Contents

Introduction

It is said that water is the ideal drink for the human being, and that drinking water is good for ones health. The reasons why this would be the case, however, are rarely stated. As a consequence, water, as a drink, is often neglected as a factor in health.

This is especially unfortunate considering that water is so widely available and so low in cost.

Water plays a fundamental role in health. Drunk on a daily basis in sufficient quantity, it not only maintains the body in good working order but can also prevent and heal many disorders and health problems.

Who would imagine that fatigue, energy depletion, depression, eczema, rheumatism, high and low blood pressure, high cholesterol, gastric disorders, and premature aging could all be caused by a chronic lack of water in the body? Science has discovered that these problemsand a great many otherscan be effectively prevented or treated by correct hydration.

Most people assume they are drinking enough fluids. Certainly they consume copious amounts of coffee, tea, and all sorts of soft drinks, but these beverages are far less effective in hydrating the body than plain water. Furthermore, in todays world, our bodies need for water is much higher than it once was. Our food is too rich, too concentrated, and too salty, and the use of dehydrating substances such as alcohol and tobacco is very widespread. Stress, overheated and artificially ventilated homes, offices, and stores, air and water pollutionall contribute to our increased need for water.

As a consequence, large numbers of people do not realize that they are chronically dehydrated, much less that lack of water is the cause of many of their health problems. There is only one solution: drink a lot more water. But for people to make a permanent change in their habits, they need to know why water is so important. What exactly happens when water enters the body? What are the health conditions that can be traced to dehydration? How should we drink, and what water should we choose? These are just a few of the many questions answered in this book.

The final chapter presents ten simple remedies that show how drinking water as a therapeutic agent can have powerful curative effects.

Water and the Human Body

Our image of how the body is constructed and our understanding of how it functions determine how we use the body and treat it in the event of illness.

Unfortunately, an old mechanistic vision of the body that has been disproved by current physiological research still survivesmost often unconsciouslyin the way we consider the body. This outdated concept can lead us to overlook a fundamental factor: the important role in health played by water.

The old concept, known as solidism, views the body as a machine made up of solid cogs (the organs) in which fluids circulate (blood, lymph). The body is constructed of a combination of dry and hard materials, with fluids or water constituting a negligible or very minor component whose role is limited to oiling the machinery and transporting different substances from one part of the body to another.

This way of looking at things so permeates our reasoning process that when an illness makes its presence known, we focus our attention on the solid parts of the body: the organs. We give very little attention to the organic fluids from either a qualitative or, more important, a quantitative point of view.

Is there any justification for this lack of interest in the bodys fluids? No, quite the contrary. In fact, what is the human body primarily constructed from, if not water?

THE BODYS WATER CONTENT

Although the body is constructed of both liquid and solid materials, fluids are present in much greater quantity than solids. Physiology teaches us that water is actually the most important constituent of the body, accounting for 70 percent of the human bodys composition.

A human body weighing around 150 pounds therefore consists of some 105 pounds of fluids (in the form of blood, lymph, and cellular fluids), representing a little over two thirds of the bodys entire weight. The solid part of the body consists of only about 45 pounds. This is a far cry from a body built from solid materials with a little liquid thown in.

Furthermore, these figures are for the water content of an adult body. It is still higher during infancy, especially during the period of gestation. The body of a newborn is 80 percent water; that of a seven-month fetus, 85 percent; and that of a four-month fetus, 93 percent.

TABLE 1.1

THE BODYS WATER CONTENT BASED ON AGE |

|

| Age | Water Content (%) |

|

| 4-month fetus | 93 |

| 7-month fetus | 85 |

| newborn | 80 |

| child | 75 |

| adult | 70 |

| elderly person | 60 |

|

The fluids of the body are not all mixed together as if they were inside a large sack of skin. Rather, they are separated and allocated to different compartments throughout the body.

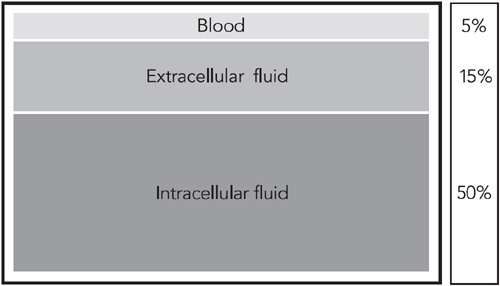

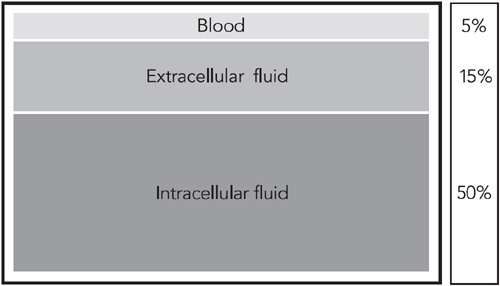

The fluid closest to the bodys surface is blood. It is the first to receive substances taken in by the body from the outside, such as oxygen brought in by the respiratory tract and nutritive material passed through the mucous membranes of the digestive tract. The blood represents 5 percent of the bodys weight, yet it circulates only within the arteries, veins, and capillaries of what is known as the vascular network.

Directly beneath the vascular network is another compartment containing extracellular fluid and lymph (figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. The three physical compartments or levels and their weight percentages in the body

As its name indicates, extracellular fluid is found outside the cells. It surrounds them like a bath, filling the small spaces or interstices that separate the cells from one another; it is also known as interstitial fluid. It forms the external environment of the cells, the great ocean in which they float. This fluid receives oxygen (in fluid form) and nutritive substances carried by the bloodstream, and then it transports them to the cells, where this cargo is utilized. The extracellular fluid also receives the waste products and residues produced by the cells and transports them up to the higher compartment, the bloodstream, which in turn takes them to the excretory organs (liver, kidneys, etc.) so they can be filtered and eliminated (figure 1.2).

Next page