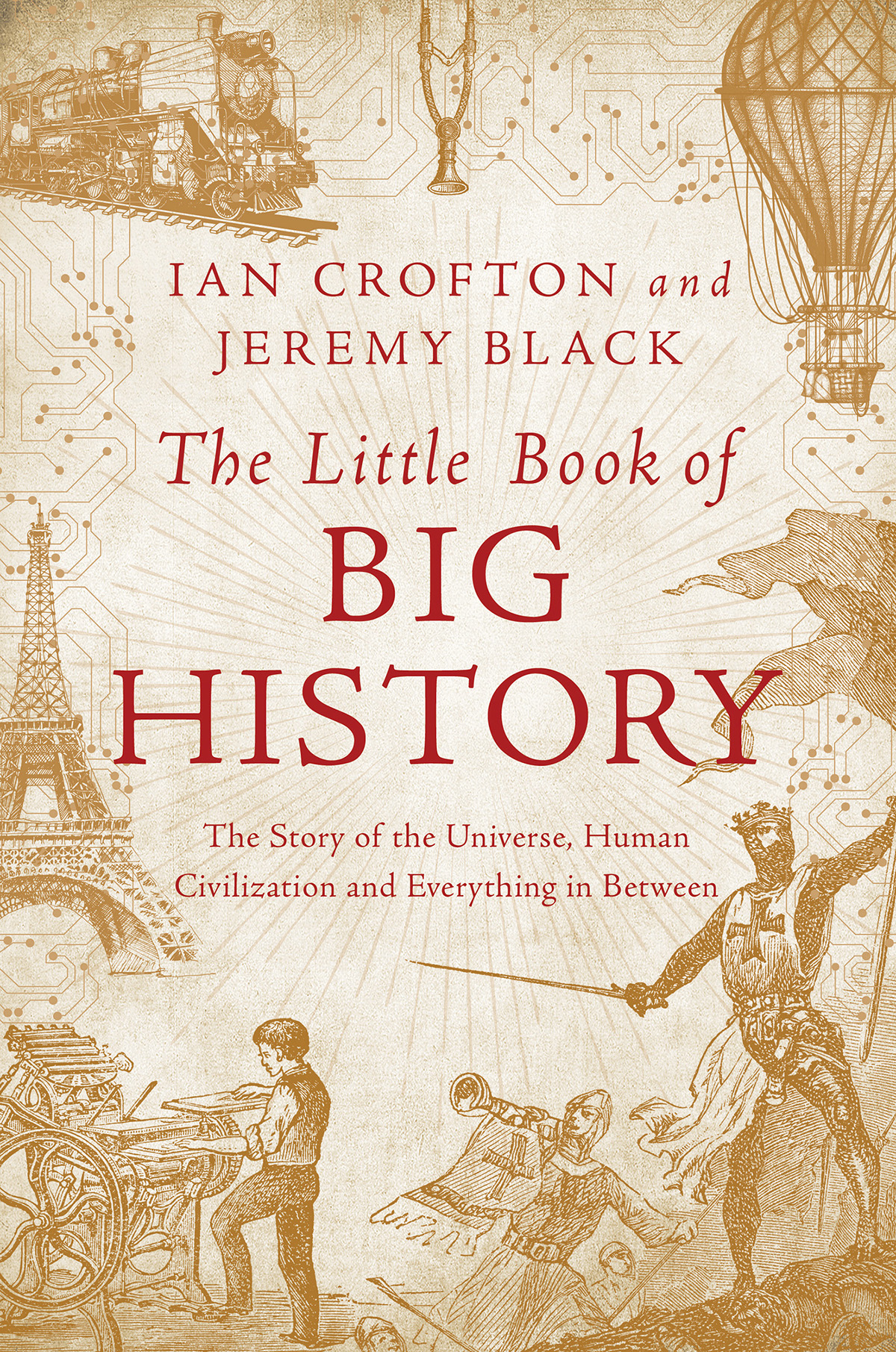

The Little Book of

BIG

HISTORY

The Story of the Universe, Human Civilization, and Everything in Between

IAN CROFTON and JEREMY BLACK

T HE L ITTLE B OOK OF B IG H ISTORY

Pegasus Books Ltd

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2016 by Ian Croften and Jeremy Black

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition July 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-436-7

ISBN: 978-1-68177-488-6 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Contents

Note: Rather than the Christian BC and AD chronology, more recent dates in Earths history appear here as BCE and CE , before and after the start of the Common Era.

