Daoism, Meditation,

AND THE

Wonders of Serenity

SUNY SERIES IN C HINESE P HILOSOPHY AND C ULTURE

Roger T. Ames, editor

Daoism, Meditation,

AND THE

Wonders of Serenity

From the Latter Han Dynasty (25220) to the Tang Dynasty (618907)

STEPHEN ESKILDSEN

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS

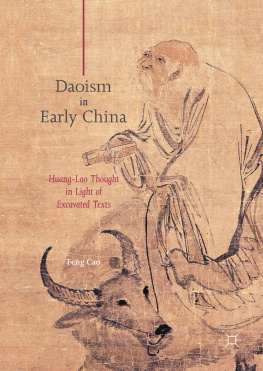

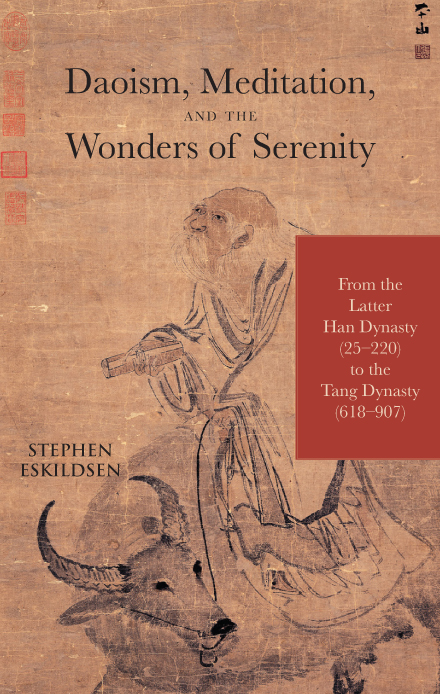

Cover illustration: Laozi Riding an Ox , hanging scroll, light color on paper, 101.5 55.3 cm.

National Palace Museum, Taiwan. Laozi is carrying a copy of the Dao De Jing .

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2015 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Dana Foote

Marketing, Michael Campochiaro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Eskildsen, Stephen

Daoism, meditation, and the wonders of serenity : from the latter Han dynasty (25220) to the Tang dynasty (618907) / Stephen Eskildsen.

pages cm.(SUNY series in Chinese philosophy and culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-5823-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)ISBN 978-1-4384-5824-3 (e-book) 1. MeditationTaoism. 2. TaoismChinaHistoryTo 1500. I. Title.

BL1923.E845 2015

299.5'1443509dc23

2014045580

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

C ONTENTS

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have never taken up the practice of meditation because I seriously lack patience and bodily flexibility. Attempting certain meditation postures such as the full lotus position would probably kill me. The restricted dietary regimens that frequently accompany meditation practice are also problematic, as I tend to require more nutrition than the average person. However, the experiences of people who meditateespecially if they are Daoistssomehow fascinate me.

This book developed over the course of the past ten years as my constant curiosity toward Daoism, meditation, and mystical experience drew my attention toward specific texts that vividly attest to the variety and magnitude of sensory and physical phenomena that may be brought about just by making the mind clear and calm. Actually, such texts range in date from the Latter Han right down to the modern period, and I had originally envisioned a volume of much broader chronological scope than this one. However, I eventually came to realize that the Han-through-Tang material easily yielded enough interesting data to fill a monograph, and that a proper, careful analysis of the Neidan (internal alchemy) materials of the Song period onward was an endeavor that needed to be deferred to the future.

Most of the material in this book has not been previously published. Exceptions to this are found in parts of chapter 3 and chapter 4. Some of the discussion on The Manifest Dao has appeared in my article Some Troubles and Perils of Taoist Meditation ( Monumenta Serica , no. 56 [2008]): 259291). Some of the discussion on Contemplating the Baby and The True Record has appeared in my recent article Red Snakes and Angry Queen Mothers: Hallucinations and Epiphanies in Medieval Daoist Meditation (in Hindu, Buddhist and Daoist Meditation: Cultural Histories , ed. Halvor Eifring [Oslo: Hermes Publishing, 2014], 149184). Some of the discussion on The Original Arising appeared in my article Mystical Ascent and Out-of-Body Experience in Medieval Daoism ( Journal of Chinese Religions 35 [2007]: 3662).

