Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Mike Davis, a stirring correspondent and cherished friend, whose enthusiasm for things medievaleven (or especially) dark onesis the reason this book exists.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Full-color, high-resolution versions of the images can be found at www.saralipton.com.

INTRODUCTION: IN A MIRROR, DARKLY

CHAPTER ONE: MIRROR OF THE FATHERS: THE BIRTH OF A JEWISH ICONOGRAPHY, CA . 10151100

CHAPTER TWO: BLINDING LIGHT AND BLINKERED WITNESS, CA . 11001160

CHAPTER THREE: JEWISH EYES: LOVELESS LOOKING AND THE UNLOVELY CHRIST, CA. 11601220

CHAPTER FOUR: ALL THE WORLD A PICTURE: JEWS AND THE MIRROR OF SOCIETY, CA. 12201300

CHAPTER FIVE: THE JEWS FACE: FLESH, SIGHT, AND SOVEREIGNTY, CA. 12301350

CHAPTER SIX: WHERE ARE THE JEWISH WOMEN?

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE JEW IN THE CROWD: SURVEILLANCE AND CIVIC VISION, CA. 13501500

For now we see in a mirror, darkly; but then face to face. Now I know in part; but then shall I know fully, even as also I was fully known.

Paul of Tarsus, I Corinthians 13:12 (American Standard Version)

INTRODUCTION

IN A MIRROR, DARKLY

Thus indeed appear the Jews regarding the Holy Scripture they carry: like the face of a blind man in a mirror. By others he is seen; by himself, he is not seen.

Augustine of Hippo, Enarrationes in Psalmos 56, 9

For the first thousand years of the Christian era, there were no visible Jews in Western art. Manuscripts and monuments did depict Hebrew prophets, Israelite armies, and Judaic kings, but they were identifiable only by context, in no way singled out as different from other sages, soldiers, or kings. []

This story is quite well known. Finally, the vast majority of medieval Jewish images decorated artworks meant solely for Christian eyes, appeared in regions with few or no Jews, and were made by and for people (overwhelmingly monks, clerics, and secular leaders) who were far more interested in Christian society and worship than in Jewish people or practices. Simply labeling artists or patrons, or the general culture, as anti-Semitic tells us little about why these images were made or what they meant to the people who made and viewed them.

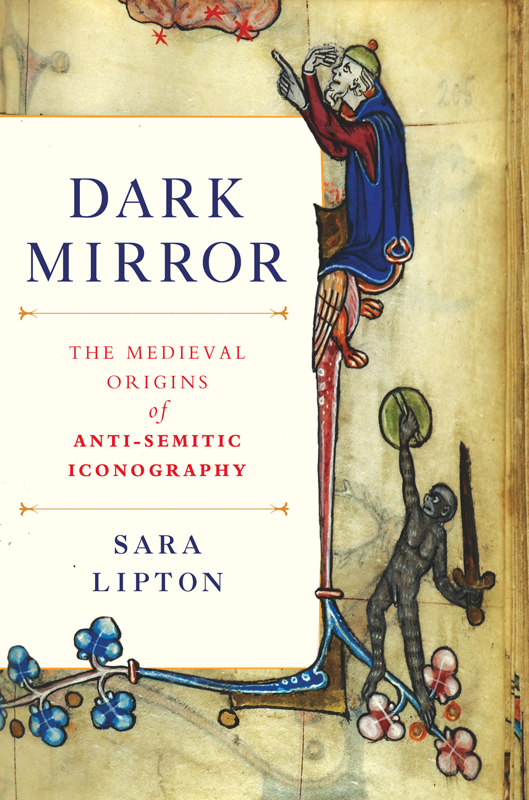

FIG. 1

FIG. 2

In this book, then, I take a different approach to medieval Christian depictions of Jews. My starting point is an observation I first made well over a decade ago: a remarkable number of these images highlight not only what the Jews look like but, even more, howand whetherthey see. It seemed clear that the new artistic emphasis on the Jew as viewer as well as image viewed was related to the traditional theological formulation of the Jews role in Christendom. Already in the letters of Saint Paul, who lamented that his recalcitrant coreligionists clung to the letter rather than the spirit of the law, the Jews were linked to the material, visible world and assumed to possess a purely carnal form of understanding.