How did we get to where we are now? The back story to the chronicle of humanity is a long one. There would be no human history without a physical place for it to unfold. So to truly understand ourselves, we have to understand how the universe came into being, how the stars and planets formed, why our planet has the right conditions for life to have appeared. And we also need to understand how living things work, and how they evolved, and how we have ended up with us.

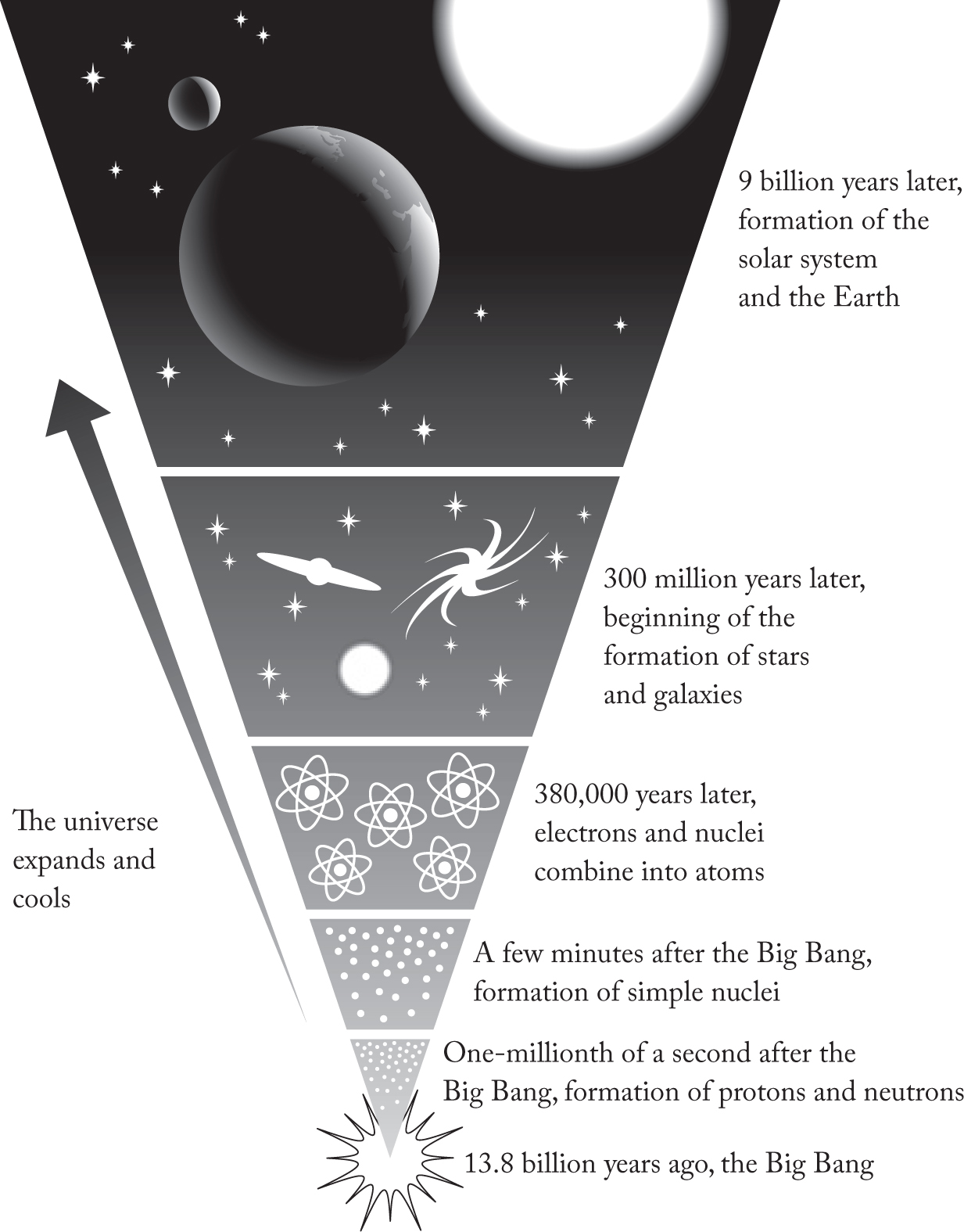

13.8 billion years ago: The Big Bang brings the universe into existence.

4.6 billion years ago: Formation of our solar system, including the Sun, the Earth and the other planets.

4.5 billion years ago: The Moon is formed, probably as a result of a collision between the Earth and a Mars-sized planet.

