LOVE AND LIBERATION

LOVE AND LIBERATION

Autobiographical Writings of the Tibetan Buddhist Visionary

SERA KHANDRO

SARAH H. JACOBY

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

A special thanks to the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation for crucial financial support for the publication of this book.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2014 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jacoby, Sarah, author.

Love and liberation : the autobiographical writings of the Tibetan visionary Sera Khandro / Sarah H. Jacoby.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-14768-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-51953-3 (electronic)

1. Bde-bai-rdo-rje, 18801929. 2. Buddhist womenChinaAmdo (Region)Biography. 3. Women religious leadersChinaAmdo (Region)Biography. I. Title.

BQ942.D427J33 2014

294.3'923092dc23

[B]

2013043777

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Jacket design: Jordan Wannemacher

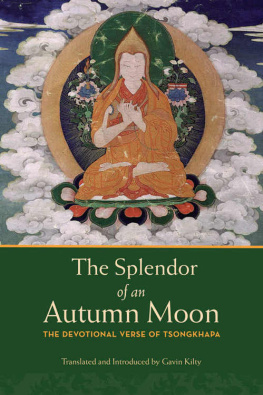

Jacket image: Sera Khandro scroll painting from the region of Gets Tralek Monastery in eastern Tibet, photograph of painting courtesy of Tralek Khenpo Tendzin zer

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

This book is dedicated to the lineage of Sera Khandro Knzang Dekyong Chnyi Wangmo, and to all the kins of Tibet whose voices we can no longer hear.

CONTENTS

THIS IS A BOOK about relationshipsbetween people and the land they inhabit, between religious seekers and the divine presences with whom they interact, between women and men dedicated to spiritual liberation, and between lover and beloved. The main protagonist in the stories and conversations that fill this book is the Tibetan female visionary Sera Khandro Knzang Dekyong Chnyi Wangmo (18921940). She would have described these relationships using the language of auspicious connections (rten brel), the matrix of conditions including specific times, places, and persons that must constellate in order for an individual cog in the larger wheel of life to accomplish her purpose.

Auspicious connections extend through space and time beyond the meaningful synergies bound within Sera Khandros texts, touching us here and now. In particular, specific auspicious connections have made this book possible; without them I could never have written it. The catalyst for this project came during my undergraduate years on a Tibetan Studies junior semester abroad program administered through the School for International Training. In Nepal while conducting fieldwork about Nyingma Buddhist laywomen, I had the good fortune to meet Semo Saraswati, who introduced me to her father, Jadrel Sangy Dorj Rinpoch (b. 1913), the seniormost living lineage master within the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism and also a direct disciple of Sera Khandro. Meeting Jadrel Rinpoch and his daughter would change the course of my life, but at the time, I could barely figure out how to offer him a ceremonial scarf (kha btags) properly, let alone understand his deeply resonant, Kham dialect-inflected Tibetan speech well enough to inquire about his extraordinary female guru.

After graduating from Yale College, I remained fascinated with Tibetan civilization, and dedicated myself to studying Tibetan language, religion, and culture both in Asia and in graduate school at the University of Virginias Department of Religious Studies. It took me five years of returning annually to visit Jadrel Rinpoch to gain the courage and the linguistic proficiency to ask him for permission to read his copy of Sera Khandros autobiography, which was unavailable elsewhere. During our conversations, Jadrel Rinpoch described Sera Khandro with the utmost reverence, telling me how she set the course of his future religious training when he first met her at the age of fourteen (fifteen in Tibetan years) in 1927. At this meeting Sera Khandro prophesied that his root lama would be Khenpo Ngawang Pelzang (Khenpo Ngakchung, 18791941) from Katok Monastery, prompting him to go straight there to study with him.

Receiving Jadrel Rinpochs permission and a copy of his manuscript set this project in motion, but the help of many other teachers and friends have made it possible to complete. In particular, Lama Tsondru Sangpo of Rangbul, India, aided me from the beginning, as did my friend Heidi Nevin, who was by my side in spirit and also sometimes in person through this story. Learning how to read Sera Khandros auto/biographical works, consisting of more than six hundred folios of cursive Tibetan handwriting filled with abbreviations and Golok colloquialisms from nearly a century ago, many unfindable in any dictionary, proved to be a major challenge. It was only through the kindness of Khenpo Sangy from Gyalrong (Khenpo Tupten Lodr Tay), who painstakingly read both Sera Khandros autobiography and later her biography of Drim zer with me over the course of several years and endless hours, that I understood anything of her writing. Khenpo Sangys insights into Tibetan language, idiom, and religion opened up a new world of thought for me. I will always be grateful for this enrichment, as well as for the congeniality and hospitality of all in the Gyalrong House in Boudhanath, Nepal, the site of our Sera Khandro reading marathons.

Auspicious connections sometimes operate in subtle forms and other times in dramatic ones. In the early days of 2002 I was staying at Jadrel Rinpochs monastery complex in Salbari, India, trying to figure out when and how to ask permission not just to read, but to translate and publish Sera Khandros autobiography (this study is the first part of the project; the full translation of her long autobiography will be the second). Jadrel Rinpoch is famous for his discretion in granting access to his precious manuscripts and teachings; I had good reason to fear making this request. In doubt, I phoned Lama Tsondru Sangpo in Rangbul, who urged me that I must go ahead and ask Jadrel Rinpoch everything that very day without fail. Later that afternoon, I found the right chance to speak with Rinpoch privately and received his blessing to accomplish these endeavors. The very next day, circumstances changed and access to private audiences with Jadrel Rinpoch was severely restricted, as it has remained to this day. Had I not followed Lama Tsondru-las advice, I might never have had the chance again.

Another dramatic auspicious connection electrified the possibilities for my research on Sera Khandro, this one beginning in the U.S. graduate school context and ending in eastern Tibet. My main dissertation adviser, David Germano, invited Alak Zenkar Rinpoch Tupten Nyima of Dartsedo, Tibet, to a symposium at the University of Virginia in the spring of 2004. David requested Zenkar Rinpoch to write me a letter of introduction for my upcoming research trip to eastern Tibet, where I planned to follow in Sera Khandros footsteps through the regions of Serta and Golok in which she lived. Several days of flights and dusty bus rides later, I ended up in the town of Serta knowing no one, armed only with my letter of introduction from Zenkar Rinpoch to a man he had identified only by first name, Khedrup. What to do? How to find the mystery man? In Sera Khandros day the treeless, rolling alpine grasslands dotted with yak herds and black nomads tents in the Washl Serta and Golok territories were infused with religious masters, but they were also dangerous places to travel without the proper local alliances. A century later, I found some of the same to be true as a foreign woman often traveling alone. Luckily Serta is small, and word gets out fast when an American is looking around an eastern Tibetan town for someone. Zenkar Rinpochs letter opened the door to Khedrup and Kyachungs hospitality and to many in the Serta community for me, without which my research would have been much more difficult.

Next page