Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK WAS NOT REALLY MY IDEA, BUT EVOLVED OUT OF AN ELAB-orate encounter with a sentient mesh. I have always been grateful for the plant ecosystem from whence we have manifested in order to move plant genes around and explore the space of all possible experiences, but I now realize that I am that mesh, and for that unmistakable teaching I give thanks to the late Norma Panduro. From the very beginnings of the project all doubts were brought low before my admiration for the psychonautic researchers I was fortunate enough to meet and read. Thanks MAPS! Gracias Erowid! Sasha and Ann Shulgin welcomed me to their kitchen table many years ago as well as visited my seminar at UC Berkeley, encouraging me beyond all words with their joyful spirit and immense intelligence. I knew that following these Bodhisatvas in their research could not be the wrong path. Dennis McKenna exemplifies the fierce inquiry of open minded science and courageous investigation of selfsomeday there will be a Nobel for Psychonautics, may it be named for the Shulgins and given to the McKennas.

My family, with whom I am ever more intensely and joyfully enmeshed, taught and loved me so well that I survived and flourished through this extraordinary healing ordeal. Violet, Jackson, and Amy: Groove Hug! Thanks to my dad, who taught me to follow the data, my late mother, who counseled me even in the rain forest, my sister, the Indomitable, and my late brother, who set me on this path twenty-three years ago. I'm getting there, brother!

Kathleen Pike Jones, Paul Bowersox, and Jacquie Ettinger were of immense help in putting this logos flow between covers.

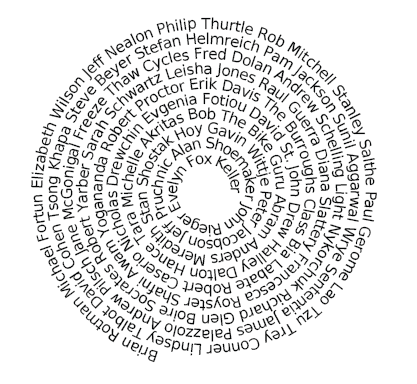

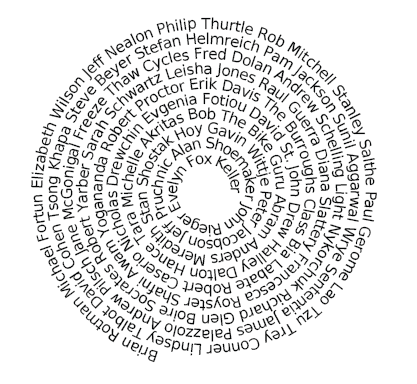

Cue the Spiral of Friends & Allies:

THE FLOWERS OF PERCEPTION

Trip Reports, Stigmergy, and the Nth Person Plural

This plant, although itself hardly mobile, casts a spell over what is wakened, for instance, by tea, tobacco, opium, often just by the mere scent of flowers.

Ernst Jnger, The Plant as Autonomous Power

Even though, as fungi, mushrooms do not blossom, the Aztecs referred to them as flowers, and the Indians who still use them in religious rituals have endearing terms for them, such as little flowers.

Richard Evans Schultes, Albert Hofmann, and Christian Rtsch, Plants of the Gods

IF WE ARE TO RESPOND ETHICALLY (NOT TO MENTION SCIENTIFICALLY) to the presence of psychedelic technologies in our cultures, then it would seem a good idea to evaluate what they are. This ontological questionWhat are psychedelics?would seem to come before any reasoned or practical response to the systematic alteration of consciousness in interaction with plant compounds or their simulacra. We must at least pose, if not answer, questions about the kinds of practices they are if we are to respond with care to these ancient but nonetheless transhuman technologies.

As compounds, we could quite usefully group psychedelics under the categories phenethylamines and tryptamines. Alexander and Ann Shulgin used these categories as a way of organizing both their chemical research and their (fictional) writings about said investigations., endlessly toy with. Prospecting for novel psychedelics and the pathways for their synthesis becomes an endlessly differentiating glassbead game, the leading edge of a molecular evolution whose bounds are uncertain but ongoing.

The pathways to synthesize these compounds are remarkable works of creativity in their own right, and carefully following the cascades of reactions that lead one from aluminum foil to MDMA involves a cognitive and perceptual gymnastics no less intensive than listening to a symphony. Consider, for example, the group tinker of the Brazil Caper, wherein Shura (Alexander Shulgin's fictional alter ego) presided over the preparation of a batch of MDMA for a barely equipped clinic in Rio:

There was an old rotary evaporator which wobbled alarmingly; Shura patched it with duct tape. There was a superb Bchner Funnel among the treasures, but no sign of filter paper of the right size, so our boys cut out a substitute from a piece of paper towel.Hooking up, pulling down, fitting on, screwing in, both of them were delighted with the challenge one moment, despairing the next, hoping all over again, and mildly hysterical most of the time. (Shulgin and Shulgin 1997, 92)

Yet however engaging the synthetic pathway of any given compound ishere we are watching MDMA becomethe scientific literature of psychedelics is clear on this point: the compounds are interesting precisely and perhaps only because of their effects on a human consciousness. AliceAnn's fictional alter egoshares in Shura's dance even as she narrates it: Hooking up, pulling down, fitting on, screwing in, even the fabrication of MDMA seems to induce contagious and connective rhythms.

Hence while remarkable, the tinker toy, molecular definition of psychedelics is insufficient for any real apprehension of what they are, or why MDMA does or does not belong to the category psychedelic. This universe of play is quite helpful in the replication and differentiation of psychedelic compounds, yet even participating in this play tells us (almost) nothing about why anyone would replicate psychedelic experience in the first place. It teaches us the joys of molecular evolution and the sensus communis often at play in the psychedelic community, but it tells us little about anything specific to the molecular evolution of psychedelics, whether that evolution takes place in a plant ecoystem or a lab. Creativity, theologian and perennial philosopher Matthew Fox tells us, is Divine. But are psychedelics themselves involved in the divine in any fashion distinct from, say, the same sort of tinkering with a computer, a bicycle, a house, a greenhouse? This is the ontological question raised by entheogen.

For evidence concerning the nature of psychedelics, then, we must turn to the only kind of data we have: first person testimonies about experiences with these materials. In this context, trip reports are the readout produced by a human consciousness and a particular compound. This readout is itself usable in multiple ways, and interpretable only in the context of the possible differentiations of set and setting embedding any particular compound or plant. Thus when the Shulgins wrote up the diverse tryptamines and phenethylamines, it was not only the itinerary from one compound to anotherthe steps of synthesisthat demanded articulation; they also needed to provide character development and community analysis if they were to situate the effects of the compounds on any given psychonaut such that they could be usefully repeated. It is in this latter sense that the voices of Tihkal and Pihkal are as vital to psychedelic science as their famous chemical recipes: the multiply voiced, famously and obviously pseudonymic characters of Shura and Alice provide fluctuating but actual rhetorical frameworks for the investigation of psychedelic experience, softwares for further research.

And yet how are we to read this data? Testimony concerning psychedelic experience faces several rhetorical challenges. In a later chapter we will watch as Albert Hofmann struggles even to speak, let alone speak well and persuasively about his discovery, LSD-25. And language itself appears to be insufficient to the synesthesias and beyond of psychedelic research. Few elements in a trip report are more predictable than a version of words fail me. To make matters worse, psychonauts find themselves rhetorically challenged on yet another front: trip reports are written by users of psychedelic drugs. Why would we listen to such babble?

And yet properly contextualized, all of these features of psychedelic testimony can be viewed as aspects of ecodelic experience. The continual disavowal of language

Next page