BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cain, Michael L., and others. Ecology (Sinauer Associates, 2008).

Freeman, Jennifer. Ecology (Collins, 2007).

Fullick, Ann. Feeding Relationships (Heinemann, 2006).

Gibson, J.P., and Gibson, T.R. Plant Ecology (Chelsea House, 2006).

Krasny, Marianne, and others. Invasion Ecology, student ed. (NSTA Press, 2003).

Leuzzi, Linda. Life Connections: Pioneers in Ecology (Franklin Watts, 2000).

Quinlan, S.E. The Case of the Monkeys that Fell from the Trees: And Other Mysteries in Tropical Nature (Boyds Mills, 2003).

Scott, Michael. The Young Oxford Book of Ecology (Oxford Univ. Press, 1998).

Slobodkin, L.B. A Citizens Guide to Ecology (Oxford Univ. Press, 2003).

Ziegler, Christian, and Leigh, E.G. A Magic Web: The Forest of Barro Colorado Island (Oxford Univ. Press, 2002).

CHAPTER 1

THE NATURE OF ECOLOGY

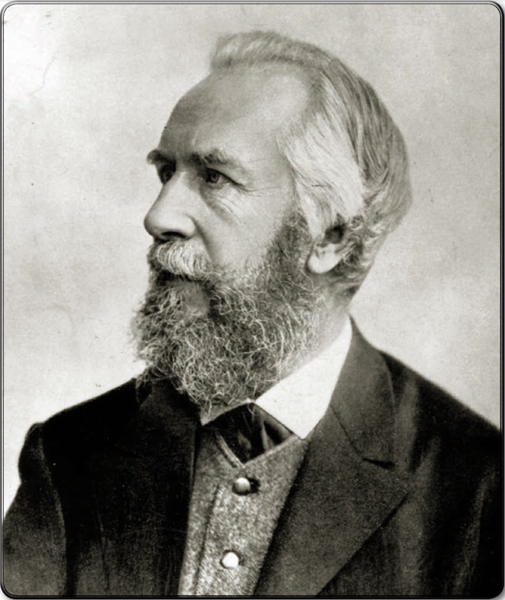

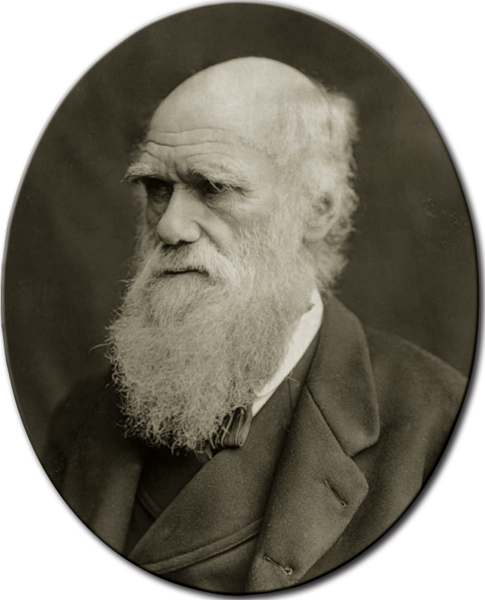

T he study of the ways in which organisms interact with their environment is called ecology. The word ecology was coined in 1869 by the German zoologist Ernst Haeckel, who derived it from the Greek oikos, which means household. Economics is derived from the same word. However, economics deals with human housekeeping, while ecology concerns the housekeeping of the natural world.

For many years most people did not consider ecology to be an important or even a real science. By the late 20th century, however, ecology had emerged as one of the most popular and important areas of biology. The effect of the environment on the organisms that inhabit it and vice versa is now acknowledged as a key element in a wide range of issues, including population growth, climate change, environmental pollution, species extinction, and human health and medicine.

Ernest Haeckel. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Many public health specialists are incorporating an ecological component in programs to control infectious diseases. For example, the rapid spread of West Nile virus (WNV) in the United States in the early 21st century resulted from the interaction of environmental factors with human and animal populations. Mosquitoes spread the virus by biting infected birds and then biting humans and other animals. One study in Florida noted that the number of WNV cases was especially high for years in which a dry spring season was followed by an especially wet summer. Further studies of environmental factors suggested that the limited water resources resulting from a dry spring may drive mosquitoes to congregate in isolated patches of dense vegetation where conditions remain humid. These humid patches also serve as nesting sites for an array of wild birds. In the close quarters of this temporary home, mosquitoes feed on and infect more birds than usual. When conditions change and the mosquitoes break out of their groupings and scatter, more people than usual will be bitten by these mosquitoes and become infected.

