TWELVE EXAMPLES OF ILLUSION

JAN WESTERHOFF

TWELVE EXAMPLES OF ILLUSION

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further

Oxford Universitys objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright 2010 Oxford University Press, Inc.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Westerhoff, Jan.

Twelve examples of illusion / Jan Westerhoff.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 9780-19-538735-3

1. Illusion (Philosophy). 2. Buddhist philosophy. I. Title.

B105.I44W47 2010

294.342dc22

2009033100

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in China

on acid-free paper

Once upon a time there was a king in India. An astrologer told him: Whoever shall drink the rain which falls seven days from now shall go mad So the king covered his well, that none of the water may enter it. All of his subjects, however, drank the water, and went mad, while the king alone remained sane. Now the king could no longer understand what his subjects thought and did, nor could his subjects understand what the king thought and did. All of them shouted The king is mad, the king is mad Thus, having no choice, the king drank the water too.

TWELVE EXAMPLES OF ILLUSION

INTRODUCTION

A CERTAIN Tibetan encyclopedia called A Feast for the Intelligent Mind lists twelve examples of illusion as follows:

I. Magical illusions | VII. A city of Gandharvas |

II. The moon in the water | VIII. Optical illusions |

III. Visual distortions | IX. Rainbows |

IV. Mirages | X. Lightning |

V. Dreams | XI. Water bubbles |

VI. Echoes | XII. A reflection in a mirror |

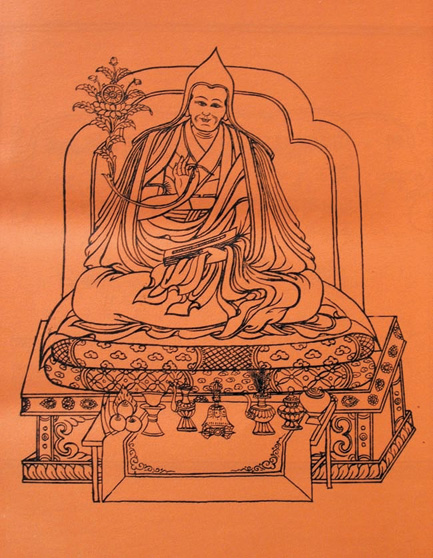

The author of this encyclopedia, the eighteenth-century Tibetan scholar Konchog Jigme Wangpo, saw the world as a collection of lists. A well-read and prolific writer like his previous incarnation, he set himself the task of enumerating all the objects that come in pairs, all that come in triples, in sets of four, five, six, or more.

Among other things his encyclopedia tells us about the two truths (the absolute and relative truth), the three sweet substances (crystalline sugar, sugar-cane juice, and honey), three pursuits of the learned (explanation, debate, and composition), the four languages of India (Sanskrit, Prakrit, Apabhrarnsa, and Pisacihands, the desire to copulate), the five gifts of the cow (urine, dung, milk, butter, curd), the six tastes of medicine (sweet, sour, bitter, astringent, hot, and salty), the seven parts of an elephant (first leg, second leg, third leg, fourth leg, tail, testicles, trunk), seven constituents of the body (blood, flesh, fat, bone, marrow, semen, and water), the eight aspects of water (cool, light, tasty, smooth, clear, without smell, pleasing to the throat, not harmful to the stomach), and the eight grammatical cases (nominative, accusative, instrumental, dative, ablative, genitive, locative, and vocative).

