LIGHT TRACES

STUDIES IN CONTINENTAL THOUGHT

John Sallis, editor

Consulting Editors Robert Bernasconi

Rudolph Bernet

John D. Caputo

David Carr

Edward S. Casey

Hubert Dreyfus

Don Ihde

David Farrell Krell

Lenore Langsdorf

Alphonso Lingis

William L. McBride

J. N. Mohanty

Mary Rawlinson

Tom Rockmore

Calvin O. Schrag

Reiner Schrmann

Charles E. Scott

Thomas Sheehan

Robert Sokolowski

Bruce W. Wilshire

David Wood

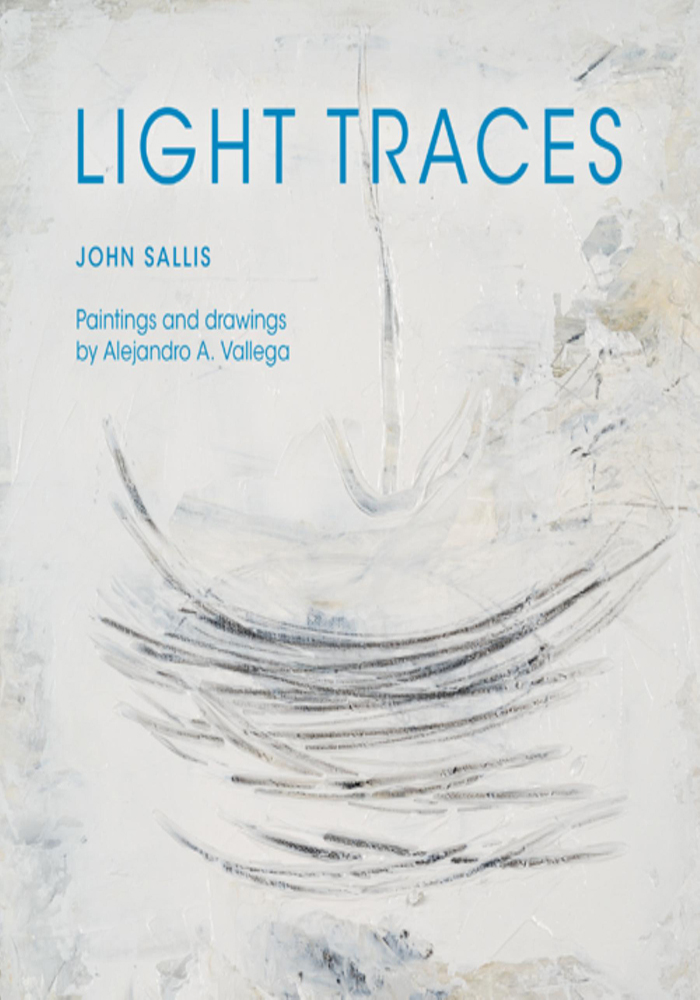

LIGHT TRACES

JOHN SALLIS

Paintings and drawings

by Alejandro A. Vallega

Indiana University Press Bloomington & Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East Tenth Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone 800-842-6796

Fax 812-855-7931

2014 by John Sallis (text) and

Alejandro A. Vallega (images)

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in China

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sallis, John, [date]

Light traces / John Sallis; paintings and drawings by Alejandro A. Vallega.

pages cm. (Studies in Continental thought)

ISBN 978-0-253-01282-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-253-01303-3 (ebook) 1. Place (Philosophy) 2. Light. I. Vallega, Alejandro A., illustrator. II. Title.

B105.P53S245 2014

113 dc23

2013034396

1 2 3 4 5 19 18 17 16 15 14

To live is to behold the

light of the sun.

Homer

Contents

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sarah Grew for her generosity in providing the photographic images and to Nancy Fedrow for her assistance in preparing the manuscript. We want especially to thank our friend and editor Dee Mortensen for the encouragement and advice she has so generously offered us during our collaboration on this project. Thanks also to Sean Driscoll for editorial assistance.

J. S.

A.V.

Anagoge

The return of light in spring brings joy and hope to living things. For in one way or another light governs virtually everything of concern to them. It makes visible the things around them; it lets the presence of things and of natural elements be sensed in the most disclosive manner; and thereby it clears the space within which things can be most sensibly encountered and elements such as earth and sky can be revealed in their gigantic expanse. The coming and going of natural light also gives the measure of time, coming to bestow the day, retreating to give way to night. Light also measures out the seasons, not only by its intensity as the sun appears higher or lower in the sky, but also by variations that are not readily expressible in traditional categories: as with the crystal-clear sunlight of certain winter days when the scattered clouds appear in sharpest contour against a sky so blue that it exceeds all that can be said in the word blue.

With the new light that marks the arrival of spring and that brings with it the promise of warmth, the threats of winter recede. Fresh growth appears, first as little more than a fine green haze and then in delicate forms that attest to the fecundity of nature, still held in store but portended by these light traces. Now abundant vitality is displayed by all animate creatures. We humans, too, welcome the arrival of spring, not only in our ordinary actions but also in exceptional events such as rites and festivals. For the ancient Athenians festivals were so decisive in marking not only the arrival of seasons but all the months of their lunar calendar that each month literally bore the name of the chief festival celebrated within its time-span.

Yet as it returns, light remains curiously inconspicuous, even more so than the natural finery that its return will eventually release from the things with which nature surrounds us. For quite some time after the winter solstice, we are scarcely aware of the increasing daylight; and it may happen almost suddenly, several weeks later, that we notice the lengthening of the day. It is as if the luminous generosity were effected by stealth.

Light is also inconspicuous in another way, in a way that is itself inconspicuous, hardly noticed at all.

Picture a scene in the forest where sunlight is shining through the branches onto the ground below. There will be areas that are brightly illuminated, others that are shaded, and, as a result, a configuration of light and shadow on the forest floor. There will also be visible illumination on some of the branches above. Yet in the space between the lowest branches and the forest floor, no illumination will be visible. Though light must traverse this space in order to illuminate the ground below, it remains entirely invisible. Only if the space contains particles of dust or a bit of mist or fog that is, things to be illuminated does the ray of light become visible. Even on the forest floor what we actually see is not the light itself but the ground illuminated by the light. The light itself, which bestows on things their visibility, remains to this extent invisible. It goes unseen, and yet in connection with what is seen, it displays a trace that is indicative of its effect, of its being operative there at the site of the visible. Unlike an image, in which an aspect of some visible thing is presented, a trace does not present anything; it is, rather, that by which something otherwise concealed, something irreducible to a thing that is present, signals that it is nonetheless operative there in the very thick of visible things.

Of light there are, then, only traces. To turn to the light is to attend to light traces.

In most instances it is also to turn ones gaze upward toward the primary source of light. Accordingly, the turn to the light is linked to the preeminence of the sky, to our affinity with the heights, and to the prospect of ascendancy. In all these inclinations the directive is given by light traces. It is light that traces the upward way, that evokes the aspiration for flight, which, in various metaphorical registers, moves us at the most elemental level. Nothing human goes untouched by this aspiration; nothing is immune to the measure of the upward way, neither to its promise nor to its peril.

Traces are necessarily light. They are, like light itself, free of the weight of things materially present. Even when they are drawn or inscribed and thus transposed into a minimally present double, they retain much of their lightness. The triangle that is drawn in order to facilitate intuition must in effect erase itself in the course of the demonstration it serves. For it is not really an image or picture through which the triangle itself would be presented. Formed by lines that are without width and hence, strictly considered, are invisible, a triangle is itself invisible; and a drawing can be nothing more than a trace serving to bring the figure to light.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.