First printed in hardback October 2011. First published in eBook format December 2011 by Veloce Publishing Limited, Veloce House, Parkway Farm Business Park, Middle Farm Way, Poundbury, Dorchester, Dorset, DT1 3AR, England. Fax 01305 250479/e-mail info@veloce.co.uk/web www.veloce.co.uk or www.velocebooks.com.

eBook edition ISBN: 978-1-845844-68-4

Paperback edition ISBN: 978-1-845842-88-8

David Alderton and Veloce Publishing 2011. All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review, no part of this publication may be recorded, reproduced or transmitted by any means, including photocopying, without the written permission of Veloce Publishing Ltd. Throughout this book logos, model names and designations, etc, have been used for the purposes of identification, illustration and decoration. Such names are the property of the trademark holder as this is not an official publication.

Readers with ideas for automotive books, or books on other transport or related hobby subjects, are invited to write to the editorial director of Veloce Publishing at the above address.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typesetting, design and page make-up all by Veloce Publishing Ltd on Apple Mac.

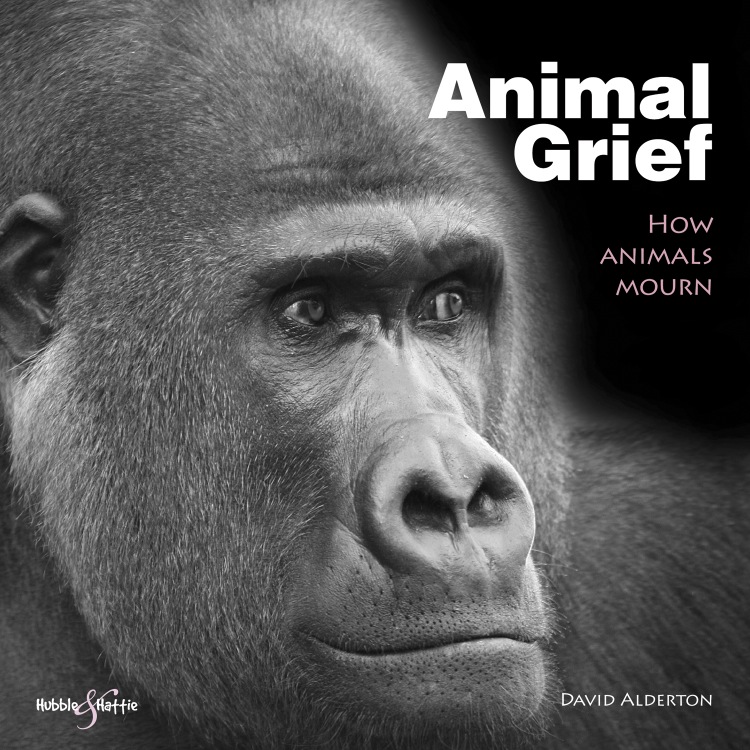

Changing times, changing ways

E motions in animals remain a controversial subject. Some people do not believe that animals are capable of feeling emotion generally, let alone grief, possibly because grief represents one of the most complex of emotions. It is acquired with age, rather than being innate like anger, and is not often displayed.

Many owners would privately accept that their pets do show signs of emotion, including grief, but these have been essentially anecdotal accounts, which have not been followed up. Today, though, thanks in part to the internet, there is much greater debate surrounding this topic, which has now triggered serious scientific interest.

Differing thoughts about the way in which animals perceive the world extend back to the dawn of history. These have been markedly influenced by the way in which animals have been perceived in different cultures. Unfortunately, our beliefs about emotions in animals have been clouded over the course of many centuries by theological dogma, and issues surrounding the human condition and soul. This has had the effect of blocking genuine investigation into this field.

A radical rethink of the concept of animal emotions is currently taking place today, however, inspired by the way in which science is providing some remarkable insights into animal behaviour. These findings are causing us to view the natural world in a completely different way.

Crocodilians, for example, have emerged as devoted parents, rather than mechanistic killers. Elephants can keep in touch with each other across long distances by using infrasound, which is inaudible to our ears. The song of whales reverberates through the oceans for the same purpose, albeit increasingly drowned out by interference from ships sonar.

