The Philosophy of Qi

Translations from the Asian Classics

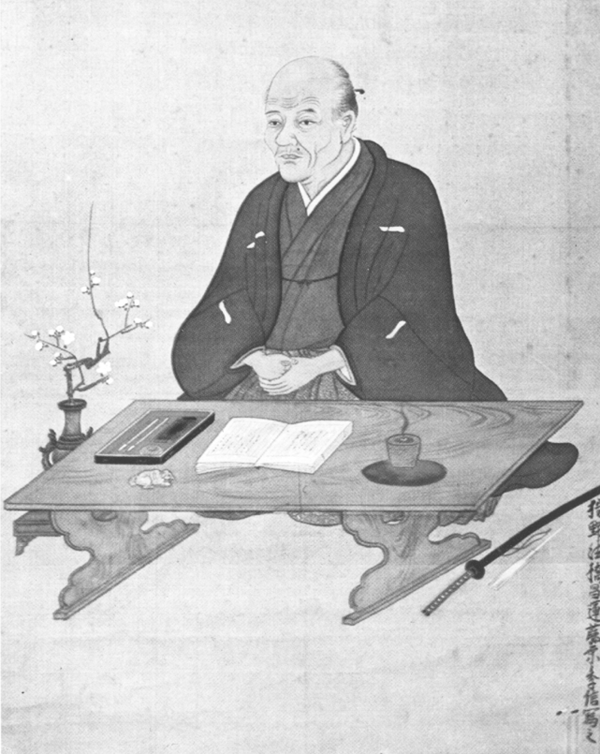

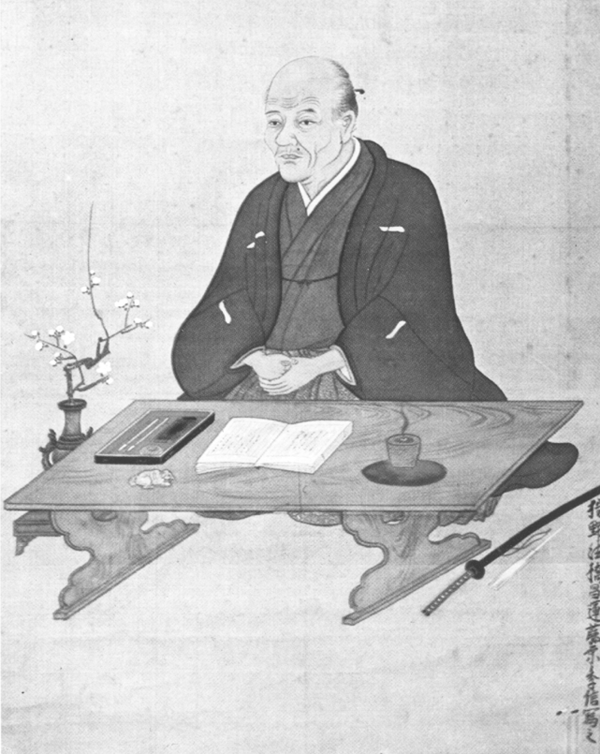

A portrait of Kaibara Ekken at age sixty-five, said to have been painted by the Kyoto artist Kano Shren.

The Philosophy of Qi

The Record of Great Doubts

KAIBARA EKKEN

TRANSLATED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY

MARY EVELYN TUCKER

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

Columbia University Press wishes to express its

appreciation for assistance given by the Thomas Berry

Foundation toward the cost of publishing this book.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2007 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-51129-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kaibara, Ekken, 16301714.

[Taigiroku. English]

The Philosophy of qi: the record of great doubts/Kaibara Ekken; translated, with an introduction, by Mary Evelyn Tucker.

p. cm.(Translations from the Asian classics)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-231-13922-5 (alk. paper)

ISBN 0-231-51129-9 (electronic)

1. Conduct of lifeEarly works to 1800. I. Tucker, Mary Evelyn. II. Title. III. Series.

B5244.K253T3513 2007

181'.12dc22

2006025278

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

To my parents,

Mary Elizabeth Hayes Tucker and William Duane Tucker, Jr.,

who supported me on the path of doubt and discovery

CONTENTS

This work has unfolded over two decades with the help of many people, to whom I am deeply grateful.

Among them are my teachers at Columbia University, Wm. Theodore de Bary, Wing-tsit Chan, and Irene Bloom, who set the standard for translations and commentaries that has shaped the field of Neo-Confucian studies. Their dedicated efforts to make the Neo-Confucian tradition understood and appreciated in the West have been unparalleled. Contributing significantly to these efforts has been the Confucian scholar Tu Weiming, Director of the Harvard Yenching Institute. Their comprehensive interpretive framework of Confucian humanism has influenced hundreds of students and scholars on both sides of the Pacific. Moreover, the tireless dedication of Ted de Bary and Tu Weiming as engaged intellectuals interpreting Confucianism and the challenges of modernity has been an inspiration to me and to countless others. Steadily behind so much of this work is Fanny de Bary.

I am also indebted to the Japanese scholars Okada Takehiko and Minamoto Ryen for their many years of encouragement of my study of Kaibara Ekken. Professor Okada welcomed me to his home on several occasions and provided me with copies of original documents of Ekkens writings. Watanabe Kimie accompanied me to visit Professor Okada, and her support of this work has meant more than I can say. She and her husband, Tatsuhiko, provided me with the woodblock prints of birds, fish, shells, leaves, and flowers from a nineteenth-century edition of Ekkens Plants of Japan (Yamato honz) that illustrate this book.