The people I need to thank on this occasion are many. My gratitude goes out to all of my teachers of past years, especially Daniel Overmyer and Joseph McDermott. I am grateful to the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga for providing me with a happy work environment for many years, and for providing me with a Faculty Research Grant to do fieldwork in China during the summer of 2010. I thank all of my friends and colleagues in Chattanooga for their kindness over the years. I thank Nancy Ellegate and her fine staff at the State University of New York Press, along with the two anonymous readers who took the time to read the manuscript carefully and provide helpful, insightful feedback.

Perhaps the main reason for why I was finally able to complete this book this year was that I had the outrageous good fortune of receiving a one-year Visiting Research Fellowship from the Kte Hamburger Kolleg, Dynamics in the History of Religions between Asia and Europe situated at the Ruhr-University Bochum (Germany). My stay in Bochum has been extremely intellectually stimulating, and has allowed me the time and resources to complete my project. I would like to particularly thank Volkhard Krech, Licia DiGiacinto, and Lucia an der Brgge for their generosity.

But my most constant companion and supporter over the past decade has been my wife, Eiko Namiki. I thank her for her love and encouragement, and look forward to her future scholarly monographs. I also thank Hana-chan and Kobuton (the ascended) for all of the furry, cuddly comfort that they have provided. Finally, I send my love and gratitude to my parents Edward and Marion Eskildsen, my brothers Tom and Walter, and my Aunt Lucileall of whom have been a blessing to me for my entire life.

ONE

I NTRODUCTION

OPENING COMMENTS

D aoism has always emphasized mental serenity and maintained that good effects will come about from it. To be serene means that the mind is clear ( qing ), or free of any thoughts that confuse it; it also means that the mind is calm ( jing ), without any emotions that agitate it. Daoism maintains that you should foster serenity at all times and in all activities. Activity itself is best limited to only what is most natural ( ziran ) and necessarynonaction ( wuwei ) is thus frequently enjoined.

For Daoists, meditation has been a primary means of fostering serenity and bringing it to greater depths. The greatest depths of serenity are entranced states of consciousness wherein mystical insights or experiences are said to come about,are said to be activated and mobilized in most salubrious and wondrous ways. However, for such wondrous occurrences to come about in full abundance, it is frequently maintainedas we shall seethat your method of meditation ought to be simple and passive, apparently so as not to hinder the wonders that can only arise naturally. Less is more in all things, including meditation.

However, such elaborate, proactive meditation techniques are not described or endorsed in ancient Warring States (Zhanguo ; 403221 BCE) period Daoist texts such as the Laozi (The Old Master, aka Daode jing [Classic of the Way and the Virtue]), the Zhuangzi (Master Zhuang) or the Neiye (Inner Training). These texts endorse the habitual fostering of serenity throughout all circumstances and activities; if and when they do specifically speak of meditation, the method seems to involve little more than just calming and emptying out the mind.

As we shall see in this book, despite the profusion of proactive meditation techniques in Daoism during the first millennium of the Common Era, there also continued to exist and develop more passive approaches to meditation that calmly observed the processes that unfold spontaneously within the mind and body. Theorists and practitioners of such methods claimed that through deep serenity one could variously attain profound insights, experience numerous sorts of visions, feel surges of salubrious qi in the body, overcome thirst and hunger, be cured of all ailments and decrepitude, ascend the heavens, and gain eternal life. While they did not necessarily reject or disdain the proactive methods, they often viewed them as conferring lesser blessings, or as being rudimentary methods that should or can be practiced in preparation for undertaking the more sublime passive methods.