THE BIG QUESTIONS Philosophy

Simon Blackburn is Professor of Philosophy

at the University of Cambridge, Research

Professor of Philosophy at the University of

North Carolina and one of the most

distinguished philosophers of our day.

He is the author of the bestselling books

The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, Think,

Being Good, Lust, Truth: A Guide for the

Perplexed and How to Read Hume.

The Big Questions confronts the fundamental

problems of science and philosophy that have

perplexed inquiring minds throughout history, and

provides and explains the answers of our greatest

thinkers. This ambitious series is a unique, accessible

and concise distillation of humanitys best ideas.

Titles in The Big Questions series include:

PHILOSOPHY

PHYSICS

UNIVERSE

MATHEMATICS

THE BIG QUESTIONS

Philosophy

Simon Blackburn

Contents

Preface

The twenty questions I have chosen here are among those that often occur to thoughtful men, women and children. They seem to arise naturally, without powers of reflection. We want to know the answers. Yet philosophy is unusual among academic disciplines in appearing to cherish the questions rather than provide the answers. The tradition contains few agreed and definitive solutions. This may be a matter of regret or embarrassment to those of us who work as academic philosophers, but I do not think it should be. This is partly because some questions which appear simple and straightforward at first glance fragment into many other little questions on reflection. We ask, Why be moral? or What is the meaning of life? as if one answer might be around the corner. But perhaps there are many different questions. Why be moral in this particular way on this particular occasion, faced with this, that or the other temptation? Which of the things that can interest and engage people deserve to do so? There will be many answers in different contexts, rather than one big answer, and it is progress to realize this.

Other questions may have different concealed traps in them. Why is there something rather than nothing? is a good example. Although it is sometimes thought to be the fundamental question of philosophy, the deepest question anyone can ask, it may be that its depth, and the obsessive interest it can engender, are the artifact of a logical trick ensuring that it is unanswerable. Or perhaps not: these are matters on which we have to tread carefully, and not all thinkers will tread the same path. I do not think we should lament that or be embarrassed about that. We would not all tread the same path if we tried to write essays about almost any human affairs: just imagine the different lights in which a political decision or a family holiday (or family quarrel) may appear to different participants and observers. Shakespeare wrote wonderful plays about love, war, fear, ambition and many other things, but nobody believes that he gave definitive answers or that there is nothing left to add.

So I have tried to acquaint the reader with the questions, with some of the things that get said, and with some of the pitfalls and perplexities surrounding them.

The twenty questions I have chosen are here arranged in no particular order, except for the last one, which comes last for all of us. The discussions are intended to be self-contained, and therefore readers are welcome to dip in wherever they wish. Since there are occasional cross-references, they may find themselves drawn backward or forward as the case may be, and I hope that they are.

The 21st century continues a trend also visible in the last century. This is a certain kind of scientific triumphalism. The euphoria that came with cracking the human genome, and the dazzling prospects of unlimited biological and medical progress that this encouraged, have contributed to an atmosphere in which humane studies like philosophy are put on the defensive. Insofar as we philosophers do things like interpreting human nature, then is philosophy itself due for retirement, overtaken and superseded by the juggernaut of advancing science? In a number of chapters I reflect on the actual achievements and promises of the new sciences of human nature, not always with quite the confidence that others seem to feel. I hope that the reasons in play at least raise some doubts, and enable others to approach the difficult problems of how we do think and feel, and then how we ought to think and feel, with proper respect.

I owe thanks to my agent, Catherine Clarke, and to my editor at Quercus, Wayne Davies, for unfailing encouragement. I owe thanks, as ever, to my wife whose editorial and literary help have been invaluable. The University of Cambridge granted me a sabbatical term in 2008 which gave me the leisure to write many of the following chapters, while the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill provided a research chair from which to work, and I am most grateful to both institutions.

AM I A GHOST IN A MACHINE?

The search for consciousness

Everyone knows that we are creatures of flesh and blood. Included in the flesh is a nice big brain, an unimaginably complex assemblage of some hundred billion neurons or brain cells, each with around a thousand connections with others: many trillions of connections in all.

The human brain controls memory, vision, learning, thought and voluntary behavior. It also monitors and plays a part in controlling the involuntary behavior and the autonomic activities of our organic support systems. Different sense organs respond to physical stimuli, and thence transmit signals to dedicated parts of the brain, which then work together to enable us to see, feel, taste, smell, remember and compare and classify things. Most of the time it all works magically well, and we only get a sense of its wonderfully fragile nature when things go wrong. A small amount of neuronal damage, and we have people who think that the person in the mirror is not themselves but someone different, or who cannot remember who or where they are, or who think their wife is a hat. A small shadow on a scan, and Alzheimers terrifyingly awaits a great many of us.

The inner world

This is the physical basis of our lives as conscious, thinking, active animals. But there is a temptation to think: thats fine as a basis, but then what? What is it the basis of? We could chase, say, an optical stimulation from the time a light ray hits our eyes, on to a pattern of activation of cells in the retina, on to excitations in the optic nerve, back into increased activity in the visual cortex, and thence, perhaps, into a diffusion of excitements across different parts of the entire system. But where in all this is the fact of me, say, seeing a car passing? How does the conscious experience arise or emerge from the fantastic physical system? And in our imaginings there is then a kind of secondary, superadded world. This is the world of our inner experience, our imaginings, feelings, thoughts and sense experiences: our own private take on things.

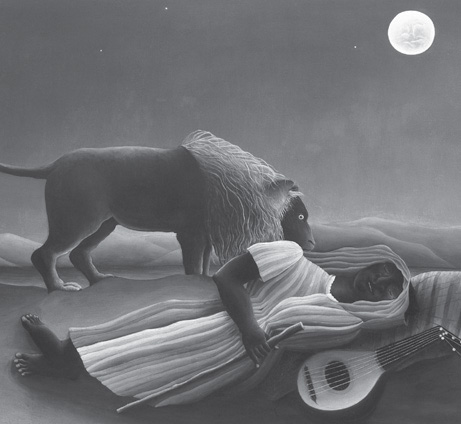

THE SLEEPING GYPSY (1897)

Henri Rousseau (18441910)

We go on to think that my inner world is accessible to me and yours is accessible to you. But yours is not accessible to me, or not in the same way that it is to you or that mine is to me. We have privileged access to our own mental states. You, as scientist, might be able to chart the excitation patterns in my brain. But it is I, the subject, who sees the car passing. And you do not see my sight of that, however closely you pry into my brain, or however accurately you plot the way the cells are doing their dance. Our mental states are themselves invisible to the best sciences of the brain. Suppose I think about the boulevards of Paris, pleasurably laying them out in my minds eye as I imagine strolling down them. The neurophysiologist, however far he probes, will not be able to hold up a fragment of brain and say, Aha! Here we have a thought about the boulevards of Paris! For, alas, the brain is gray but in my thoughts the boulevards are brightly colored. The bit of brain is small, but the boulevards are long and wide. The brain is soft tissue, while in my daydream the boulevards are hard pavement, and with traffic on them.