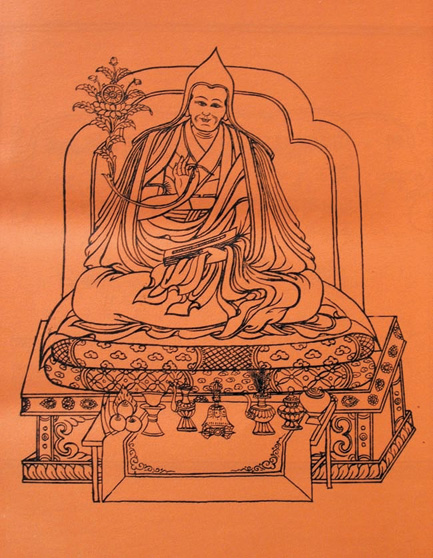

Knchog Jigme Wangpo

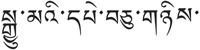

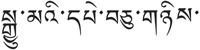

A particularly intriguing piece among the many treasures of this wonder-house of a Tibetan encyclopedia is the list of the twelve examples of illusion. Konchog Jigme Wangpo drew these twelve examples from texts usually classified by Buddhist scholars under the heading Perfection of Wisdom or Prajndpdramitd in Sanskrit. The first texts of this sort were probably written in southern India during the first century BCE; their composition continued for the following millenium. They range in length from enormous compendia like the Perfection of Wisdom in 100,000 Lines (which amounts to more than a million words of English) to versions that fill a normal-sized volume, such as the Perfection of Wisdom in 8,000 Lines, or just a single page, like the famous Heart Sutra, and finally to the ultimately abbreviated recensions in texts like the Perfection of Wisdom in One Letter, which consists just of the letter

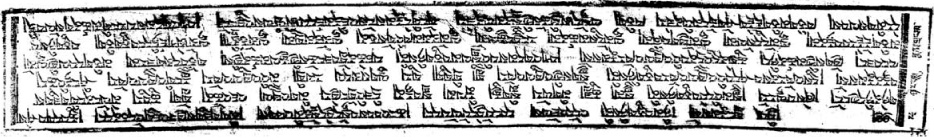

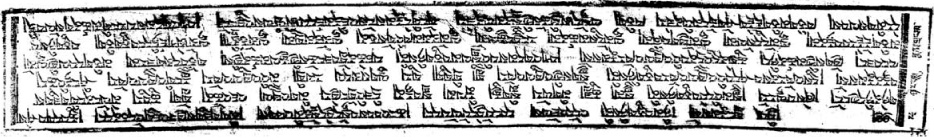

Page showing the list of the twelve examples of illusion (lines 23)

The Perfection of Wisdom texts are notoriously difficult to understand and tend to make the most startling claims. Here is an extract from the Heart Sutra.

Matter is emptiness, and emptiness itself is matter. Matter is not distinct from emptiness, and emptiness is not distinct from matter.... All things are marked by emptiness, not arisen, not ceased, not pure, not defiled, not diminishing, not increasing. In emptiness... there is no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind, no shape, no sound, no smell, no taste, nothing to be touched and nothing to be thought of.... There is no knowledge, no ignorance, no ending of ignorance, no ending of old age and death, there is no suffering, no cessation of suffering, no path leading to this cessation, there is no wisdom, there is no attainment, and no non-attainment either.

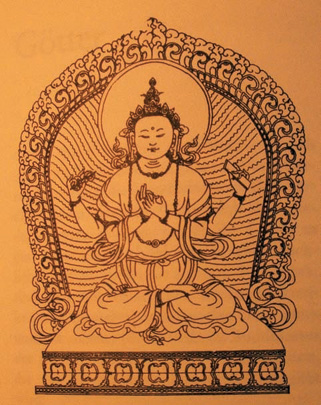

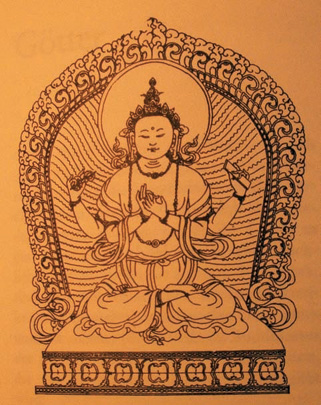

Despite their great difficulty and often cryptic style, these texts became so popular that the Perfection of Wisdom was soon personified. Since Prajnaparamita is a feminine Sanskrit noun, she is depicted in female form. The Tibetan tradition represents her with four arms; the two outer arms hold a book (as befits the personification of wisdom) and a rosary, or sometimes a scepterlike object called a vajra, derived from the thunderbolt of the Vedic god Indra and generally regarded as a sign of permanence and indestructibility. Her other two hands are sometimes folded in her lap in the gesture of meditation, holding a vase filled with the nectar of immortality. In the depiction represented here Prajnaparamita holds her hands in front of her chest in the gesture of teaching.

Personification of the Perfection of Wisdom

Next page