4.2 billion years ago: Oceans may have begun to form.

4.13.8 billion years ago: Earth and other inner planets suffer numerous impacts from asteroids.

4 billion years ago: Formation of oldest rocks still present on the Earth. Possible appearance in the oceans of self-replicating molecules, such as DNA.

3.7 billion years ago: Earliest indirect evidence of life on Earth suggests bacteria-like organisms feeding on organic molecules.

3.4 billion years ago: Cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) emerge, which draw energy from photosynthesis.

2.45 billion years ago: Start of the build-up of free oxygen in Earths atmosphere, as a by-product of photosynthesis.

Before the advent of modern science, there was a range of beliefs about the age of the Earth, and of the universe. Some Christians believed that God created both a mere 6,000 years ago. Ancient Hindu texts, in contrast, talk of an infinite cycle of creation and destruction.

Towards the end of the 18th century, geologists began to realize that the Earth must be much more ancient than had been thought (at least in Europe) perhaps millions if not billions of years old. However, into the 20th century the scientific consensus was that the universe itself was eternal, and in a steady state. Stars might be born and die, but the dimensions of the universe were fixed and unchanging.

A chink in this theory came in the 1920s when the American astronomer Edwin Hubble observed that the further away a galaxy is from us, the faster it is receding. He concluded that the universe is expanding, and that this expansion started in a single great explosion, which became known as the Big Bang.

Arguments persisted between the proponents of the steady state and those of the Big Bang. Then in 1964 two radio astronomers working in New Jersey, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, noticed that their sensitive microwave receiver was suffering from constant interference, the same in all directions, with a wavelength representing a temperature of 2.7 degrees above absolute zero. At first they thought the phenomenon might be caused by the proximity of New York City or by pigeons defecating on their instrument. Eventually they realized that what their receiver was picking up was an echo of the Big Bang. If you retune your radio, part of the white noise you hear between stations is this very same echo from the beginning of time.