The Jews sight would likewise preoccupy Augustine of Hippo (d. 430), the most influential of all early Christian writers on Jews and Judaism. For Augustine, Jewish-Christian difference was crystallized in their contrasting visual encounters with and reception of Christ: For truly how glorious is it, that he ascends to heaven, that he sits on the right hand of the Father? But we do not see this with our eyes, nor have we seen him hanging on the tree, nor have we beheld him rising from the grave. All this we hold in faith, we perceive with the eyes of the heart. We are praised, for we did not see, yet we believed. For the Jews too saw Christ. It is no great thing to see Christ with the eyes of the flesh, but it is great to believe in Christ with the eyes of the heart. , the contrast between the eyes of the flesh and the eyes of the heart will be a recurring theme in subsequent Christian writings about religious knowledge, revisited and sometimes reformulated as Christians modified their ideas about sensory perception.

Augustine added a significant new twist to Pauls denigration of Jewish vision: a stress on the uses of Jewish blindness and also on the Jews own visibility, that is, their physical presence. In several works, most notably the City of God , he wrote that the Jews primary functionand the reason they should be allowed to remain in Christian landswas to serve both as witnesses to and as living signs of Christian truth and triumph. The Jews did this in several ways. In preserving the ancient Hebrew text of scripture, Jews confirmed the authenticity of biblical prophesies about Christ (although they were blind to their true meaning). The Jews very bodies, sprung from the flesh of the ancient Judean deicides, were living proof of the historicity of the Crucifixion and their own peoples criminal role in it. The Jews defeat at the hands of the Romans and subsequent dispersal among the nations testified to their own error and to Christian triumph. Finally, at the end of days the Jews long-delayed conversion would herald Christs Second Coming.

According to Augustine, then, the Jews function in Christendom was to see (or rather, to see incompletely) and be seen ; that is, to bear witness in word, flesh, and status. The Jews failure to perceive God in Christ and to understand their own prophets, combined with their visible presence as exiled relics of an ancient and fallen people, testified to the verity of Christian faith.

For six hundred years after Augustines death, this conception of Jewish witness remained metaphorical, a largely literary abstraction unconnected to Jews actual visual practices or visual presence within Christendom. When early medieval theologians lambasted the Jews blindness, they were referring to their inability to correctly interpret and understand scripture rather than to their ocular encounter with Christ. When they discussed the Jews particular condition of servitude, they were referring to a theoretical status that was not markedly visible in the real world: Jews in the early Middle Ages were legally free and their lives were considerably more prosperous, secure, and comfortable than those of most Christian peasants. Only around the turn of the first millennium did Pauls insistence on Jewish blindness and Augustines conception of Jewish witness finally make their way into art. What brought about this new artistic focus on Jews looks and looking? What work did images of Jews do for the culture that created them?

A closer look at the role of sight in the thought of Paul and Augustine suggests a possible path toward answering these questions. As we have seen, both Paul and Augustine insisted that true Christians, unlike Jews, could believe without seeing. But this exaltation of pure, image-less faith did not negateindeed, it existed in some tension withthe fundamental fact of Christian history: Christ at one point took on flesh and walked the earth in full sight of his fellow men. God Incarnate was not an intangible Platonic form but a visible being. Throughout most of the New Testament there is consequently little denigration of bodily vision. Christ performed many visible miracles, and his disciples reveled in his physical presence. Though Paul decried the Jews carnal perception, he did not utterly dismiss bodily experience or the power of sight, glorying in having himself been granted a glimpse of the risen Christ. Likewise, though Augustine warned against the deceptive and seductive nature of physical vision, he conceded that physical sight could be religiously useful. Seeing suffering in the material world, for example, helped Christians to imagine the tortures of the Crucifixion and so to pity and love the crucified Christ.