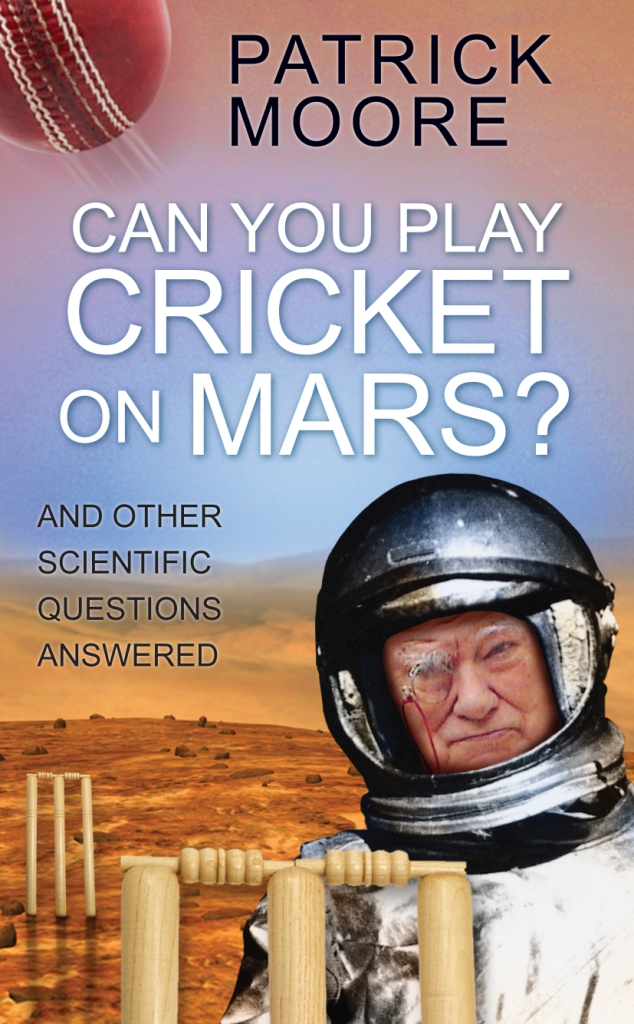

CAN YOU PLAY

CRICKET

ON MARS?

CAN YOU PLAY

CRICKET

ON MARS?

AND OTHER SCIENTIFIC

QUESTIONS ANSWERED

PATRICK MOORE

First published in 2008

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

Patrick Moore, 2008, 2012

The right of Patrick Moore, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6941 6

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 6942 3

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

INTRODUCTION

This is a book of question and answer. I will ask the questions, and do my best to give the answers. But at the very outset, I think it may be useful to give a brief rundown of the various components of the universe, introducing terms which will crop up time and time again.

The Earth on which we live is a planet, moving round the Sun in a period of one year. It is not the only one in the Suns family; there are seven others, and these are the main members of the Solar System. A planet has no light of its own, and shines only by reflected sunlight. Most of the planets have secondary bodies or satellites moving round them; we have one satellite, the Moon, which also shines by reflected sunlight. The largest planets, Jupiter and Saturn, have over sixty satellites each, though most of them are very small.

Reckoning outward from the Sun, we come first to rocky, comparatively small planets: Mercury, Venus, the Earth and Mars. Then comes a wide gap, in which move thousands of small bodies known as asteroids. Beyond the asteroid belt come the four giant planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, with their satellite families; the giants are not rocky, but have gaseous surfaces. Beyond the path (orbit) of Neptune lies another swarm of smaller bodies, making up the Kuiper Belt; the largest members of which are Eris and Pluto. Pluto, the first member of the swarm to be discovered (in 1930) was long classed as a planet, but has now been officially relegated to the status of an ordinary Kuiper Belt Object or KBO.

Comets also move round the Sun, but while the orbits of the planets are reasonably circular those of most comets are very elongated. At its closest point to the Sun (perihelion) a comet is very close to the solar surface; at its furthest (aphelion) it may be far beyond Neptune and the Kuiper Belt. A comet is not a substantial, solid body like a planet; the head, usually only a few miles across, is composed of ice and rubble, sometimes likened to a dirty iceball. Extending from it there may be a tail or tails, made up of dust particles or very tenuous gas. As a comet moves it leaves a dusty trail behind it; if one of these particles enters the Earths atmosphere it will be heated by friction against the air particles and will burn up, producing a shooting star or meteor. A meteor will burn away at around forty miles above sea level, but a larger body may survive to reach the ground, and is then called a meteorite. Note that meteorites come from the asteroid belt, and are not associated with either comets or shooting star meteors.

The Sun is a star, shining by its own power; the surface is hot (over 5,000 degrees celsius) and the core has a temperature of about fifteen million degrees. The Sun is not burning in the manner of a coal fire; its energy is due to nuclear reactions going on deep inside it. It has been said that it is a vast, controlled atom bomb! It is indeed vast when compared with our world; you could cram a million Earths inside the Sun and still have room to spare. It is ninety-three million miles away, but in our sky it looks the same size as the Moon, which is much smaller than the Earth but is only about a quarter of a million miles from us.

Every star is a sun, shining by its own light. Some stars are less powerful than the Sun but we also know of stars which have well over a million times the Suns luminosity. They look so much smaller and fainter than the Sun only because they are so much further away; the nearest star beyond the Sun is roughly twenty-four million million miles away. For distances of this kind, units such as the mile or the kilometre are inconveniently short (just as it would be clumsy to give the distance between London and Manchester in inches) and a different unit is preferable. Light does not travel instantaneously; it flashes along at 186,000 miles per second, so that in one year it crosses almost six million million miles. This distance is known as the light-year. The nearest star beyond the Sun is just over four light-years away.

The stars are so far away that their individual or proper motions are too slight to be noticed except over very long periods; the star patterns or constellations look virtually the same now as they must have done in the time of the Trojan War it is only our near neighbours, the members of the Solar System, that move perceptibly from night to night. The constellations have been given attractive names, many of them mythological Orion, Cassiopeia, Perseus and so on but the stars in a constellation lie at different distances from us, and have no real connection with each other; we are dealing with nothing more than a line of sight, and the names mean nothing at all. We use the old Greek system, but the ancient Chinese and Egyptians used different constellation patterns and names.

The Sun is one of about 100,000 million suns making up our star system or Galaxy. Many of the stars have planets of their own, though as yet we have been unable to see them directly (except in a couple of rather dubious cases), and have had to locate them by indirect methods. The Galaxy is a flattened system, measuring 100,000 light-years from one side to the other; the Sun lies near the main plane, about 26,000 light-years from the centre. When we look along the main plane we see many stars in the same direction, and this causes the appearance of the Milky Way. The stars in the Milky Way are not really crowded together, and are in no danger of colliding; we are merely dealing with another line of sight effect.

As well as its individual stars, the Galaxy contains huge clouds of gas and dust called nebulae, inside which new stars are being formed from interstellar material. If a nebula is illuminated by a convenient star, it shines; if not, it is a dark mass detectable because it blocks the light from objects beyond it.

Our Galaxy is not the only one; we can see others millions, hundreds of millions or even thousands of millions of light years from us. Galaxies tend to form groups or clusters; the Sun is a member of one such group (the Local Group). Each group of galaxies is receding from each other group, so that the entire universe is expanding and the faster away they are, the faster they are receding. With modern instruments we can probe out to more than thirteen thousand million light-years.