For answering questions regarding the translation, I am deeply grateful to Noriko Narita, Takako Noguchi, and Ron Guey Chu, whose generous assistance to so many can never be repaid.

In providing helpful evaluations of the manuscript to Columbia University Press, I am grateful to Janine Sawada, John Berthrong, John Tucker, and Tu Weiming. In assisting with pinyin romanization and preparation of the glossary, I am indebted to Deborah Sommers. Michael Ashby did a superb editing job, and Columbias staff has been most helpful, especially Jennifer Crewe, Juree Sondker, and Irene Pavitt.

Over many years, I have been grateful for the excellent secretarial assistance of Stephanie Snyder at Bucknell University and indispensable help from Ann Keeler Evans and Donna Rosenberg.

Thanks to Irene Blooms study of Luo Qinshun in China and Young-chan Ros book on Yi Yulgok in Korea, I was able to situate my work on Ekkens monism of qi in Japan in a historical lineage across East Asia. I am grateful to them and to colleagues in Japanese studies who have done path-breaking work on the Toku gawa period. These include Robert Bellah, Harold Bolitho, David Dilworth, Olof Lidin, Tetsuo Najita, Peter Nosco, Herman Ooms, Janine Sawada, and John Tucker. I have valued my conversations with Michael Kalton regarding Korean Confucianism and its contemporary relevance.

I would like to acknowledge with gratitude support from the Japan Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities to do the initial translation and the following foundations for their support in completing this work: V. Kann Rasmussen, Germeshausen, and Kendeda. Martin S. Kaplan and Nancy Klavans continue to be indispensable colleagues and invaluable companions in the journey toward a sustainable future.

Some of the ideas in this book were presented at conferences in Japan, Singapore, and Taiwan as well as at seminars at Columbia, Harvard, and Berkeley. I appreciated the comments and questions I received on those occasions.

Thomas Berry, John Grim, and Brian Swimme have provided incalculable moral support for this project. Their friendship over the years is a source of constant joy to me in the spirit of qi.

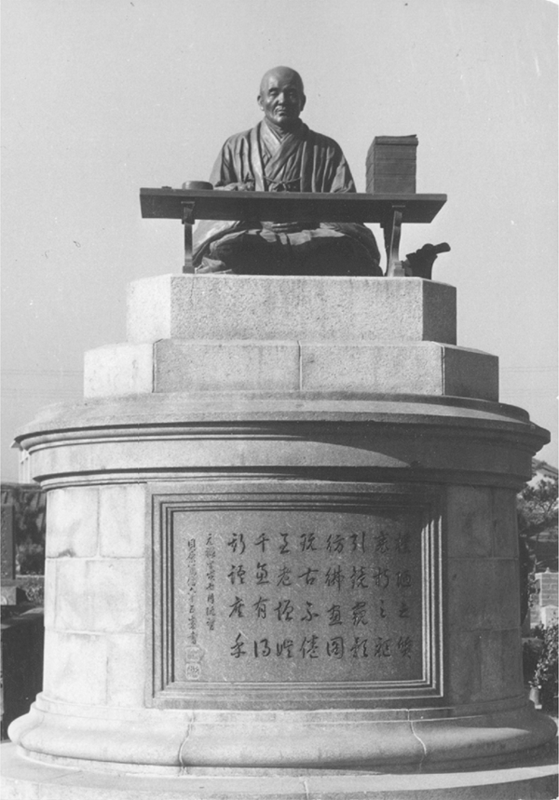

The statue of Kaibara Ekken on his tomb at Kinryuji, a temple in the city of Fukuoka, in Kyushu.

Kaibara Ekken (16301714) was one of the leading Neo-Confucian thinkers of early modern Japan. Born in the beginning of the Tokugawa era (16001863), he had a significant intellectual influence during the period and is well respected in his birthplace of Fukuoka in northern Kyushu down to the present. Ekken was raised in a lower-ranking samurai family, was sent to study in Kyoto by the local provincial government (han), and subsequently was employed by the provincial lord (daimyo) as a government adviser. This ensured his career as a scholar and writer relatively free from financial concerns. His remarkable productivity was, no doubt, due to his moderate but secure income, as well as to the peaceful conditions established by the unification of the country under the Tokugawa shogunate. Moreover, he received invaluable assistance from his nephew, Kaibara Chiken, and his disciple Takeda Shunan. In addition, his wife was a talented woman who, it is conjectured, collaborated with him in some of his writings, particularly his diaries and travel accounts. Ekken was not unaware of these fortunate circumstances supporting his scholarly life. He frequently spoke of a feeling of gratitude for blessings received and the need to repay ones debt to the human and natural forces that sustain a persons life.

Ekkens sense of gratitude was closely linked to his empathic understanding of the suffering dimension of life, as he lost both his mother and his stepmother at an early age. Ekkens sympathies toward the more difficult aspects of life were, no doubt, also nurtured by growing up primarily amid townspeople outside the castle of the ruling daimyo rather than only among the samurai class. Furthermore, he lived for several of his early years in the countryside, where his proximity to the daily life of farmers inevitably stimulated his later interest in agriculture and botany. This breadth of life experience is reflected in the wide range of his concerns in his lecturing, research, and writing.

Next page

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK