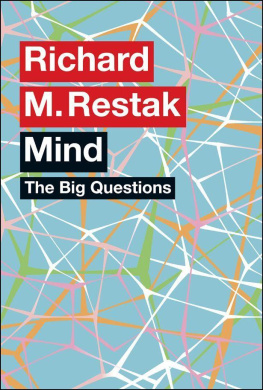

THE BIG QUESTIONS

Mind

Richard M. Restak is a practising neurologist and former president of the American Neuropsychiatric Association.

Author of nearly 20 books, including several New York Times bestsellers, he has received widespread acclaim for his incisive and accessible treatment of this complex topic. He is currently Clinical Professor of Neurology at George Washington Hospital University, and maintains a private practice in in neurology and neuropsychiatry in Washington, DC.

The Big Questions confronts the fundamental problems of science and philosophy that have perplexed enquiring minds throughout history, and provides and explains the answers of our greatest thinkers. This ambitious series is a unique, accessible and concise distillation of humanitys best ideas.

Series editor Simon Blackburn is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge, Research Professor of Philosophy at the University of North Carolina and one of the most distinguished philosophers of our day.

Titles in The Big Questions series include:

PHILOSOPHY

PHYSICS

THE UNIVERSE

MATHEMATICS

GOD

EVOLUTION

MIND

ETHICS

THE BIG QUESTIONS

Mind

Richard M. Restak

SERIES EDITOR

Simon Blackburn

Contents

Are we creatures of pure thought?

The development of the human brain

Achieving the highest levels of brain performance

Seeing things as we are

Problems of identity and awareness

Looking under the hood

The secrets of body language

The quintessential identity problem

Does our brain already know what were going to do?

Putting our minds to work

The pleasures and perils of mind wandering

The dangers of multitasking and thought suppression

What do we know and how do we know that we know it?

Processing the past and the future

Seeing ourselves in others

Addiction, pure sex, evolutionary necessity or a beautiful relationship?

Fury and the frontal lobes

Random noise or vital insight into the unconscious?

Illusion, reality and the mind

Thinking in new and different ways

INTRODUCTION

The mind what it is, how it works has long exerted a fascination, and dedicated thinkers since the early philosophers have wracked their brains over it. In fact, therein lies an enduring Big Question. Is the brain the same as the mind? And following on from that, if we cannot look at our mind or our brain without employing them as instruments of our exploration do we risk invalidating our investigation? The paradox of self-reference hovers over attempts to understand the mind.

There are other ways of formulating this paradox, but at the core of it is a question about identity, a sense of an I. In the history of thought, the mind has, along with the brain and the soul, formed a triad of ways to understand the essence of a person. Once of vital importance to philosophers, the soul is now largely the province of theology and religion; the brain, by contrast, has entered common parlance comparatively recently, while mind endures in both everyday language (keep it in mind, mind your manners, hes losing his mind) and remains suggestive of higher purposes reflection, intellect, imagination. Philosophers and anatomists witness Descartes or Leonardo da Vinci could, if not always accurately, attempt to delineate connections between motor functions, the senses and the brain. On the other hand, there is not much poetry associated with the brain and a very great deal with the mind.

Today, with the advance of science, the brain edges into the limelight, its status enhanced as new discoveries about its structures and operations emerge. Computer science suggests a metaphor, whereby the brain may be the hardware and the mind its software. Reducing the metaphor to its simplest form produces an equation: mind = all the things a brain does.

While I too have made such claims in several of my earlier books, Im now less certain of that equivalence. For one thing, the word mind can be a collective attitude or Zeitgeist, as in the mind of a nation. Further insights into this mind-writ-large view have been achieved thanks to technology. The Internet now makes it possible to gather real-time data on the activity patterns and verbal and written expressions of millions of people, confirming that a person may have a different mind to say or do something when part of a group than when in isolation. This is one of the reasons behavioural predictions, about individuals or groups, are so difficult to make. Sometimes collective actions both positive and negative may be unimaginable to the individual minds comprising the group. It is difficult to account for this solely in terms of brain activity and neuroscience in its present form.

In addressing Big Questions about the mind, the sense of self-referentiality is never far from the surface. We cannot ask What is thinking? without thinking about it. We cannot ponder What is knowledge without reflecting on the thought processes that we use in order to acquire much of our knowledge. However, in tackling such questions there is a choice: whether to regard it as primarily a philosophical enquiry, or whether it is a scientific enquiry. My approach is to tend towards the latter. In the 21st century few would argue that memories and emotions, words and ideas, dreams and imagination, perceptions and thoughts, and a sense of self and of the outside world are not activities of the brain. We often recognise this most clearly in their absence, by what we see when there are interferences with the normal workings of the brain. And today we are not simply relying on our own self-referring minds to consider these issues brain imaging, cognitive studies, precise anatomical studies, chemistry and many other investigative modes are playing a role. To put it another way, while, philosophically, the self-referential paradox remains, there are practical ways in which we can step outside of ourselves to help tackle the Big Questions.

In approaching the questions posed in the chapters that follow, I have not aimed at definitive answers; in many instances there are no single answers. I have sometimes taken an authors privilege of emphasizing answers that I personally favour, but in doing so I dont expect that my responses will meet with universal agreement. My purpose is to entice the reader to assume an active role in exploring and thinking to use my responses as a spur to coming up with their own responses to the 20 Big Questions. If Ive achieved my purpose, readers will be persuaded to assume the role of good jurors who, after examining the evidence, reach their own conclusions, while retaining full awareness that other people might come to different conclusions.

Richard Restak

Washington, DC, USA

Morell, Prince Edward Island, Canada

CAN WE HAVE A MIND WITHOUT A BODY?

Are we creatures of pure thought?

Think back to the last time you had a bad case of flu. Alongside the fever and aching body, you werent able to think very clearly, were you? If you tried to read a book or do any work you couldnt concentrate on it. In such a state, you would be unlikely to believe that the mind can be considered separate from the body the flu was affecting both your mind and your body.

Neuroscientists speak of embodied cognition as a shorthand for the linkage of all aspects of our mental lives to our bodily experiences. The ancients had an inkling of this mindbody dependence. They postulated different personality types based on the prevailing influence of the four physical elements of air, fire, earth and water and their respective qualities of dryness, warmth, cold and moisture. Later theories associated air, fire, earth and water with yellow bile, blood, phlegm and black bile. Diseases were believed to be due to an imbalance of one or more of these four bodily humours, with humoral theory inspiring one of the earliest methods for personality assessment. We still employ humoral terms in describing peoples personalities. Short-tempered people are choleric, pessimistic types bilious, confident individuals sanguine and apathetic folk phlegmatic.

Next page