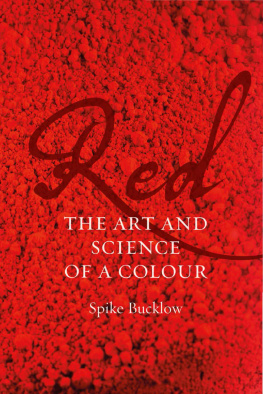

THE MOST RENOWNED PAINTERS used only four colours to paint their worksEven so, each picture sold for the price of a whole town. Now, when purple finds its way onto the walls of rooms and when India furnishes the mud of her rivers and the gore of her snakes and elephants, there is no first-rate paintingpeople nowadays value materials above genius.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book developed from lectures given at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, Fitzwilliam Museum and University of Cambridge International Summer Schools. Thanks are due to Sarah Ormrod and all her students (especially the class of 08 Maria Jos Arjona Peris, Leslie Barr, Karen Crane, Moira Feinsilver, Iris Hoogendoorn, Alexandra Karagianni and Estella Rizzin). Thanks are also due to Institute students and interns, too numerous to mention by name. Some of the ideas were first aired in Zeitschrift fr Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung , 99, 00 and 01. The idea for a book came from Tiana Dougherty, its final shape owes much to Clare Osdene Shapiro, Catheryn Kilgarriff, Rebecca Gillieron and especially Kit Maude.

I would like to thank the following for their encouragement, support and patience; Juan Acevedo, Linton Bocock and the Mold Room, Hilary Bourdillon, Ruth Hart Brown, Sarah Burwood, Jo Dillon, Rupert Featherstone, Alison Fell, Eike Friedrich, Marianne Fitzgerald-Klein, Kate Fletcher, Nicholas Friend, Helen Glanville, Christopher de Hamel, Andrea Kirkham, Andria Laws, Maria Madrid, Ian McClure, M.A. Michael, Doug Mollard, David Oldfield, Stella Panayotova, Patricia Salazar, Pamela Smith, Wolfgang Smith, Francis Sword, Ferdinand Werner, Mandy Worrall, Renate Woudhuysen and Lucy Wrapson. Most of all, I wish to thank my family.

Dedicated to the memory of Dr Martin Lings (19092005)

FOREWORD BY DR PAMELA TUDOR-CRAIG, LADY WEDGWOOD

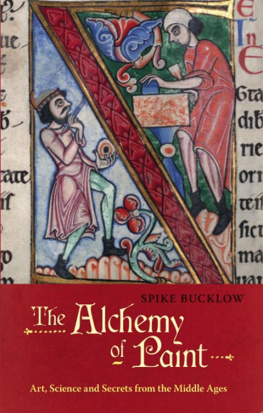

This is a dazzling book. If the mysteries of alchemy appeal to you, it is a necessity. If you use paints, you must struggle with it, even to the point of considering some of the recipes. Improbable though many of them are, Bucklow has tried them and testifies that they can work. The science behind them is unlike ours. He reckons most of it is five thousand years old. He admits that the distinction between it and magic is foggy, but this science is convergent, unifying, and magic scatters, disperses. This science is based on the properties of the four elements, which can intermingle if they have concordant qualities, but not if they present contrasting qualities to one another. In these pages there is a litany of precious pigments and how medieval artists refined them. He goes from Tyrian purple, extracted from a gland in Murex snails, and scarlet from pregnant beetles clinging to oak trees, to ultramarine from lapis lazuli, through vermilion, to dragonsblood, which does not issue from a battle to the death between a dragon and an elephant, but is a mastic. On p.173 we come to gold, and from that point the narrative becomes totally compelling. Bucklow argues cogently that the value we still attach to gold is based not on rarity or even beauty, but on the property, appreciated in the centuries of faiths, of indestructibility. It cannot be destroyed by fire or by liquids. It has been endlessly recycled. It is the nearest thing on this earth to immortality.

This takes us to what the author calls The Other Side, the inner meaning of this alternative science. Now he begins again with the Virgins robe, of pure white wool dyed Tyrian purple, which was taken in the 7 th century to Hagia Sophia, and its symbolic significance. This purple is originally pale yellow, which darkens to purple with exposure to the sun, but does not subsequently fade in sunlight. So the robe is richly symbolic. From there he explores the mythology around vermilion, returning again to the supremacy of gold. Unlike other substances essential to pigments, gold has been found almost everywhere (in Wales, for instance, before the Romans). At this moment in a climate of dwindling values, gold has once more asserted its supremacy. Perhaps our financiers should read this book. What about a new gold standard?

