The heavens rejoice in motion

JOHN DONNE, ELEGIES (CA. 1590)

W e are embedded in a magical matrix of continuous motion. Clouds change shape, tsunamis destroy cities. Natures animation happens eternally. Its energy springs from no apparent source. Nor, we learn, does it ever diminish. Its tireless.

As we have with all magic, weve grown accustomed to natures endless guises. Too accustomed; we scarcely give it a second thought. Yet it is intimately close. Even the workings of our eyes and brains, reading these words, are examples of natural motion. In our minds case its the action of electrons and neurons as one hundred millivolts of electricity make various connections in the brains one hundred trillion synapses. The result: our perceptions.

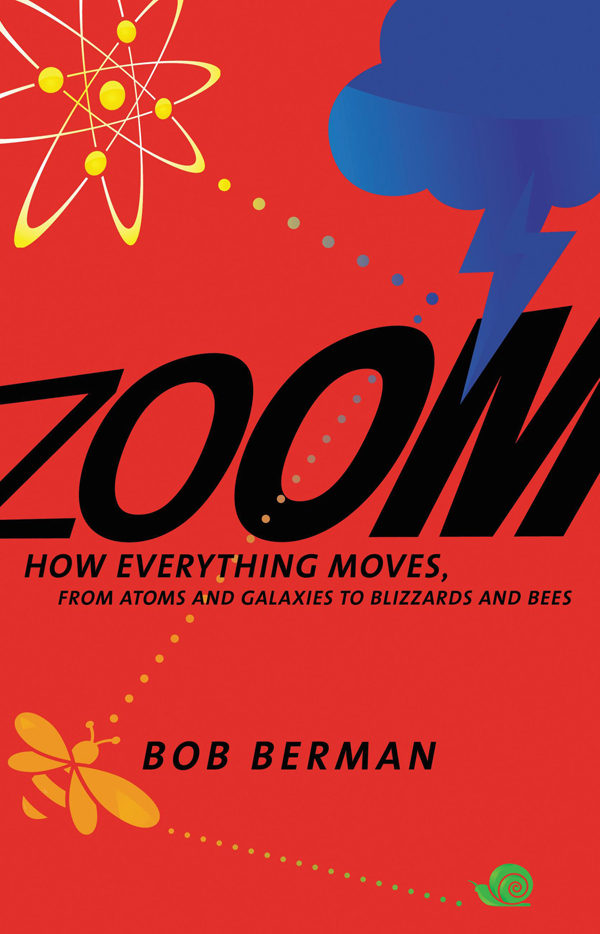

This book, then, is about natural activity in all its forms. It is essentially a book of miracles. To paint this dynamism in the vivid colors it deserves, I will offer close-up peeks at the most fantastic, epic, intriguing, but also little-known ways in which spontaneous action operates, using the discoveries of scientists from ancient times to the twenty-first century.

Because motion is everywhere and takes all forms, this cannot possibly be an exhaustive survey, though I have endeavored to include all natures major theaters, such as wind, digestion, and shifting poles.

A mere dry recital of facts and data wouldnt be much fun. So lets marvelnot at man-made motion, even if our rockets and bullet trains are indeed wonderful, but at the kind that unfolds on its own. This book itself moves, too, after the opening high-speed salvo, from the slowest entities to the fastest ones. Along the way Ive paused to recount the stories of some of the fascinating people who brought us discoveries in various venues. Some were geniuses. Others were lucky. Many were so far ahead of their time they were ridiculed.

This, then, is our storyof the endless movements that forever surround us and the brilliant people who uncovered these revelations through the centuries. And how destinys own quirky momentum carried them through their lives.

Bob Berman

Willow, New York

Its a warm wind, the west wind, full of birds cries

JOHN MASEFIELD, THE WEST WIND (1902)

T he storm was scary-wild.

Although it had lost hurricane strength before slamming into upstate New York, the wind still howled at fifty-five miles per hour, and the dog hid under the bed. But it was the rain, the relentless rain, that had us all worried. By the second day, more than eight inches had fallen. In our mountainous area, streams overflowed before the first sunrise. Many wooden spans, along with two steel-and-concrete bridges, did not survive the night. They were simply gone, vanished without a trace. Authorities later assumed they must be lying at the bottom of the enormous reservoir twenty miles downstream.

Entire communities were isolated from the world. At noon that day, some homes, those still inhabiting their footprints, had water up to their windowsills. Meanwhile the ground had become so soft and wet that the gales had no trouble knocking down swaths of trees, root balls and all.

The power went out the first night. In our rural region, which doesnt offer mail delivery or cell-phone service even on the sunniest days, we were utterly alone. No one had water, plumbing, or telephones. It might as well have been the year 1500.

Morning dawned to find trees across my roof. Shattered glass littered the stone entranceway. But this wind-borne destruction paled next to the devastation wrought by the waters moving through those valleys. My niece lost her entire house. It had been standing placidly for forty years, and then it was gone. The floodwaters had been five feet deep and had crept along at less than four miles per hour. Yet this sluggish brown water had created far more devastation than my own backyards fifty-five-mile-per-hour gales.

It was ironic, in a way. For decades I had made my living narrating natures activity as though I were a sportscaster. As the astronomy editor of the Old Farmers Almanac and a columnist for Discover and then Astronomy magazines, I would routinely calculate how the moon and planets moved and describe their exuberant conjunctions. Natures motions reliably put bread on my table. Now they had turned on me. Like everyone else, I wondered how many out-of-pocket repair dollars I would have to spend.

If natures activity had long paid my mortgage and yet was now chasing me out of the house, I smelled a story whose dramas, tragicomedies, and linked biographies might equal any novels. I already knew that water moving at just four miles per hour is as destructive as a medium-strength tornado, which is why floods kill more people than windstorms. Water is eight hundred times denser than air and pushes things far more easily. But who were the first scientists to discover this? Were they impelled by personal events, as I was? Did their own lives and struggles include dramatic episodes?