The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To the women of my family

(in order of increasing distance from my word processor):

Marcy, Anjali, Alyssa, Jane, Rita, Paula, Lara, Dorianne, and Jessica

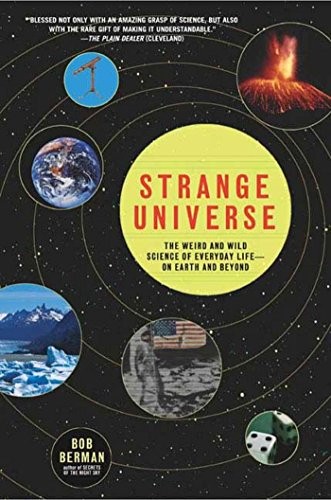

The basic realities of everyday existencelight and time and gravityare astounding if not downright mysterious. Commonplace facets of the physical universe that we experience without thought become magical, marvelous, and even preposterous upon reflection and examination.

Can something as ordinary as a shadow engage us? Consider: Why are tree shadows blue when cast upon snow? What time of every day does Earths own shadow hover vividly against the sky, ignored by virtually everyone?

Natures curiosities are everywhere. Doesnt it seem odd (as it did to the ancient Greeks) that the full moon looks flat as a dish, as if painted onto the heavens? It baffled moonwatchers through the ensuing centuriesuntil just recently, when the flat-moon riddle was solved.

The briefest inquiry into even ordinary substances can rivet the mind. Case in point: water. Its the most common compound in the cosmos. And yet in liquid form it exists in only one other place in the known universe. Given the tiny size of its molecule, water ought to be a gas at room temperature, yet it isnt, thanks to a single reality-altering quirk. And it absorbs red light but leaves blue and green alone, dyeing oceans turquoise. It slows light to 75 percent of its customary speed, making fish appear in phantom positions. Such unexpected consequences, paradoxes, and improbable truths await the Eureka! of our notice.

The strange objects, events, processes, and phenomena described here have been selected for their everyday familiarity. My goal is not to dumb down complexities or explain well-known oddities to the scientifically challenged, but rather to offer readers, teachers, and other professionals a harvest of fresh material to share with friends and students. Spanning a wide and random range, the subjects have been organized into two sections. The first embraces earthly peculiarities of our lives and our world: surprising historical lore, statistical peculiarities, unexamined events like Groundhog Day, the vagaries of gravity, the nature of light. The second looks at anomalies and mysteries beyond our planet, from previously unpublished blunders and antics of the U.S. and Russian space programs to the smells of space to the Big Bang itself.

A comprehensive, thorough exposition of the universes curiosities would require many thick volumes. The choice of topics is based on recent scientific revelations and my own sense of what is likely to fascinate readers. After three decades of teaching college science courses, and as a longtime columnist for Discover magazine and an editor and columnist for Astronomy magazine and the Old Farmers Almanac, Ive learned that the universe is as full of curveballs as it is of electrons. If Ive succeeded, the book follows that model, illuminating both minuscule and monumental realities as ordinary as a snowball and as strange as an apple seed that outweighs an aircraft carrier.

Ive sought to convey what Ive learned of things hilarious and horrendous, the goofs and the glories, the magnificent harmony and the significant chaosthe puzzles and patterns comprising our daily lives and our whirling world.

Join me in a rousing journey full of discoveries that I hope will make your day every day of your lifeas they have mine.

Only a glitch in the laws of chance can explain why all the major meteor showers arrive in a single twenty-week span. During the annual shooting-star fireworks that peak around August 12, October 21, November 18, December 13, and January 3, up to a hundred bits of cometary debris visibly slice through the air just above us every hour. But in early winter the displays end. For seven straight months, little more than sporadic pellets pepper the heavens. So if your personal paranoia extends all the way into space and your HMO doesnt cover you for meteor assault, youd assume its safe to relax until midsummer.

No such luck. History tells us that whenever a person, home, or property has suffered a close encounter of the clobbering kind its happened during non-shower periods. Which makes sense when you think about it. Except for December 13s Geminids, composed of sturdier asteroid fragments, every major shower is made of skimpy, apple-seed-size rubble from comets, lightweight material that burns to oblivion during its collision with our atmosphere. Only a dusty trail lingers like a Cheshire Cats smile after the intruder has gone to meteor heaven. Sporadics, however, can be made of anything and come from anywhere. They can be rocky asteroid fragments or even bits of the Moon or Mars. Many contain substantial amounts of iron or nickel, and depending on their speed and initial size, some of this hardy stuff makes it all the way to the ground.

Slowed and cooled by the thick lower atmosphere, meteors no longer incandesce as they approach the surface and are barely warm when they land. On August 31, 1991, one smashed into a lawn next to two boys in Noblesville, Indiana, who immediately picked it up and later described it as slightly warm to the touch. In fact, meteors are not hot enough to glow once theyve dipped below fifty miles in altitude, having decelerated dramatically from their original fierce speed of twelve to forty-five miles per second down to anywhere from a twentieth to half a mile per second. But thats still fast enough to cause trouble.

Discover magazines Risk issue (May 1996) presented statistical evidence that were each six times more likely to die from a meteor impact than in an airliner crash. The reason: The post-impact effects of a meteor a few miles wide can wipe out most or all of the human race, while relatively few of us will ever be crash victims.

Virtually all meteors that land or airburst produce some damage, even if they dont remotely compare to monsters that come in on longer time scales and prompt serious philosophical questions about the general stability of the solar system. The most famous such humongous impact destroyed half the life-forms of Earth 65 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous period and the dawn of the Tertiary eraknown familiarly to geologists and meteor buffs as the K-T boundary. The resulting undersea crater, some 120 miles across and located just off Mexicos Yucatn peninsula, testifies to the amount of material blown skyward. It blackened the air for years, erased the dinosaurs as thoroughly as a studios special-effects department, and allowed us mammals to begin our spectacular evolutionary ascent toward rats and sitcoms.

A lesser known but far greater disaster happened 185 million years before that, at the end of the Permian period. In 2002, a team of geochemists led by Tokyo Universitys Kunio Kaiho uncovered convincing evidence that this greatest mass extinction of all time, which dwarfed the K-T event, destroyed 95 percent of all earthly species. Corroborating recent studies that examined trapped gases from sediments in various parts of the world, Kaiho discovered that the impact also converted solid sulfur into so much sulfur-rich gas that up to 40 percent of Earths atmosphere was consumed. The resulting frenzy of global acid production pickled the oceans and raised the acidity of the seas surface to that of lemon juice! Earth was nearly dealt a knockout blow. Plants and microscopic animals that had survived for a million centuries suddenly disappeared forever.