GILBERT SELDES (18931970), the younger brother of famed foreign correspondent and investigative journalist George Seldes, was an influential American journalist, writer, and cultural critic, noted for championing the popular arts. Born into the Jewish agricultural community of Alliance Colony, New Jersey, to philosophical anarchist parents of Russian Jewish descent, he attended Philadelphias prestigious Central High School and graduated from Harvard University, where he became friends with e. e. cummings and John Dos Passos. After working as a newspaper reporter in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., and as a war correspondent in England during World War I, he joined the staff of The Dial and became the New York correspondent for T. S. Eliots The Criterion. In 1923, however, he went to Paris to write a book in praise of popular culture. The result, The Seven Lively Arts, appeared the following year to both considerable acclaim and criticism for its celebration of the likes of Al Jolson over John Barrymore and Charlie Chaplin over Cecil B. DeMille. In Paris, Seldes met and married Alice Wadhams Hall; the couple would have two children, Timothy, a literary agent, and Marian, a Tony Award-winning actor. Seldes later wrote columns for The Saturday Evening Post and Esquire, adapted Lysistrata and A Midsummer Nights Dream for Broadway, made historical documentary films, wrote radio scripts, and became the first director of television for CBS and the founding dean of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. His other many books of cultural criticism and social analysis include The Years of the Locust (1932), The Movies Come from America (1937), The Great Audience (1950), and The Public Arts (1956). Seldes also published a novel, The Wings of the Eagle (1929), and, under the name Foster Johns, two books of detective stories.

GREIL MARCUS is the author of The Shape of Things to Come: Prophecy and the American Voice, Lipstick Traces, and other books; with Werner Sollors he is the editor of A New Literary History of America. In recent years he has taught at the University of California at Berkeley, Princeton University, the New School University, and the University of Minnesota. He was born in San Francisco and lives in Oakland.

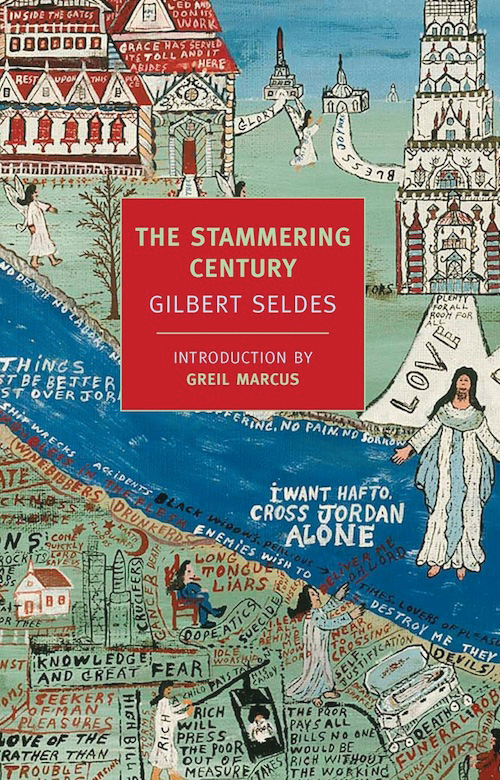

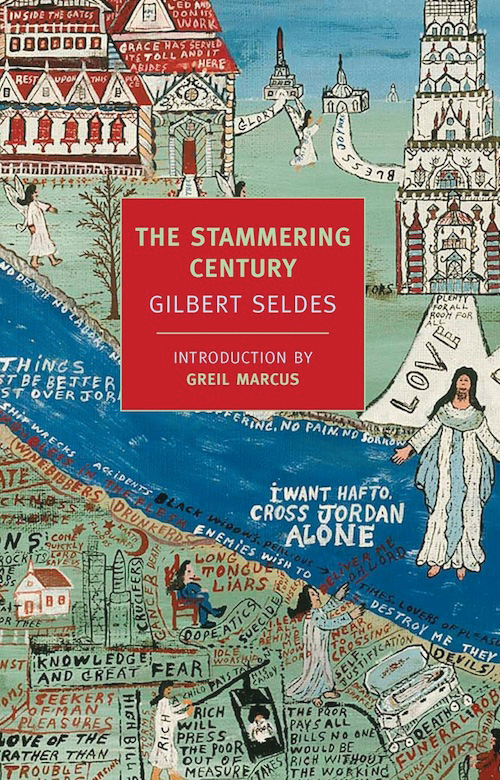

THE STAMMERING CENTURY

GILBERT SELDES

Introduction by

GREIL MARCUS

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 1927, 1928 by Gilbert Seldes

Introduction copyright 2012 by Greil Marcus

All rights reserved.