The concept of the soul

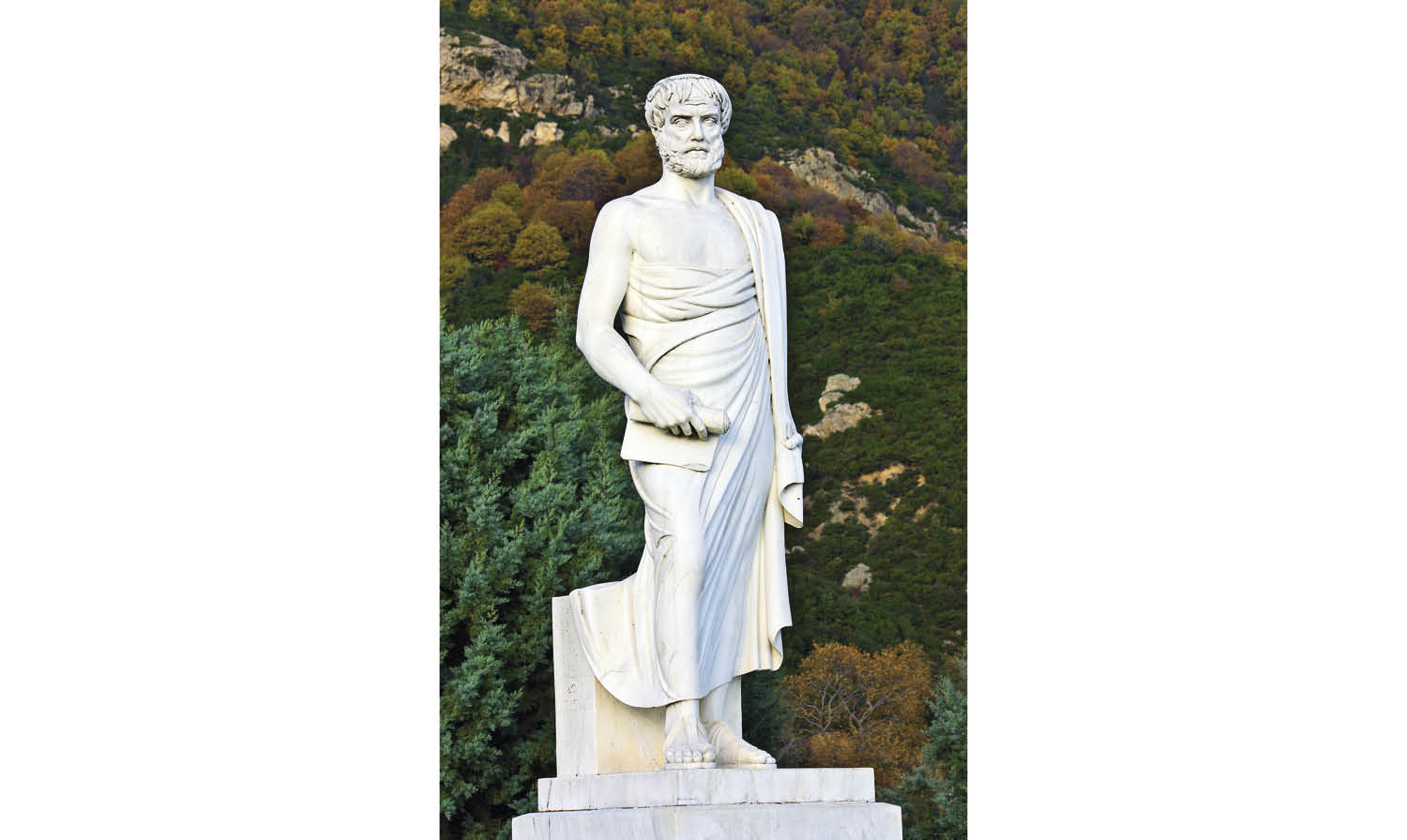

When it comes to discussions about whether or not animals can feel grief, these have been closely bound up over centuries with the concept of animal consciousness. The Greek philosopher Aristole (384-322 BC) was one of the first people to consider the possibility of animals having souls. What made his approach different, however, as set out in his work De Anima (meaning On the Soul ), was that he sought to consider this from a scientific rather than a theological perspective, unlike many later writers.

His conclusion was different, too, because he viewed the soul as the life force, rather than an entity that survived death, as encapsulated in subsequent Christian teaching, and that of other religions, too. Aristotle therefore considered that all life forms had souls, although he sought to distinguish between them.

Grief is an emotion that is linked with social awareness.

Plants, in his view, had the least sophisticated form of soul, as evidenced by the fact that they did not move. The soul of plants allowed them simply to grow and reproduce. Animals, in contrast, possessed a higher form of soul, combining a vegetative soul with a rational soul, which allowed them to feel things and move. Those of humans were at the highest level of all, though, because people are capable of being rational and possess the ability to reason.

A young crocodile rests on his mothers back.

Yet even Aristotle considered that one of the reasons why animals had a lesser soul was because, unlike people, they were incapable of having feelings. In Aristotles world, animals would not have been considered capable of feeling grief; this would have been the exclusive preserve of humans.

