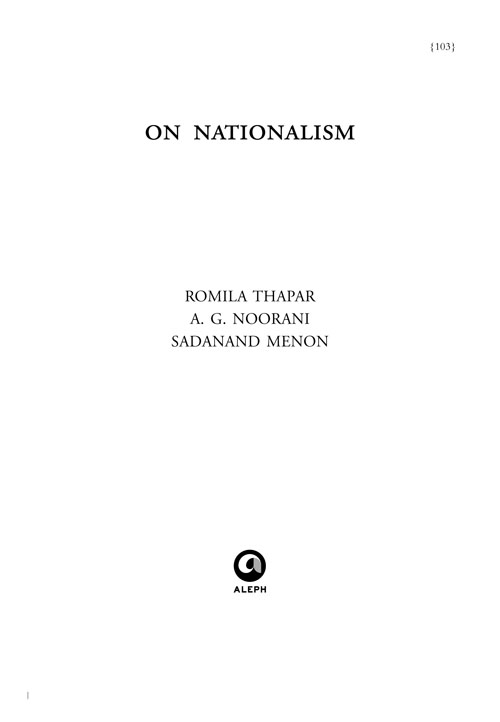

ALEPH BOOK COMPANY

An independent publishing firm

promoted by Rupa Publications India

First published in India in 2016 by

Aleph Book Company

7/16 Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110 002

Copyright Romila Thapar 2016 A. G. Noorani 2016 Sadanand Menon 2016

All rights reserved.

The views and opinions expressed in this book are the authors own and the facts are as reported by him/her which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same.

While every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain permission, this has not been possible in all cases; any omissions brought to our attention will be remedied in future editions.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from Aleph Book Company.

eISBN: 978-93-84067-75-5

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

CONTENTS

Romila Thapar

A. G. Noorani

Sadanand Menon

FOREWORD

We live in troubled and troubling times. Not a day passes without some fresh outrage being reported in the media or being talked about in our neighbourhoods. None of this is new. We live, as we have for the last couple of centuries now, in a country that is poor, violent, corrupt, overpopulated, misogynistic, unequal, and prone to sectarian violence, terrorism and environmental disasters, to name just a few of the challenges we have to cope with, and it is unrealistic not to expect bad things to occur. We all hope such tragedies will be eliminated, that we will touch greatness, but unless all those who are able to make this happen actually rise above their own selfish agendas and begin to work in concert and with tremendous dedication, it would be safe to say that for the majority there will be no radical change for the better any time soon, despite the fact that some of our countrymen work hard to make a difference. What we do have, imperfect though they may be, are freedom of expression, liberalism in some pockets, inclusiveness, cultural vibrancy, the right to practise whatever faith we choose without let or hindrance and so onthe fundamental rights bequeathed to us by our founding fathers. In recent times, though, a very vocal set of politicians, sectarian organizations, god-men, trolls and assorted thugs have begun to brazenly attack some of the values that invest this country. Never before have they been assailed with such impunity.

One of the most contested ideas in twenty-first-century India is nationalism. It is easy to see why. If the forces I am speaking of (usually right wing and majoritarian) succeed in recasting nationalism in a straitjacket that suits their own narrow ends, they will, they hope, usher in a thousand-year rule of the theocratic kind. That they will probably not succeed in their aims, given the multifariousness of their coreligionists and the tens of millions of minorities (by this I mean not only religious minorities, but everyone who has a problem with religious fundamentalism and the notion of living in a violent theocracyelse, why is every sane, secular person opposed to the likes of ISIS or Boko Haram?) who might not take kindly to becoming second-class citizens is small consolation because considerable damage will have been done to Indian society by then. We need to constantly remind ourselves that the only way for India to survive and thrive is to continue to be the open, inclusive country that our founding fathers fought to bring into being, and that all of us inherited at birth. That is why this book is being publishedto make its own small contribution to the ongoing debate. It seeks to provide interested readers with a range of thoughtful opinions on why it is important to understand what nationalism is, and why certain kinds of nationalism may be seen as true and others false.

It could be said that nationalism is subtly threaded into our DNA; it doesnt intrude upon our daily lives but makes itself manifest on demand, often when it is under threat in some way. Some years ago, my wife, Rachna, and I had occasion to think about our nationality, and the nationalism it engendered. We had just become eligible for citizenship of the country we then lived in. Our home was in a city that routinely featured in lists of the most congenial places in the world to live and work in. We had a very brief discussion about whether we wanted to adopt a new nationality. Despite the fact that the country we lived in offered some enormous advantages over our own, there was no doubt in our minds that changing our nationality wasnt an option. We were born Indian and would die Indian. Some of Rachnas reasons paralleled mine. For both of us, our decisions were based on what could be called a mix of nationalism and patriotism. George Orwell, the British writer and humanist, has an interesting way of differentiating between the two. He wrote in an essay entitled Notes on Nationalism, published in 1945: Nationalism is not to be confused with patriotism. Both words are normally used in so vague a way that any definition is liable to be challenged, but one must draw a distinction between them, since two different and even opposing ideas are involved. By patriotism I mean devotion to a particular place and a particular way of life, which one believes to be the best in the world but has no wish to force on other people Nationalism, on the other hand, is inseparable from the desire for power. The abiding purpose of every nationalist is to secure more power and prestige, not for himself but for the nation or other unit in which he has chosen to sink his individuality. Others have defined nationalism a little differently but basically it was why we decided to stick with the passport with the gilt-embossed Ashoka Chakra.

As I was writing this foreword, I was reminded of the things that went through my mind that wintry evening almost a decade ago. In sum, my decision was based on a sense of belonging to a larger community, both real and imagined, that I had inherited when I was born. This community had nothing to do with caste, creed, region, language, but rather all of these and more. It had to do with memories of my grandmothers sari, the softest garment I had ever touched (the softness of her sari was because my maternal grandparents led a middle-class life in small-town India with no frills. My grandmother only possessed a few cotton saris that had been washed often; this lent the material an extraordinary delicacy); the feeling of joy when, as students, we received news of the defeat of Indira Gandhi after the dark days of the Emergency; the sadness that enveloped us when we heard of the demolition of the Babri Masjid; the exhilaration we felt when M. S. Dhoni hit the winning six to seal Indias victory in the World Cup; the great sense of satisfaction I felt when I read and published Vikram Seths A Suitable Boy or P. Sainaths wrenching stories about Indias poorest districts; the awe I felt when I first glimpsed the most beautiful lake in the world, the Pangong Tso, in Ladakh. Underpinning all this was, of course, the decades of learning and doing, the friends, the family, the shared history and heritage. As with the good stuff so with the bad. The anger I felt over all the things that bothered me was keener when they had to do with India than any other place on earth. No other country could provide that feeling of belonging. That was my nationalism; it was the sense that I was an integral part of something much larger than myself which no one could take away from me, not now or ever. It was a concept, it was a tangible reality, and in its most abstract form it included every Indian, known and unknown, in the best possible way.