Cover image: Howard Finster, THE LORD WILL DELIVER HIS PEOPLE ACROSS JORDAN, AND MOON BECAME AS BLOOD,THER SHALL BE EARTH qUAKES (detail), Smithsonian American Art Museum. Photograph courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. / Art Resource, NY

Cover design: Katy Homans

The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier printing as follows:

Seldes, Gilbert, 18931970.

The stammering century / by Gilbert Seldes ; introduction by Greil Marcus.

p. cm. (New York Review Books classics)

Originally published: New York : The John Day Co., 1928.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59017-580-4 (alk. paper)

1. United StatesCivilization. 2. Social reformersUnited States. 3. United

StatesSocial conditions. 4. United StatesIntellectual life. I. Title.

E169.1.S46 2012

973dc23

2012016600

ebook ISBN: 978-1-59017-595-8

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

Introduction

I CAME gradually to want to prove nothing, Gilbert Seldes writes in his introduction to The Stammering Century. This simple sentence is a key to this galvanic, awestruck chronicle of the revivals, cults, utopian communities, and radical reform movements that under Seldess gaze come together as a shadow history of the United States in the nineteenth century. His original idea, he said, was a timid protest against the arrogance of reformers in generalto strip the persecuted reformers of their claims to sainthood or martyrdom by pious comparison: I am persecuted, Christ was crucified, therefore I am Christ. It occurred to me, Seldes wrote in perhaps the only really dull sentence of this book, that a study of self-constituted saviors might serve as a check to this form of spiritual snobbery. But Seldes found himself caught up in his story. He realized that to let his subjects speak in their own voices, to make their own kind of sense or nonsense, to give them the rope to hang themselves if that was where the story went, was a far greater thing.

The book was published in 1928; it was, Seldes wrote much later, an attempt to get to the nature, the essential character of Americaand the nineteenth century was when America discovered itself. It was then that not only the likes of the men who signed the Declaration of Independence but people of all sorts began to talk to each other, making the great Jacksonian cacophony that Alexis de Tocqueville listened to with such wonderthough, finally, with less wonder than Seldes almost a century later.

Rolling carefully through forgotten testaments, manifestos, sermons, and propheciesquoting at length, sometimes for pages at a time Seldes emerged with drive, momentum, and in a hurry, leaving the reader in fright, dumfoundedness, and most of all suspense. Seldes was certain that simply to get onto the page the stories of such avatars of absolute salvation as the revivalist Charles Finney, the killer prophet Matthias, or the Perfect Communist John Humphrey Noyes; of camp meetings where men and women seeking union with God delivered themselves into madness; or of communities where educated people cultivated a common insanity as philosophically impregnable as it was genteel, would be to leave his readers shaking heads in disbeliefuntil, suddenly, their own familiar world loomed up with strange faces uttering even stranger demands, perhaps speaking in the same messianic tones the reader might have just heard and dismissed, and every politician or minister, every public voice of any sort, sounded like a doomed and beckoning figure from the past.

I came gradually to want to prove nothing. In the cadence of the sentence you can hear a New England shopkeeper returning an overcharge, in its balance one of Shakespeares kings admitting guilt: in the way the strength and foreshadowing of I came yields to the slowly declining syllables of gradually, hear the words almost come to a halt with the hurdles of to want to prove, only to come back, with the listener now barely paying attention, with the hard, blunt no of nothing. It is a cant-destroying voiceand it drives Seldes all across a country and a time so bent on the impossible that one can forget that the people one meets in his pages were true heirs of Franklin, Adams, Jefferson, Hamilton, Madison, walking in their footsteps, founding their own nations on a farm in Vermont, by the banks of a river in Kentucky, within the walls of a town house in New York. There is now a certain opportunity, wrote a founder of a new America in 1843an America called Fruitlands, not far from Concord, Massachusetts, a new nation consisting of barely a dozen adults and four or five children, which lasted less than a yearfor planting a love colony which may be felt for many generations and more than felt; it may be the beginning of a state of things which shall far transcend itself. That in a very few words catches the story told in