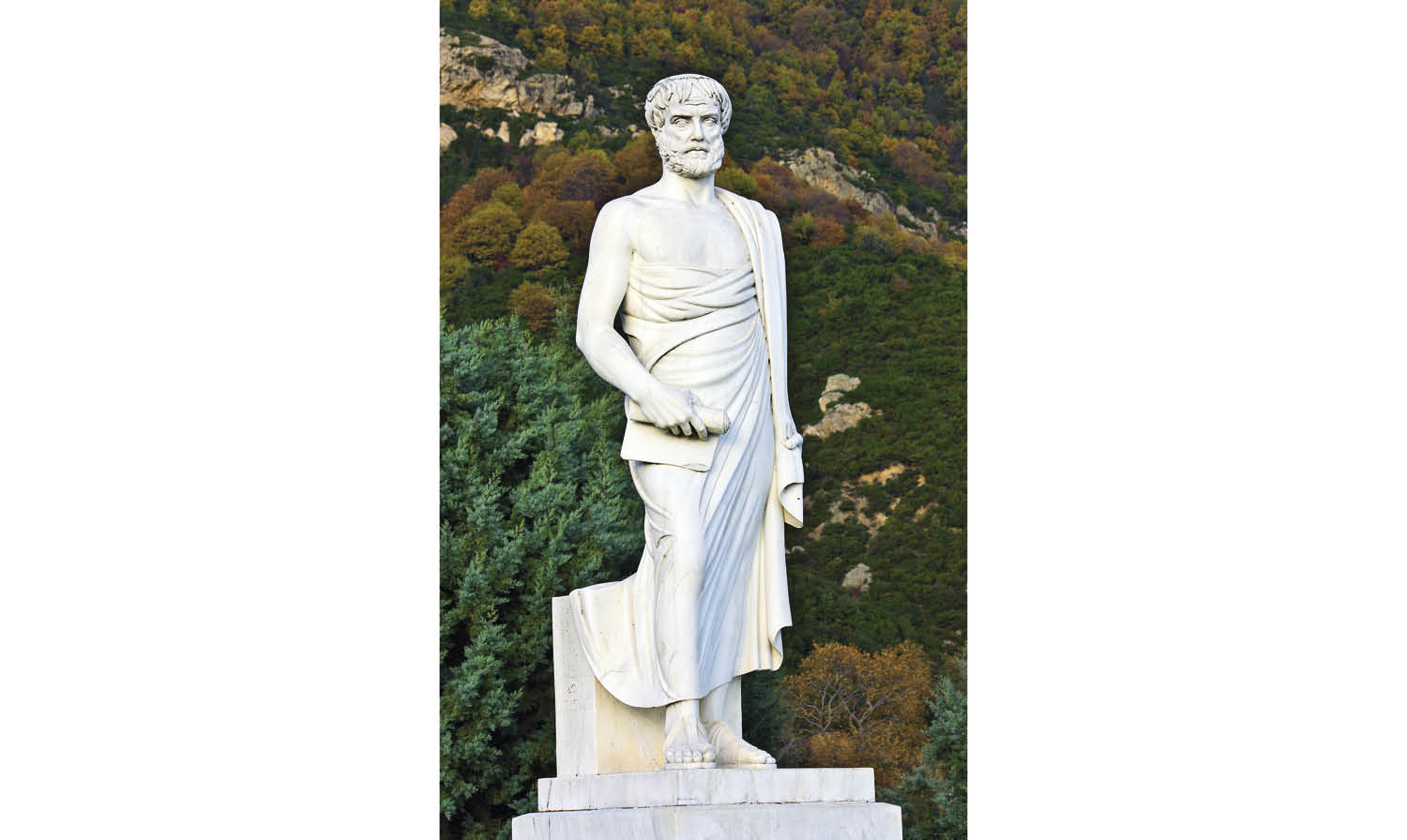

A statue of Aristotle at his birthplace at Stageira, Greece. Not only did he develop a concept of the soul, he also laid the foundations for modern-day zoology.

His approach was, nevertheless, quite radical, when set against established classical teachings up to that point. Plato had previously suggested that the soul was an independent entity which existed within the body, and survived death. Aristotle, however, was convinced that the soul represented life in the organism it inhabited, and could not survive death. He believed it was the soul which served to distinguish living creatures from inanimate objects.

Another point of distinction which is still apparent in our culture today is Aristotles assertion that the location of the rational soul lay not in the human brain, but rather in the heart.

