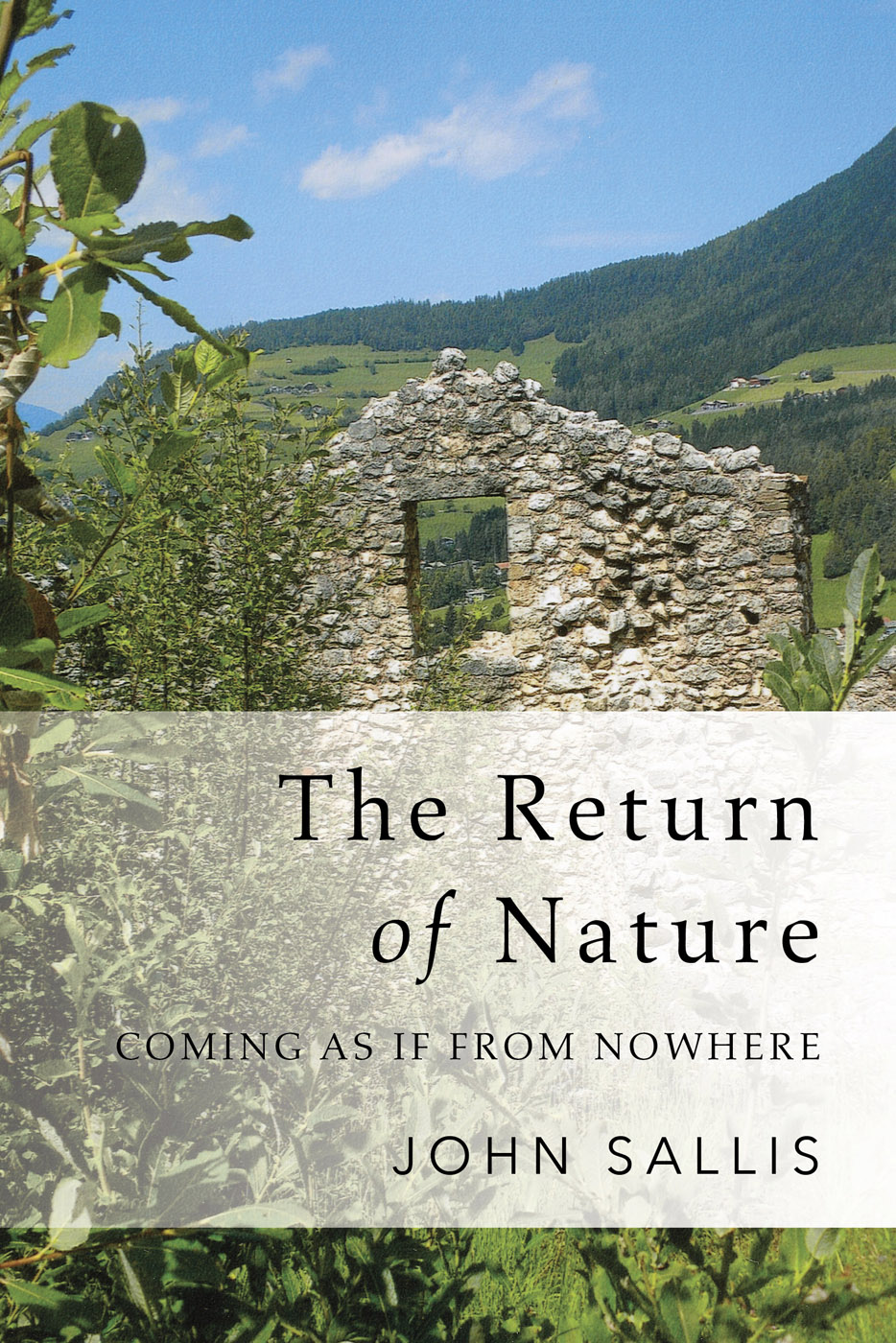

THE RETURN OF NATURE

STUDIES IN CONTINENTAL THOUGHT

John Sallis, editor

CONSULTING EDITORS

Robert Bernasconi | James Risser |

John D. Caputo | Dennis J. Schmidt |

David Carr | Calvin O. Schrag |

Edward S. Casey | Charles E. Scott |

David Farrell Krell | Daniela Vallega-Neu |

Lenore Langsdorf | David Wood |

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Bloomington & Indianapolis

The Return of Nature

ON THE BEYOND OF SENSE

JOHN SALLIS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2016 by John Sallis

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sallis, John, 1938- author.

Title: The return of nature : coming as if from nowhere / John Sallis.

