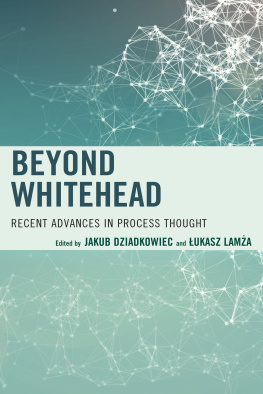

Without Criteria

Technologies of Lived Abstraction

Brian Massumi and Erin Manning, editors

Relationscapes: Movement, Art, Philosophy, Erin Manning, 2009

Without Criteria: Kant, Whitehead, Deleuze, and Aesthetics, Steven Shaviro, 2009

Without Criteria: Kant, Whitehead, Deleuze, and Aesthetics

Steven Shaviro

The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England

2009 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information about special quantity discounts, please email

This book was set in Garamond and Rotis semi-sans by Binghamton Valley Composition in Quark.

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shaviro, Steven.

Without criteria : Kant, Whitehead, Deleuze, and aesthetics / Steven Shaviro.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-262-19576-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Whitehead, Alfred North, 1861-1947. 2. Aesthetics. 3. Deleuze, Gilles, 1925-1995. 4. Heidegger,

Martin, 1889-1976. 5. Kant, Immanuel, 1724-1804. I. Title.

B1674.W354S442009

192dc22

2008041142

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Series Foreword

Preface: A Philosophical Fantasy

1 Without Criteria

2 Actual Entities and Eternal Objects

3 Pulses of Emotion

4 Interstitial Life

5 God, or The Body without Organs

6 Consequences

References

Index

Technologies of Lived Abstraction

Erin Manning and Brian Massumi, editors

"What moves as a body, returns as the movement of thought".

Of subjectivity (in its nascent state)

Of the social (in its mutant state)

Of the environment (at the point it can be reinvented)

"A process set up anywhere reverberates everywhere".

The Technologies of Lived Abstraction book series is dedicated to works of transdisciplinary reach inquiring critically but especially creatively into processes of subjective, social, and ethical-political emergence abroad in the world today. Thought and body, abstract and concrete, local and global, individual and collective: the works presented are not content to rest with the habitual divisions. They explore how these facets come formatively, reverberatively together, if only to form the movement by which they come again to differ.

Possible paradigms are many: autonomization, relation; emergence, complexity, process; individuation, (auto)poiesis; direct perception, embodied perception, perception-as-action; speculative pragmatism, speculative realism, radical empiricism; mediation, virtualization; ecology of practices, media ecology; technicity; micropolitics, biopolitics, ontopower. Yet there will be a common aim: to catch new thought and action dawning, at a creative crossing. The Technologies of Lived Abstraction series orients to the creativity at this crossing, in virtue of which life everywhere can be considered germinally aesthetic, and the aesthetic anywhere already political.

"Concepts must be experienced. They are lived."

Preface: A Philosophical Fantasy

This book originated out of a philosophical fantasy. I imagine a world in which Whitehead takes the place of Heidegger. Think of how important Heidegger has been for thinking and critical reflection over the past sixty years. What if Whitehead, instead of Heidegger, had set the agenda for postmodern thought? What would philosophy be like today? What different questions might we be asking? What different perspectives might we be viewing the world from?

The parallels between Heidegger and Whitehead are striking. Being and Time was published in 1927, Process and Reality in 1929. Two enormous philosophy books, almost exact contemporaries. Both books respond magisterially to the situation (Id rather not say the crisis) of modernity, the immensity of scientific and technological change, the dissolution of old certainties, the increasingly fast pace of life, the massive reorganizations that followed the horrors of World War I. Both books take for granted the inexistence of foundations, not even fixating on them as missing, but simply going on without concern over their absence. Both books are antiessentialist and antipositivist, both of them are actively engaged in working out new ways to think, new ways to do philosophy, new ways to exercise the faculty of wonder.

And yet how different these two books are: in concepts, in method, in affect, and in spirit. Id like to go through a series of philosophical questions and make a series of (admittedly tendentious) comparisons, in order to spell out these differences as clearly as possible.

1 The question of beginnings Where does one start in philosophy? Heidegger asks the question of Being: Why is there something, rather than nothing? But Whitehead is splendidly indifferent to this question. He asks, instead: How is it that there is always something new? Whitehead doesnt see any point in returning to our ultimate beginnings. He is interested in creationrather than rectification, Becoming rather than Being, the New rather than the immemorially old. I would suggest that, in a world where everything from music to DNA is continually being sampled and recombined, and where the shelf life of an idea, no less than of a fashion in clothing, can be measured in months if not weeks, Whiteheads question is the truly urgent one. Heidegger flees the challenges of the present in horror. Whitehead urges us to work with these challenges, to negotiate them. How, he asks, can our cultures incessant repetition and recycling nonetheless issue forth in something genuinely new and different?

2 The question of the history of philosophy Heidegger interrogates the history of philosophy, trying to locate the point where it went wrong, where it closed down the possibilities it should have opened up. Whitehead, to the contrary, is not interested in such an interrogation. It is really not sufficient, he writes, to direct attention to the best that has been said and done in the ancient world. The result is static, repressive, and promotes a decadent habit of mind. Instead of trying to pin down the history of philosophy, Whitehead twists this history in wonderfully ungainly ways. He mines it for unexpected creative sparks, excerpting those moments where, for instance, Plato affirms Becoming against the static world of Ideas, or Descartes refutes mind-body dualism.

3 The question of metaphysics Heidegger seeks a way out of metaphysics. He endeavors to clear a space where he can evade its grasp. But Whitehead doesnt yearn for a return before, or for a leap beyond, metaphysics. Much more subversively, I think, he simply does metaphysics in his own way, inventing his own categories and working through his own problems. He thereby makes metaphysics speak what it has usually denied and rejected: the body, emotions, inconstancy and change, the radical contingency of all perspectives and all formulations.

4 The question of language Heidegger exhorts us to hearken patiently to the Voice of Being. He is always genuflecting before the enigmas of Language, the ways that it calls to us and commands us. Whitehead takes a much more open, pluralist view of the ways that language works. He knows that it contains mysteries, that it is far more than a mere tool or instrument. But he also warns us against exaggerating its importance. He always points up the incapacities of languagewhich means also the inadequacy of reducing philosophy to the interrogation and analysis of language.

Next page