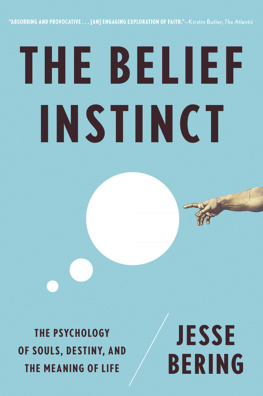

The BELIEF INSTINCT

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF SOULS, DESTINY, AND THE MEANING OF LIFE

Jesse Bering

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY New York London

Copyright 2011 by Jesse Bering

Originally published in Great Britain under the title The God Instinct: The Psychology of Souls, Destiny, and the Meaning of Life

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

ISBN: 978-0-393-08041-4

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Itd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

For my father, William

CONTENTS

THE CHILD : Im frightened.

THE WOMAN : And so you should be, darling. Terribly frightened. Thats how one grows up into a decent, god-fearing man.

Jean-Paul Sartre, The Flies (1937)

L ETS FACE ITBOOKS about science and religion can be awfully dull. And there isnt exactly a shortage in the marketplace in this particular genre. So for these reasons Im especially grateful to a patient group of people in the publishing world who listened to me long enough to realize that, perhaps, I might have something a little bit different to say on that tired old horse of a subject, the existence of God. Were it not for these peoples support, the book that youre holding in your hand right now would probably be busily growing cobwebs in a rare booksellers boutique, sandwiched among a dozen obscure, self-published books on metaphysics or reincarnation or some such impenetrable emanations of the authors strange, hallucinatory matter.

These supportive people include my agent, Peter Tallack of The Science Factory, who patiently held my hand from the very first day and helped me navigate a publishing universe that was quite foreign to me; and Angela von der Lippe and Nick Brealey, my editors at W. W. Norton and Nicholas Brealey Publishing, respectively, whose critical and talented eyes forced me to rethink, reedit, and rewrite this book a few times over. As such things go, Im reasonably certain that, in a few years time, should I survive that long, Ill look back with embarrassment on many things that Ive written in this volume. But hopefully this blushing regret will be owing to the personal anecdotes rather than to the central arguments, and Angela and Nick certainly cannot be held accountable for those unfortunate bits of my own ridiculous life. In addition, publishing assistants Laura Romain and Erica Stern, of W. W. Norton, were exceedingly helpful at both ends of the production process. Last but not least, I would like to thank my copy editor, Stephanie Hiebert, who performed miracles worthy of the Almighty in cleaning up this text.

My students, as well as many other people in my day-to-day life, graciously endured many fleeting bouts of crankiness and my occasional absence of both body and mind while I was working on this manuscript. I only hope they forgive me these things someday. My partner, Juan Quiles, is still miraculously with me, in spite of everything. Im also very grateful for the many friends, family members, and colleagues who generously gave their time to read early chapter versions (in some cases, the entire unedited manuscript) and whose clear comments and ideas helped give shape to the finished product. Among others, these include David Bjorklund, Paul Bloom, Joseph Bulbulia, Nicholas Epley, Margaret Evans, Gordon Gallup, Marc Hauser, Nicholas Humphrey, Dominic Johnson, Deborah Kelemen, E. Thomas Lawson, Graham Macdonald, Joel Mort, Shadd Muruna, Karen Schrock, Todd Shackelford, David Sloan-Wilson, Richard Sosis, Paulo Sousa, Henry Wellman, and Harvey Whitehouse. My former and present PhD students at the Institute of Cognition and Culture at Queens University Belfast, particularly Natalie Emmons, David Harnden-Warwick, Bethany Heywood, Gordon Ingram, Hillary Lenfesty, Jared Piazza, Lauren Swiney, Claire White, and Neil Young, have contributed substantially to my thinking, through their clever insights and innovative research ideas.

Finally, because the theoretical story simply took me where it led, no more and no less, I wish to give a special thanks to all those talented scholars whom I have inadvertently offended by failing to cite their work in this book. There are probably many and sundry otherwise gentle intellectuals and scientists who will want my head for this.

The BELIEF INSTINCT

G OD CAME FROM an egg. At least, thats how He came to me. Dont get me wrong, it was a very fancy egg. More specifically, it was an ersatz Faberg egg decorated with colorful scenes from the Orient.

Now about two dozen years before the episode Im about to describe, somewhere in continental Europe, this particular egg was shunted through the vent of an irritable hen, pierced with a needle and drained of its yolk, and held in the palm of a nimble artist who, for hours upon hours, painstakingly hand-painted it with elaborate images of a stereotypical Asian society. The artist, who specialized in such kitsch materials, then sold the egg along with similar wares to a local vendor, who placed it carefully in the front window of a side-street souvenir shop. Here it eventually caught the eye of a young German girl, who coveted it, purchased it, and after some time admiring it in her apartment against the backdrop of the Black Forest, wrapped it in layers of tissue paper, placed it in her purse, said a prayer for its safe transport, and took it on a transatlantic journey to a middle-class American neighborhood where she was to live with her new military husband. There, in the family room of her modest new home, on a bookshelf crammed with romance novels and knickknacks from her earlier life, she found a cozy little nook for the egg and propped it up on a miniature display stand. A year or so later she bore a son, Peter, who later befriended the boy across the street, who suffered me as a tagalong little brother, the boy who, one aimless summer afternoon, would enter the German womans family room, see the egg, become transfixed by this curiosity, and crush it accidentally in his seven-year-old hand.

The incident unobserved, I hastily put the fractured artifact back in its place, turned it at an angle so that its wound would be least noticeable, and, to this day, acted as though nothing had ever happened. Well, almost. A week later, I overheard Peter telling my brother that the crime had been discovered. His mother had a few theories about how her beloved egg had been irreparably damaged, he saidone being a very accurate and embarrassing deduction involving, of all people, me. When confronted with this scenariothrough first insinuation and then full-blown accusationsand wary of the stern German matriarchs wrath, I denied my guilt summarily. Then, to get them off my back, I did the unthinkable. I swore to God that I hadnt done it.

Lets put this in perspective. Somewhere on a quiet cul-de-sac, a second-grader secretly cracks a flashy egg owned by a woman whos a little too infatuated with it to begin with, tells nobody for fear of being punished, and finally invokes God as a false witness to his egged innocence. Its not exactly the crime of the century. But from my point of view, at that moment in time, the act was commensurate with the very worst of offenses against another human being. That I would dare to bring God into it only to protect myself was so unconscionable that the matter was never spoken of again. Meanwhile, for weeks afterward, I had trouble sleeping and I lost my appetite; when I got a nasty splinter a few days later, I thought it was Gods wrath. I nearly offered up an unbidden confession to my parents. I was like a loathsome dog whimpering at Gods feet. Do with me as you will, I thought to myself; Ive done wrong.