The No-State Solution

Copyright 2023 by Daniel Boyarin.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please email (U.K. office).

Set in Gotham and Adobe Garamond type by IDS Infotech, Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022938384

ISBN 978-0-300-25128-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

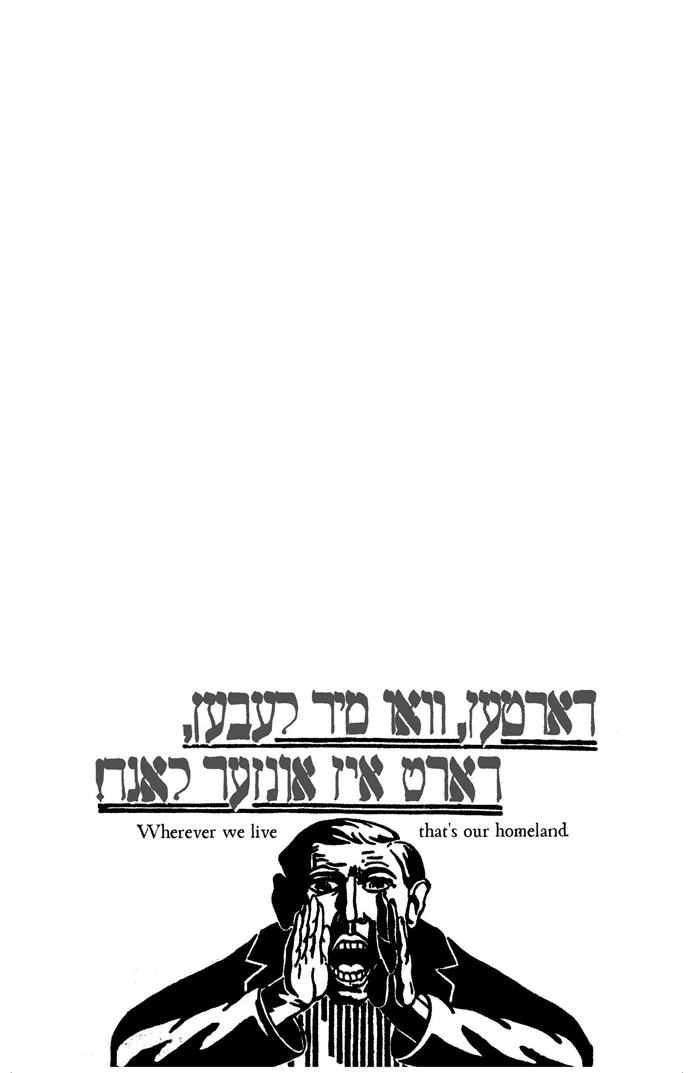

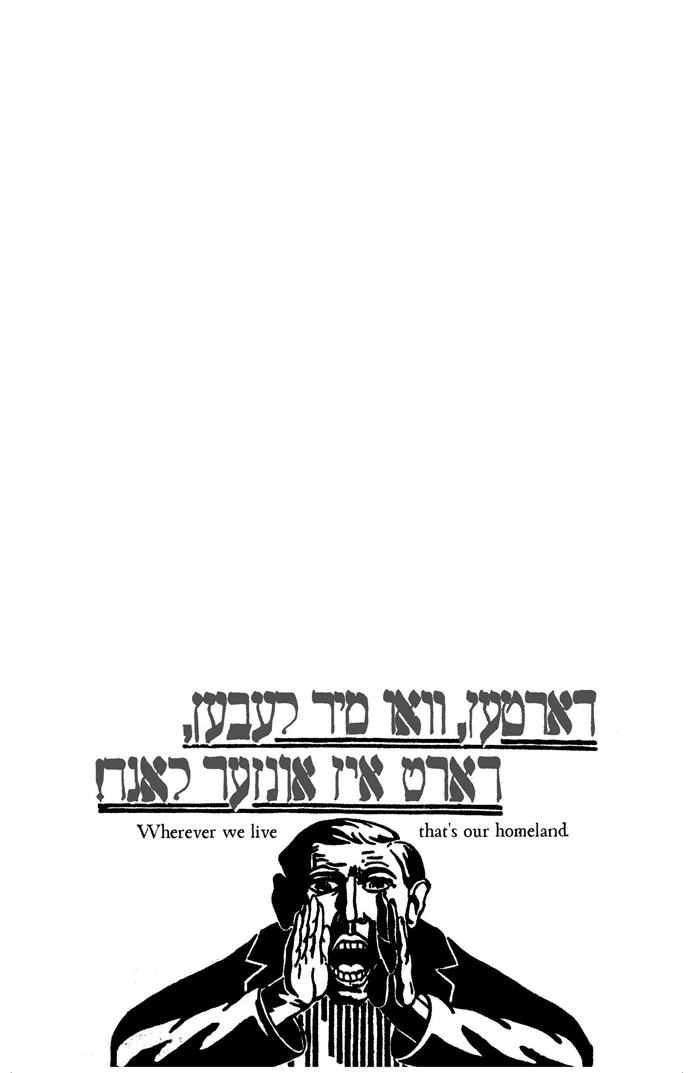

Frontispiece art by Aharon Nisn Varady, adapted from a General Jewish Labour Bund poster (Kiev, Ukraine, 1918), with an English translation of the original Yiddish heading. For the poster, see wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundposter1918.jpg.

Contents

Preface

After literally decades of obsessive thought about the Jewish Question, I seem to have gotten myself into an aporia, a dead end of thinking with no way out. One way of describing this impasse would be that two of my most ardent political commitmentsto full justice for Palestinians and to a vibrant, creative Jewish national cultureseem directly to contradict each other. It would seem as if the only way to fulfill the latter dream is to support the existence of the State of Israel, but clearly, the existence of the State of Israel makes the first dream impossible to fulfill. The forms, moreover, that this Jewish national culture takes in the Jewish state have always been problematicalinevitably so, I would argue, given the premises of such a state, even when pursued with the best will. This best will, furthermore, turns more and more sour almost by the day; it seems almost inevitably so. The nation-state is well on the way to being a racist, fascist state. Given the choice between justice and my culture, my nation, I have no choice but to choose justice, but the loss would be unsupportable. There is too much that I love, value, treasure, and enjoy deeply to become indifferent to the fate of the Jewish People and its works and days, and I have devoted too much of my lifes work (not my career, but my lifes work) to Yiddishkayt (Jewishness) to lose that struggle now. This loss would be for me not only unsupportable but virtually unthinkable. I am a Jew devoted to that predication and what it entails.

To frame this manifesto, I will begin with one of my first experiences of the dilemma. As a young teenager, I became deeply engaged with a Zionist socialist youth movement. What engaged me most (aside from the sheer excitement of militant involvement with comrades) were two aspects of the experience of the world it provided: a deep and thrilling absorption in Jewish history and culture, together with passionate desire that they continue, and an equal enthrallment with the idea of social justice for everyone: economic justice, cultural freedom, and equality for all the people and peoples of the world. The question of their relation was posed for me when the counselors informed us that the problem had been that too many Jews had been dedicated to universal social justice and not to the future of the Jews.

I bridledto say the least. For me, a Jewish connection to progressive causes was a precious legacy of the Jewish folk itself. The implicit and explicit message of these Zionists was that the only way possible to advance these two ideals together, a rich and vibrant continuation of Jewish culture, and a universalist commitment to all the peoples of the worldexcept, it seems, to the Palestinianswas the State of Israel, where the Jews would control their own fate. So we were taught. I remained unconvinced. Nevertheless, they did convince me of the need for an equal and socially just world, and they instilled in me a passion for continued Jewish existence and, even more, for continued Jewish vitality in all spheres of creative life.

But during the two decades during which I dwelled, studied, taught, served in the Army Reserves, and with my wife raised a family in Israel, I gradually came to the realization that these two ideals were actually in deep tension with each other, even incompatible in the conditions of a Wilsonian single-culture-dominated state with citizens of other culture groups defined as resident aliens (at best) and systematically, if not generally violentlythentreated as second-class citizens, or worse. The occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, the Golan, and Sinai only pointed up this impossible tension and contradiction even more. When I heard Yitzhaq Rabin say that the breaking of the arms and legs of children throwing stones was necessary to preserve the state, I repented of my erstwhile Zionism completely. Having evolved, then, during my years as an active citizen of the State of Israel into an active anti-Zionist, with, however, my commitment to Jewish identity and identification, Torah study, scholarship, practice, literature and liturgy, and modes of speech and thinking undiminished, even growing stronger and stronger, I have lived now for more than thirty years in the United States, experiencing the predicament ever more sharply: how can we remain a nationfor that is what I believe we are and should continue to beand retain at the same time our absolute dedication to social justice for all?

As I will explore at some length in the manifesto that follows, at issue here is nothing less than what it means to be a Jew, and for some time now, that question has been answered in two ways: to be a Jew is to be either a member of a religion or of a nationality grounded in the existence of a nation-state. I reject both these answers.

What do the terms religion and nation mean? As I will be at some pains to demonstrate below, religion is notoriously difficult to define, but in its modern usage it almost always devolves to the essentially Protestanteven essentially Lutherannotion of a belief system, disembedded from other forms of belonging, identity, and practice within a given nation. Such a view is embodied in English usage when we refer to the Jewish faith, as if belief in certain propositions were what made one a Jew. One consequence of this distinction is that one may be removed from a religion by the powers that be for believing badly or not at all, or for heretical practices, while one belongs to a nation whatever ones beliefs. As such, if the Jews are a religion, we can have Jews who belong to many nations. Nations have members; states have citizens. On that view, which I dont share, of course, one could be a Jew and also a member of some other nation: be a Jew at home and an Englishman abroad.

For some time, I have tried to show how the term religion, implying a faith and a sphere of life separated from kinship, politics, and economics, is inappropriate historically, particularly for the Jews, as well as for most folks in the world. Judaism as the name of a faith or religion is a new invention, a new usage, especially among Jews ourselves. The Jews, then, is not the name of a religion, and the Jews, historically, at any rate, are not a religion.

The alternative, nation, is somewhat less problematic from a historical point of view, for while there is no native Jewish term for religion

Next page