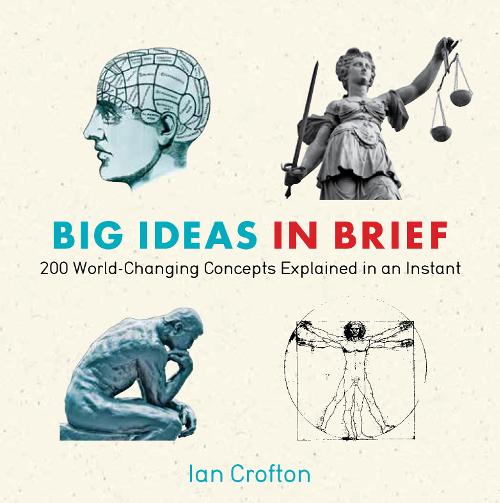

Big Ideas in Brief

Big Ideas in Brief

Ian Crofton

New York London

2013 by Ian Crofton

First published in the United States by Quercus in 2013

Design and editorial by Pikaia imaging

Illustration by Tim Brown and Patrick Nugent

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to Permissions c/o Quercus Publishing Inc., 31 West 57th Street, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10019, or to permissions@quercus.com.

e-ISBN: 978-1-62365-094-0

Distributed in the United States and Canada by Random House Publisher Services

c/o Random House, 1745 Broadway

New York, NY 10019

All pictures are believed to be in the public domain except:

: Roger-Viollet/TopFoto.

www.quercus.com

Contents

Introduction

W hat makes a big idea big? In 1953 the British philosopher Isaiah Berlin published a famous essay entitled The Hedgehog and the Fox, based on a fragment from a lost fable by the ancient Greek poet Archilochus: The fox knows many little things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.

Berlin used this little fable as the basis for dividing the worlds great thinkers and writers into two categories, the foxes and the hedgehogs. A hedgehog has one big idea and sees the world entirely through this single lens. Berlin cites a number of examples of hedgehogs, including the philosophers Plato, Hegel, and Nietzsche, and the writers Dante, Dostoevsky, Ibsen, and Proust. In contrast foxesincluding Aristotle, Shakespeare, Montaigne, and Goethedraw on a wide range of ideas and experiences and view the world from a variety of perspectives.

This book includes a number of big hedgehog ideasPlatos Forms, Hegels idealism, Marxs dialectical materialism, to name but a few. But its broad scope, its willingness to include many mutually contradictory concepts, its questioning of assumptions, all make it very much a tricky sort of enterprise.

Although drawing on a range of academic disciplines, this small book makes no claims to comprehensiveness. Rather, it selects a number of ideas that general readers may feel they ought to know a little about and gives them a succinct summary of the key points. By far the longest sections are devoted to philosophical and political ideas, for which no apology is made, but the reader will also find a range of topics drawn from religion, science, economics, sociology, anthropology, psychology, and the arts. For those wanting a fuller treatment of scientific ideas, there is an entire volume in the same series devoted to that subject.

Ian Crofton

May 2011

Philosophy

T he term philosophy comes from the ancient Greek word philosophos, meaning lover of wisdom, and for the ancient Greeks philosophy had a very wide scope. Today, we take a narrower view of what constitutes philosophy, an activity which has been defined as the critical examination of the basis for fundamental beliefs of what is true and the analysis of the concepts we use in expressing such beliefs.

The Greek philosophers before Socrates (c. 469399 BC) were predominantly concerned with speculations regarding the physical world, such as the nature of matter or the shape of the universe. Such inquiries became known in the Middle Ages as natural philosophywhat we now call science.

Science can be classified as a first-order activity, concerned with discovering the truth about the physical world. Another first-order activity is moralizingtelling us what actions are good and which are bad. Philosophy, in contrast, is a second-order activity, one that examines the assumptions lying behind first-order activities.

Socrateswhose thinking is only preserved through dialogues written down by his pupil Plato (see )turned the focus of philosophy onto questions involving humanity, such as What is good? This was the beginning of ethics, the branch of philosophy that seeks to clarify the basis of moral judgments. Socrates also developed methods of testing the validity of argumentsthe beginnings of logic.

Ethics and logic are two of the major branches of philosophy. A third major branch, metaphysics, asks questions about the ultimate nature of reality, such as What is being? Other fields within philosophy include epistemology, which studies the nature of knowledge; and aesthetics, which examines the nature of beauty and art and questions the basis of critical judgments. In addition, there are philosophies of a wide range of other first-order subjects, such as science, history, and political theory.

Reason

R eason is a word with a variety of shades of meaning. It is the human faculty that enables us to make logical inferences, arguing from the general to the particular (deduction) or from the particular to the general (induction). For some philosophers, reason denotes the intellect regarded as a source of knowledge, as opposed to experience.

Reason is often contrasted with emotion or imagination or insanity or faith. In the thirteenth century, St. Thomas Aquinas sought to reconcile faith and reason, giving the latter a place in Christian theology.

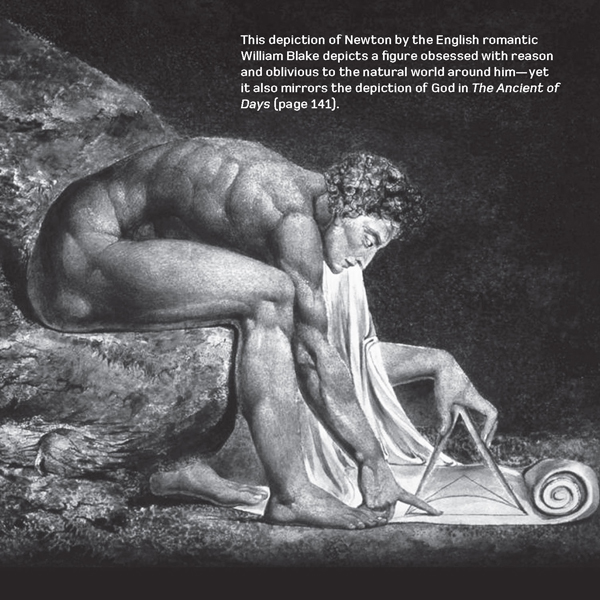

In the eighteenth century, thinkers of the Enlightenment emphasized the primacy of reason, seeking to abolish superstition and intolerance, and to reform the public sphere on rational lines. In reaction, the Romantic movement that arose toward the end of the eighteenth century emphasized the centrality of individual feeling in human experience (see ).

Platonism

T he whole of Western philosophy has been described as a series of footnotes to Platosuch has been the enduring influence of the ancient Greek philosopher. Plato (c. 427347 BC) lived and taught in Athens, where he set up a school of philosophy known as the Academy. He was a pupil of Socrates (see ), and most of his writings are written in the form of dialogues between Socrates and his followers. It is unknown how closely these represent Socratess own thought, as opposed to that of Plato himself.

The dialogues employ what is known as the Socratic method, in which Socrates pretends ignorance and asks a follower questions, leading them on until they contradict themselves. In this way, issues are clarified, and a closer approach is made to the truth. The early dialogues are concerned with virtues such as piety and courage, and appear to conclude that virtue is knowledge, and that wrongdoing is the result of ignorance. Of particular significance is the method itself, involving the rigorous challenging of assumptions and an insistence upon logical argumentthe hallmarks of true philosophy.

Next page