Description: Bloomington : Indiana University Press, 2016. | Series: Studies in Continental thought | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016010956 (print) | LCCN 2016030782 (ebook) | ISBN 9780253022899 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780253023131 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780253023377 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Philosophy of nature.

Classification: LCC BD581 .S243 2016 (print) | LCC BD581 (ebook) | DDC 113dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016010956

1 2 3 4 5 21 20 19 18 17 16

There are moments in our lives when we extend a kind of love and tender respect to nature in plants, minerals, animals, and landscapes, as well as to human nature in children, in the customs of country folk and the primitive world, not because it pleases our senses, not even because it satisfies our understanding or taste , but merely because it is nature.

Friedrich Schiller, ber nave und sentimentalische Dichtung

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For permission to draw on previously published material, I am grateful to the editors/publishers of the following journals: Internationales Jahrbuch fr Hermeneutik, Southern Journal of Philosophy, and Journal of Speculative Philosophy. Thanks also to the editor and publisher of Phenomenological Perspectives on Plurality.

All translations are my own.

I am grateful to Nancy Fedrow, Ryan Brown, and Stephen Mendelsohn for their fine assistance during production of this book. The support that my editor and friend Dee Mortensen has provided for the present project has been indispensable, and I am especially grateful to her.

Boston

May 2016

THE RETURN OF NATURE

PROLOGUE

The way along which nature returns from its destitution may lead it to itself, to nature itself, to nature as it itself is, perhaps even as it is in its fullness, as when from the dead of winter nature is reborn in the abundance of its growth. Or it may return in a guise other than that proper to it; it may return in such disguise that it itself, it as it is in itself, is barely to be recognized, as when it is disfigured by forces alien to it, forces that, even if they seem to stem from nature, are contrary to those that belong to it by nature. The way on which nature returns, the cycle of the seasons, for instance, is finely articulated: it is not just a course on which nature circles endlessly but also one that is measured and marked by the phases of natures withdrawal and return. Nature returns also along a course that is entwined with that of the seasons, the course marked by the nocturnal withdrawal of light and its return with the coming of day by which visibility is restored to all things. On this course each segment has its distinctive character: the colors of dawn, the burst of light at sunrise, the freshness of the morning, the intensity of high noon, the fading light and long shadows of late afternoonand on toward dusk, the coolness and dampness of night, and on clear nights the appearance of stars, and always the withdrawal of terrestrial things into nocturnal obscurity. On other occasions, for instance, when the weather is unsettled, when thick clouds block the direct sunlight and a cold wind sweeps across the landscape, the course of day and night is articulated in quite a different manner; but regardless of the conditions, this course is measured and marked by the phases in which nature withdraws and returns.

There are occasions, even entire eras, when human intervention drives nature itself to recede behind the fabrications constructed from it. Eventual dereliction may open the space for nature itself to return. Or persistent exploitation may block its return as itself, may allow it to return only as a ghost of what it otherwise would be. Or a theoretical stance oriented to all that would be entirely and invariably itself may posit nature itself beyond nature as it is displayed before our senses; as such, this nature beyond nature will be set beyond all possibility of return and will be regarded as merely imaged by the nature that lies before us, which is thus reduced to a mere remote semblance of nature as it itself, in its utter selfsameness, is.

The return of nature may evoke a return to nature. With the coming of spring, as we catch sight of the first buds, the tiny leaves, and the other traces of all that will soon arrive, we are enticed by the visible promise of abundance and perhaps even impelled to venture into the surrounding nature. Likewise, it is with the return of light in the morning that we are prompted to set out as the day requires, leaving the shelter that secured us in the night, advancing into the midst of the elements that both embrace us and threaten us. We are perhaps most compellingly drawn to nature when the shining of the things of nature exceeds both our grasp and our words. The beauty of nature may, then, prove to outstrip even that of which art is capable. Indeed, one might imagine a paradigmatic scene in which a person with a genuine sense of beauty would take leave of the museum in order to venture into the open expanse where he might linger before the beauty of nature.

Yet, in order for the splendor of beautiful nature to exercise its attraction, it must become manifest. Indeed, the attraction and the retraction of nature can be displayed before us only if the things of nature become manifest as they are gathered into natures return and withdrawal. They must show themselves in such a manner that they can be apprehended by sense along with whatever comes to the aid of sense, whatever comes to complete what sense alone can never quite achieve. One of the names that have been given to that which comes to supplement sense is imagination. Only through the coming of imagination is it possible to apprehend natural things (animals, flowers, grasses, stones) as well as things fabricated from nature (architectural edifices, utensils of all sorts, instruments for various purposes). Only through the coming of imagination can such things be displayed before us, either as they cohere within the return and withdrawal of nature or as (in the case of fabricated things) they are set at the limit of nature.

Next page