Along the extraordinary path which Spike Bucklow has carved through the intricacies of alchemy he has encountered the mystic Walter Hilton, and the medieval philosopher and scientist Albertus Magnus, whose many tomes included a lapidary. He has drawn upon Dante and Shakespeare, Achilles, Persephone and Pluto, Plato and Aristotle. He pays tribute to the prodigious Islamic contribution. The late 13 th century lapidary of Alphonso X of Spain contained a recipe for making golden stained glass. Golden stained glass immediately became the vogue right across Europe. Rich mines for silver were exploited in the Harz mountains, in the 10 th century and in the 11 th and 12 th centuries in Austria and the Tirol. By the 13 th century. European silver was mostly exhausted. So now I understand why the greatest Bibles of the 10 th and 11 th centuries used so much silver. How lovely they must have looked, but now alas

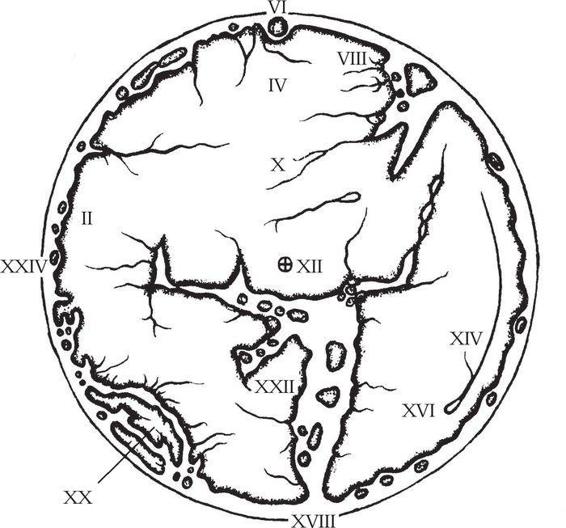

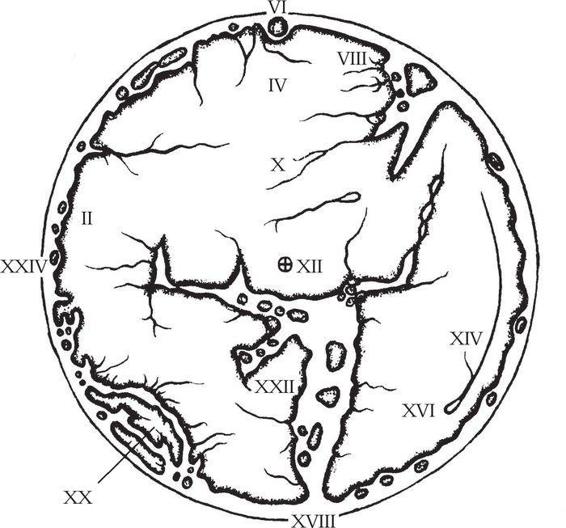

You will find here the explanation for the globes divided by a T-cross which are almost ubiquitous in the hand of a Medieval Christ in Majesty: the vertical bar is the Mediterranean separating Europe from Africa, with Europe to left. The horizontal bar, formed by the Nile and the Don, divides Africa and Europe from Asia. The partitions represent the apportioning of the world between Noahs three sons.

This book is a treasure house of knowledge, some of it originally deliberately obscured, like the secrets of the Masons. I am convinced the knowledge was passed from master to pupil through apprenticeship, and that it would have been almost impossible to follow the recipes from a book until you had already learnt them through practical experience and from a practitioner. The almost bewildering range of reference so ably handled here reflects the Medieval world view, which saw all knowledge as ultimately one.

Every scribe who is instructed into the kingdom of heaven is like a householder who brings out of his storeroom things both new and old. Matthew 13:52. Spike Bucklow is such a scribe.

Schematic of the Hereford mappa mundi (c.1300) with selected features of the Old World.

KEY

| II | Griffin |

| IV | Afghanistan |

| VI | Paradise |

| VIII | Elephant |

| X | Tower of Babel |

| XII | Jerusalem |

| XIV | Basilisk |

| XVI | Gold-digging Ants |

| XVIII | Pillars of Hercules |

| XX | Hereford |

| XXII | Rome |

| XXIV | North Pole |

PREFACE

As a scientist working in the art world, I spend time balancing value systems that are sometimes in competition. Of course, both science and art have more than one value some scientific endeavours are valued for their contribution to knowledge, and others, for their utility. Art has innumerable values. For example, as a conservation scientist, when dealing with the physical nature of works of art, I try and reconcile arts historical and aesthetic values when the venerable signs of age may impede the objects intended function as a work of beauty.