Such insights, gained from recognizing environmental factors promoting infection and transmission, are crucial for fighting WNV and many other diseases. If the ecology of the organisms is known, scientists can use an environmental approach to disrupt infection and the transmission of infectious diseases while treating and preventing the disease through medication and vaccination. This is but one example of the numerous ways in which scientists rely on an understanding of the complex interactions and interdependencies of living things and their environments.

Mosquitoes spread the West Nile virus by biting infected birds, then biting humans. Chris Johns/National Geographic Image Collection/Getty Images

EARLY STUDIES OF THE NATURAL WORLD

A gaggle of geese migrating south is a natural harbinger of impending winter. Shutterstock.com

Long before the science of ecology was established, people in many occupations were aware of natural events and interactions. Early humans knew that gulls hovering over the water marked the position of a school of fish. Before the use of calendars to mark time, people used natural cues to guide seasonal endeavors. For instance, corn (maize) was planted when oak leaves were a certain size, and the sight of geese flying south was a warning to prepare for winter.

Until about 1850, the scientific study of such phenomena was called natural history, and a person who studied this was called a naturalist. As natural history became subdivided into special fields, such as geology, zoology, and botany, naturalists began incorporating laboratory work with field studies. This multidisciplinary approach gradually led to the establishment of ecology as a distinct field of study.

MODERN-DAY ECOLOGY

The modern study of ecology encompasses many areas of science. In addition to a solid understanding of biology, ecologists must also have some knowledge of weather and climate patterns, rock and mineral types, soil, and water. Familiarity with mathematics and statistics is essential. Whereas the study of natural history was largely based on observation and record-keeping, today most ecological studies center around rigorous experimentation requiring testable hypotheses and statistical analysis.

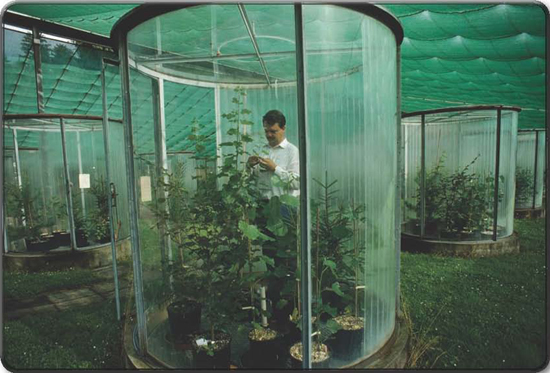

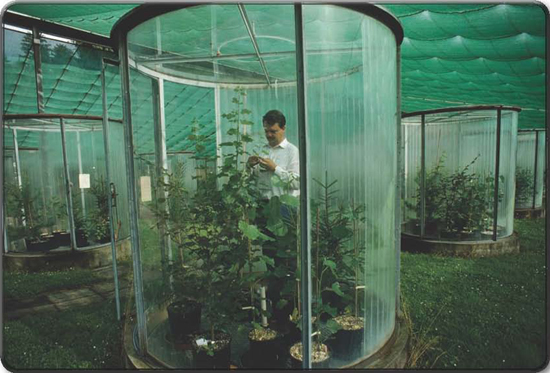

A Swiss scientist examines the effects of ozone on various plants via an open-top chamber in a laboratory. Sam Abell/ National Geographic Image Collection/Getty Images

Ecologists supplement their study of actual habitats with both computer models and laboratory experiments. In the laboratory, ecologists can construct environmental chambers in which they can control the temperature, humidity, light, and other variables. They can then change one or more of these variables in specific, controlled ways and see how this affects plants, animals, and other organisms they establish in the chambers.

INTERDEPENDENCE IN NATURE

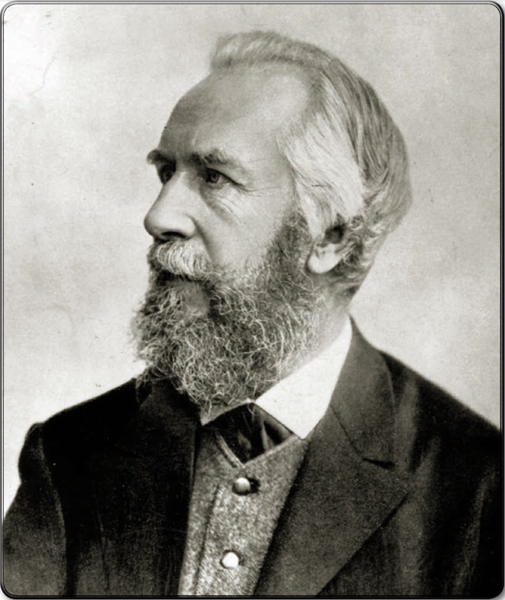

Ecology emphasizes the dependence of every form of life on other living things and on the natural resources in its environment, such as air, soil, and water. The English biologist Charles Darwin noted this interdependence when he wrote:

It is interesting to contemplate a tangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and so dependent upon each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us.