Science & Islam

A HISTORY

EHSAN MASOOD

ICON BOOKS

Published in the UK in 2009 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

3941 North Road, London N7 9DP

email:

www.iconbooks.co.uk

Previously published in the UK in 2009 by Icon Books

This electronic edition published in 2009 by Icon Books

ISBN: 978-1-84831-160-2 (ePub format)

ISBN: 978-1-84831-161-9 (Adobe ebook format)

Printed edition (ISBN: 978-1-84831-081-0)

Sold in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, 3 Queen Square,

London WC1N 3AU

or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

This edition published in Australia in 2009

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in Canada by

Penguin Books Canada,

90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario M4P 2YE

Text copyright 2009 Ehsan Masood

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any

means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset by Marie Doherty

Contents

Ehsan Masood is a science writer based in London. He writes for Nature and Prospect magazines and teaches international science policy at Imperial College London. He is a regular panellist on Home Planet on BBC Radio 4 and also presented Islam and Science, a three-part series for Radio 4 on science in todays Islamic world that was broadcast in 2009.

For my parents, Shamsa and Hassan Masood

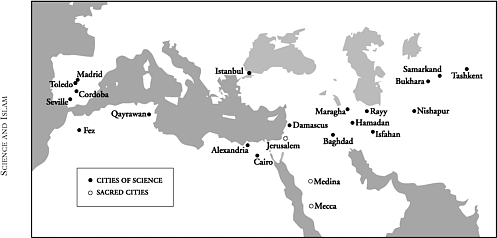

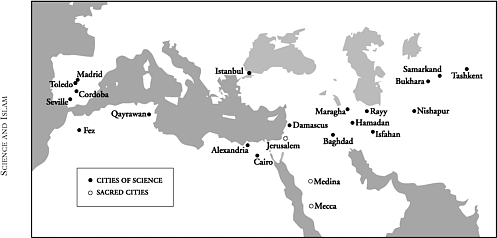

Urban knowledge: Islams cities of science from the 8th to the 16th centuries housed hospitals, observatories, libraries, colleges and schools for translation, as well as much individual research.

A note on language

A book on science during the Islamic empires presents some interesting challenges for the science writer of today writing in English, and at a time when a good deal of sensitivity surrounds the use of words and phrases on all things Islamic, or Muslim.

Questions to do with God and religion are not mainstream to the process of how science is done, nor its many and varied products. Because of this, science writing (at least in English) has yet to develop a comprehensive vocabulary on the topic of science and religion.

The publishers of Science and Islam: a History, however, couldnt wait for a dictionary on science and belief. They needed a consistent short-hand phrase to describe the science that took place during the empires that followed the birth of Islam. And several candidates were shortlisted for the job.

One option was to use Muslim science, except that not all of the scientists mentioned in the following pages were Muslims. Another option was to go for Arab science, except that many practitioners were not from the Arab world, even if they were Arabic-speaking.

As so often happens with dilemmas in cultural relations, the best solution was to look for a compromise. The phrase that this book employs to describe science in Islamic times is Islamic science. It isnt perfect by any means, but it comes closest to the mark.

An explanation of why Islamic science was chosen is needed, because to many readers Islamic science will be as nonsensical as Jewish science, Christian science, or Hindu science. Science is a universal tool for knowing about the world we live in: the individual beliefs of scientists have no bearing on the nature of what it is that they are investigating. One of the best examples of this is the 1979 Nobel prize in physics: this was shared between Muhammad Abdus Salam, a devout believer, and Steven Weinberg, a devout atheist.

To other readers, however, if something is Islamic this means it is related to the practice of faith. To this group of readers, therefore, Islamic science might mean a science that is influenced by Islamic values, much as, say, Islamic banking is used to describe financial systems that are governed according to Islamic guidelines; or in the same way that an Islamic school is an institution that educates children according to Islamic values.

Just to be clear, Islamic science in the context of this book also includes a science that has been shaped by the needs of religion.

The second challenge relates to the word science itself and what it means in languages such as Arabic, Persian and Urdu. The word science in its modern context means the systematic study of the natural world, using observation, experimentation, measurement and verification. It comes from the Latin word (from around the 14th century) scientia, which means to know.

Arabic manuscripts from Islamic times did not have a word for science as we know it today. Instead, they had a word similar in meaning to scientia, which is ilm (plural, uloom). Ilm means knowledge: this could be knowledge of the natural world, as well as knowledge of religion and other things.

Scientists in the Ottoman empire came closest to realising that ilm is not the same as the scientific method. They introduced a new word, fen (plural, funoon), which means tools or techniques. For example, a university of science would be written in Turkish Arabic as darul funoon, or a home for the techniques of science.

The new Ottoman convention, however, did not catch on. Turkish Arabic is all but extinct and Modern Arabic has retained the original dual usage for the word ilm. So, while the Arabic edition of Scientific American magazine is called Majalla Uloom (magazine of knowledge), at the same time, darul uloom (a home for knowledge) is used to describe religious seminaries all over the world.

Those who continue to use ilm to mean both scientific and religious knowledge argue that it represents an idea (common to Islamic cultures) that science and faith are two sides of the same coin: that they are equally valid forms of knowledge, and with similar if not equal claims to seek the most truthful answers to questions.

Others would disagree. Ilm may well be an accurate description for religious knowledge; however, there is a case to be made for finding a word that can distinguish between scientific and religious knowledge.

In languages such as Arabic and Urdu, acquiring ilm is a phrase that is commonly used in textbooks, in print and in the broadcast media. Knowledge of religion can of course be acquired or memorised, as can much scientific knowledge. But science has an important added dimension: it is also about experimenting, innovating, building, refuting and pushing at the boundaries of what we know.

Prologue

Picture, if you will, images from the 1969 moon landings: those grainy black-and-white photos or slow-motion TV shots of rockets and astronauts in space, and awe-inspired spectators watching from below. Or recall the television footage from 2000 when the human genome had been sequenced, with the news announced jointly by US President Bill Clinton and Britains Prime Minister Tony Blair.

What do these and so many more pictures of modern scientific discovery tell us? One message is very clear: that science is more than just science. It is the result of the vision of those who govern us about where they want to take their societies in the future. The moon landings told anyone watching that here was an empire at the top of its game. Having established its domain on earth, the most technologically-advanced society of its age was ready to claim the heavens or at the very least, a small part of it.