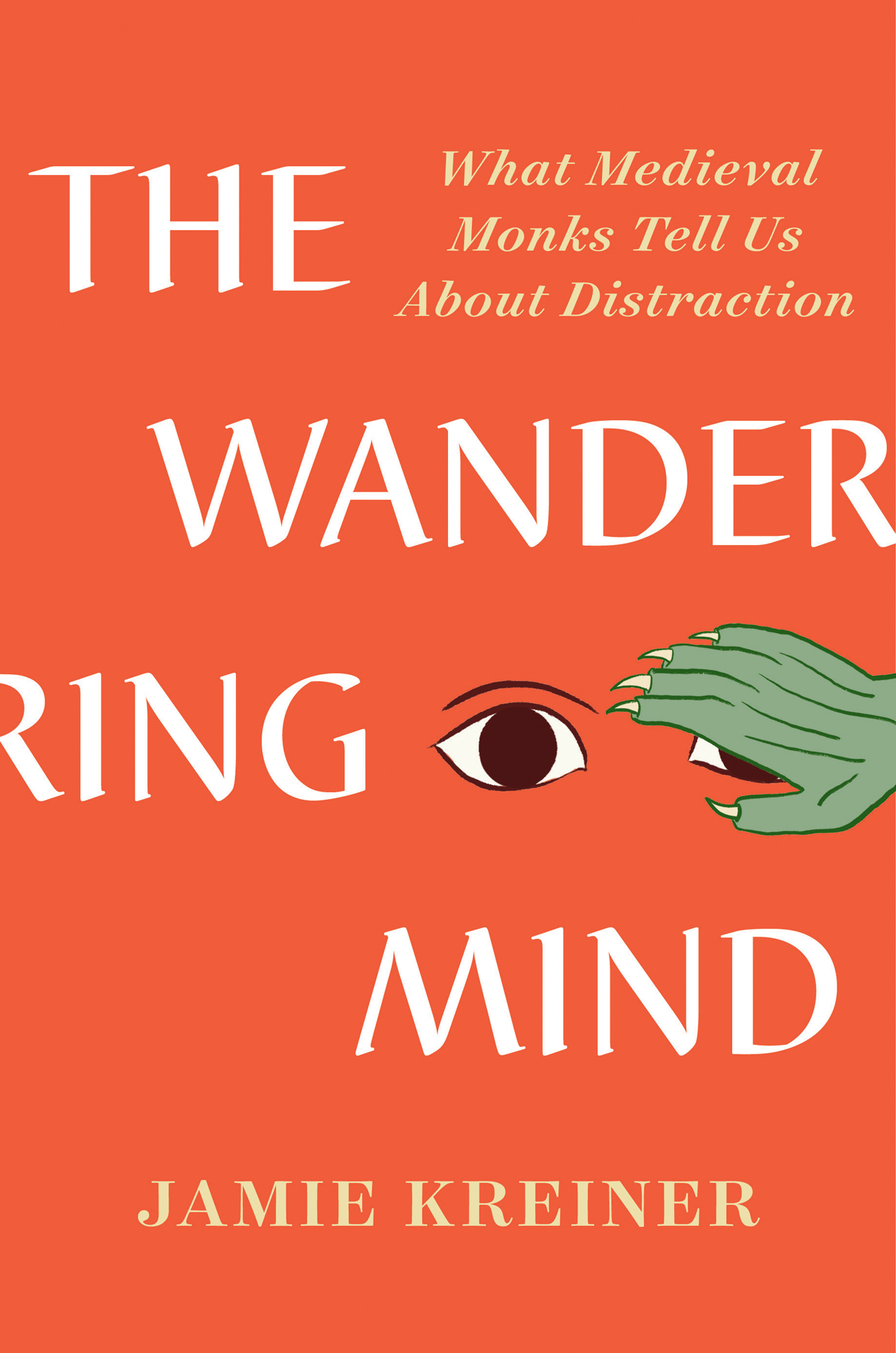

Jamie Kreiner - The Wandering Mind: What Medieval Monks Tell Us About Distraction

Here you can read online Jamie Kreiner - The Wandering Mind: What Medieval Monks Tell Us About Distraction full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2023, publisher: Liveright, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Wandering Mind: What Medieval Monks Tell Us About Distraction

- Author:

- Publisher:Liveright

- Genre:

- Year:2023

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Wandering Mind: What Medieval Monks Tell Us About Distraction: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Wandering Mind: What Medieval Monks Tell Us About Distraction" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A revelatory account of how Christian monks identified distraction as a fundamental challengeand how their efforts to defeat it can inform ours, more than a millennium later.

The digital era is beset by distraction, and it feels like things are only getting worse. At times like these, the distant past beckons as a golden age of attention. We fantasize about escaping our screens. We dream of recapturing the quiet of a world with less noise. We imagine retreating into solitude and singlemindedness, almost like latter-day monks.But although we think of early monks as master concentrators, a life of mindfulness did not, in fact, come to them easily. As historian Jamie Kreiner demonstrates in The Wandering Mind, their attempts to stretch the mind out to Godto continuously contemplate the divine order and its ethical requirementswere all-consuming, and their battles against distraction were never-ending. Delving into the experiences of early Christian monks living in the Middle East, around the Mediterranean, and throughout Europe from 300 to 900 CE, Kreiner shows that these men and women were obsessed with distraction in ways that seem remarkably modern. At the same time, she suggests that our own obsession is remarkably medieval. Ancient Greek and Roman intellectuals had sometimes complained about distraction, but it was early Christian monks who waged an all-out war against it. The stakes could not have been higher: they saw distraction as a matter of life and death.

Even though the world today is vastly different from the world of the early Middle Ages, we can still learn something about our own distractedness by looking closely at monks strenuous efforts to concentrate. Drawing on a trove of sources that the monks left behind, Kreiner reconstructs the techniques they devised in their lifelong quest to master their mindsfrom regimented work schedules and elaborative metacognitive exercises to physical regimens for hygiene, sleep, sex, and diet. She captures the fleeting moments of pure attentiveness that some monks managed to grasp, and the many times when monks struggled and failed and went back to the drawing board. Blending history and psychology, The Wandering Mind is a witty, illuminating account of human fallibility and ingenuity that bridges a distant era and our own.

Jamie Kreiner: author's other books

Who wrote The Wandering Mind: What Medieval Monks Tell Us About Distraction? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

What Medieval Monks

What Medieval Monks