The Big Bang

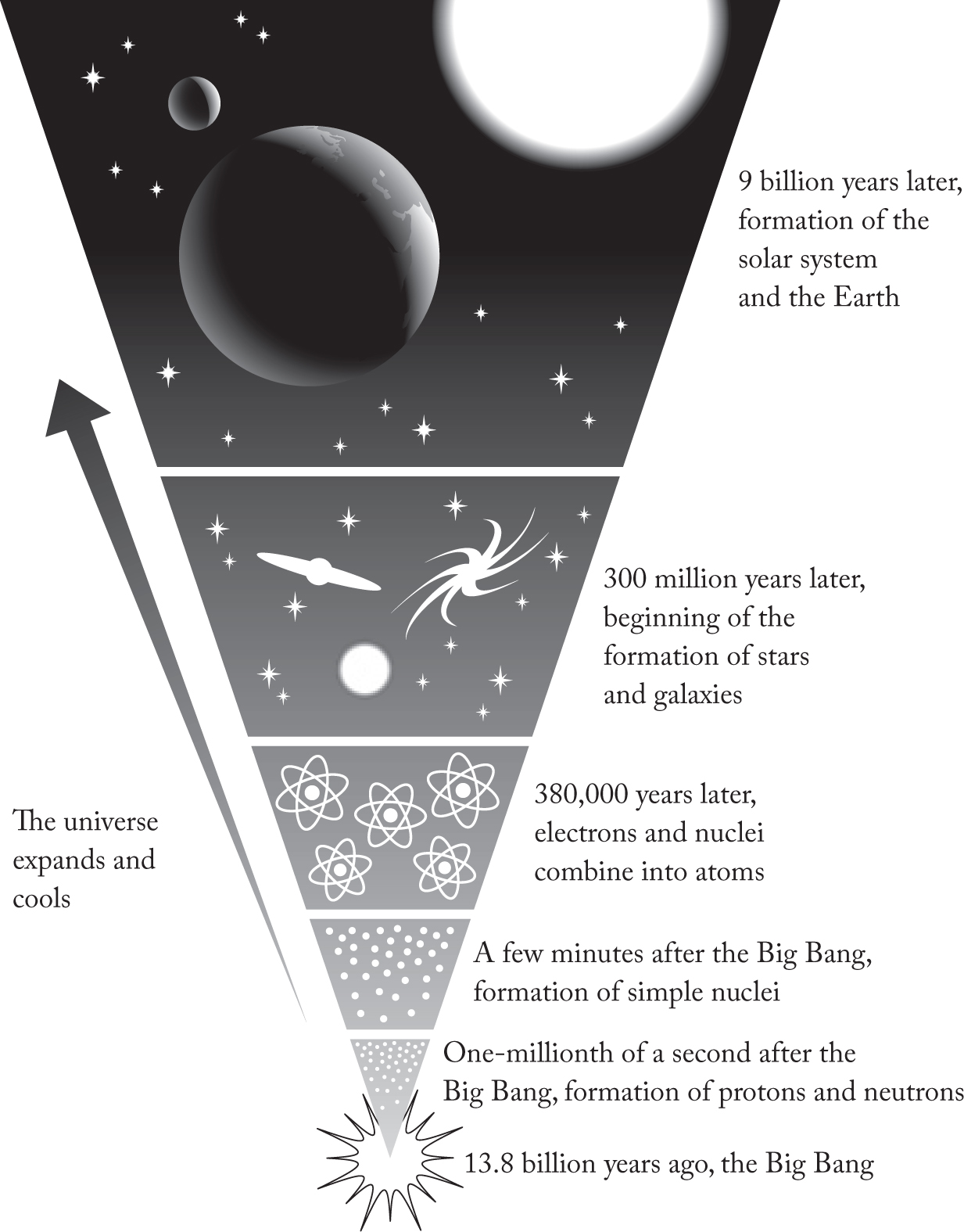

At this stage the only matter was elementary particles such as quarks and gluons. At about 106 seconds, as expansion slowed down and temperatures fell, quarks and gluons came together to form protons and neutrons. A few minutes later the temperature had cooled further, to about 1 billion degrees, and protons and neutrons combined to form the nuclei of deuterium and helium, though most protons remained unattached as hydrogen nuclei. Eventually, the positively charged nuclei attracted negatively charged electrons to create the first atoms. These simple atoms were to become the building blocks of the stars.

Why does the universe go to all the bother of existing?

Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time (1988)

As the early universe expanded, matter was evenly distributed through space. But as tiny irregularities in density began to appear, gravity began to play a role, with denser regions attracting more and more matter. In this way clouds of gas, largely comprising hydrogen and helium, were formed. These so-called nebulae were where stars were and continue to be born.

Within a nebula, denser areas may begin to collapse in on themselves because of gravity, and these areas may eventually become dense and hot enough for nuclear fusion to begin a reaction in which hydrogen is converted to helium, producing vast amounts of heat and light. It is this process that causes the stars including the Sun to shine with such intense brightness.

Just as gravity pulls together denser areas of gas to form stars, so it gathers stars to form galaxies. Our galaxy, the Milky Way, contains 100400 billion stars and has a diameter of around 100,000 light years meaning that light travelling at a speed of 300,000 kilometres per second takes 100,000 years to pass across it. Our Sun lies on one of the spiral arms of our galaxy, about 30,000 light years from the centre. The nearest star to the Sun is Proxima Centauri, just 4.24 light years away. The Milky Way is one of at least 100 billion galaxies in the universe. The size of the universe is a subject of speculation, but the part of it we can observe is 93 billion light years in diameter.

The wonder is, not that the field of the stars is so vast, but that man has measured it.

Anatole France, The Garden of Epicurus (1894)

Different sizes of stars may undergo particular sequences in their lifetimes. Those similar in size to the Sun burn at something like 6,000 degrees on the surface (the core is much hotter) for at least 10 billion years before they exhaust their hydrogen. At this stage, the core contracts and the temperature rises to 100 million degrees, allowing helium fusion to begin. The star expands to become a red giant, around 100 times larger than in its youth, before shrinking to become a white dwarf, 100 times smaller than the original.

Larger stars have shorter lives. For example, a star ten times the size of the Sun will turn into a red giant after only 20 million years. As the temperature increases, the star begins to synthesize heavier and heavier elements, until at 700 million degrees iron is created. This process is the origin of many of the elements that make up planets such as the Earth not only iron, but also carbon, oxygen and silicon. At this point the star blows apart in a massive explosion called a supernova, a fast-expanding cloud of gas and dust. At its centre is an object called a neutron star, only 10 to 20 kilometres in diameter, but so dense that a cubic centimetre of its material has a mass of 250 million tonnes. Even larger stars may end their lives as a black hole, an area of space so dense that not even light can escape its immense gravitational pull. There may be a supermassive black hole at the centre of our own galaxy.

Next page