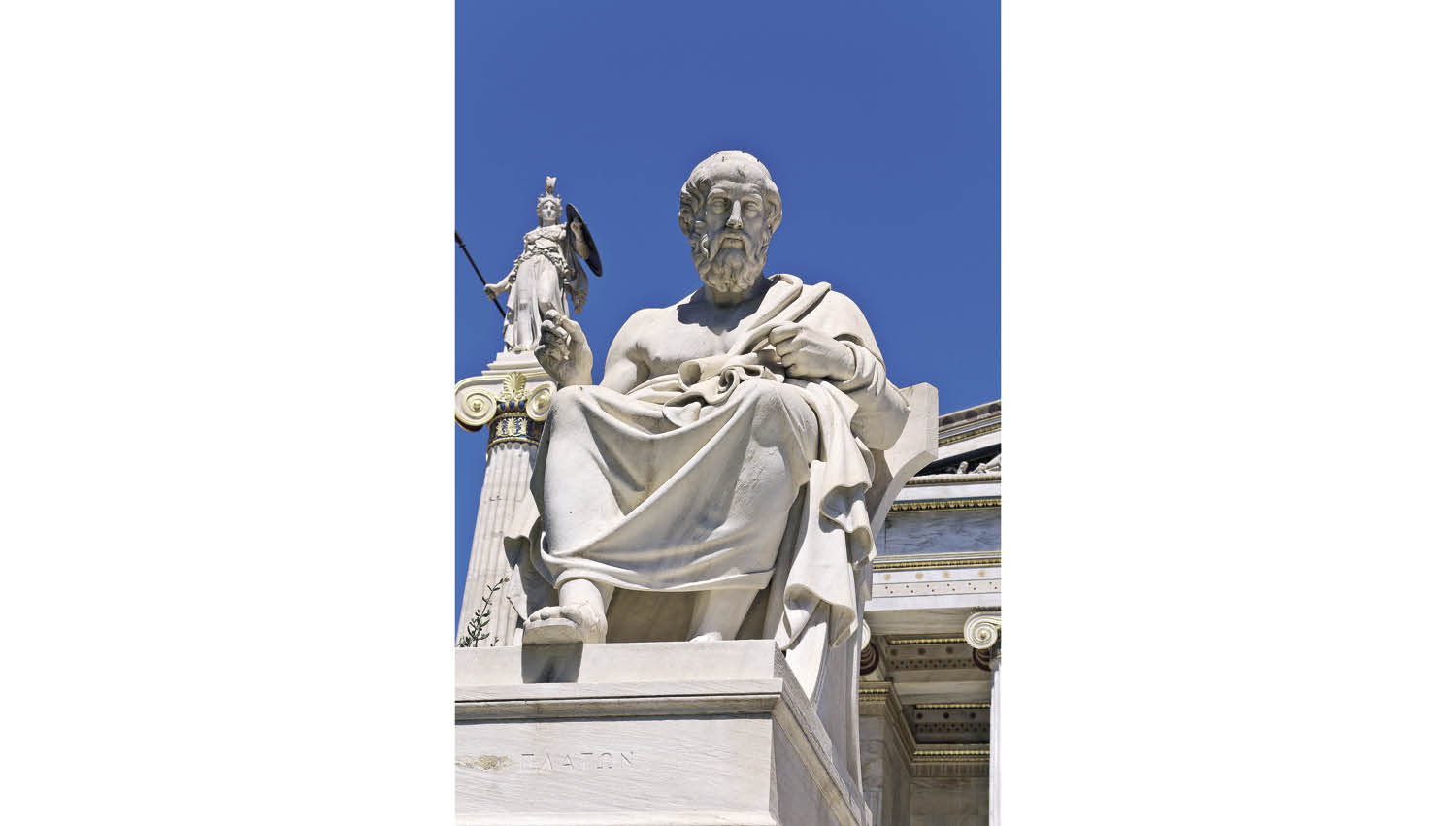

A statue honouring the ancient Greek philosopher Plato, which can be seen at the Academy of Athens building in Athens.

Aristotle developed the original scientific classification of animals, being the first to distinguish between what we now recognise as vertebrates and invertebrates. Alongside this, however, he also sought to create what he called a scala naturae , or great chain of being, which ranked life forms into eleven different groups, from plants at the bottom of the chain up to man, followed by God at the top. It was to have a major influence on our view of the natural order right through to the mediaeval period, and well beyond, with its influence still being apparent up until the 1800s.

There is no doubt that Aristotles work helped to lay the foundations for development of modern zoology, which is the branch of science covering the study of animals. He distinguished marine mammals from fish, for example, and also recognised that cartilaginous fish, such as rays and sharks, formed a separate group in their own right.