FOREWORD

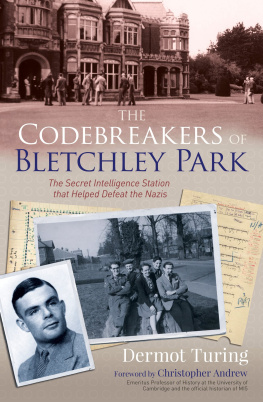

George Steiner once hailed the British code breaking effort at Bletchley Park as the single greatest achievement of Britain during 193945, perhaps during this century as a whole.

The claim will doubtless strike many as ridiculous. Surely, however precise the information about the enemy which Bletchley provided, it would have been useless without the courage of the sailors, soldiers and airmen who had to act upon it? True; nevertheless, I still think Steiners dramatic assertion is justified. While all the major combatants in the second world war had navies, armies and airforces often as good as, if not superior, to ours, none had anything to compare with our achievements in intelligence. Bletchley was Britains singular contribution, not just to victory, but to the development of the modern world.

I met my first pair of Bletchley Park veterans by accident over dinner with a friends parents in 1980, when I was twenty-three. Typically, they were the daughter of an earl, and a grammar school boy from Keighley, who had gone on to become a famous historian. By the end of the war, he had helped compile a set of records of the Luftwaffe, so voluminous they had to be housed in an aircraft hangar, and which eventually proved to be more detailed than those held by Goerings Air Ministry in Berlin. She had operated a Type-X decryption machine a simple clerical job but the nature of her work meant that, at nineteen, she held in her head the greatest British secret of the war: a fact of which she was acutely conscious, she said, every time she ventured out in public.

I listened, enraptured, to their stories, and fifteen years later wrote a novel, Enigma, which tried to convey something of the atmosphere of this haunting place, which had cut across the traditional barriers of sex and class. I had the good fortune to conduct my research at a time when some of the key players were still alive and able to answer questions: Sir Stuart Milner-Barry, former junior chess champion of Great Britain, and subsequently head of Bletchleys Hut 6; Sir Harry Hinsley, expert in signals traffic analysis, who later became the official historian of British intelligence in the second world war; and perhaps the most memorable of them all Joan Murray, one of Bletchleys few women codebreakers, who had worked on the U-boat ciphers in Hut 8, had been briefly engaged to Alan Turing, and who was now living, widowed and solitary, in a small house in north Oxford.

All these three are now dead; and the sad truth is that within the next decade virtually everyone who played a significant role in Bletchley will have gone, too. Hence the need for this book, which skilfully draws together the voices of the past. The wartime code breakers not only produced the most astonishing cornucopia of intelligence in the history of warfare (at its peak, Bletchley was decrypting 10,000 enemy signals per day); they not only pioneered the development of the computer, and so helped give birth to the information age, they also represented the triumph of a peculiarly British blend of genius, discretion, amateurism and eccentricity, which seems to be vanishing with them.

Whenever I think of Bletchley, I think of shift-changes at midnight and chilly wooden huts, of glowing orange valves and clanking electro-magnetic machinery; I think of Alan Turing cycling to work in his gas mask during the hayfever season, and of sunlit games of rounders in front of that hideous Victorian mansion; I think of chess-players, crossword-puzzle addicts, Egyptologists, numismatists, philologists, lexicographers, musicologists in short, of that particular kind of quiet, self-absorbed, recondite intellect, which is often overlooked or even mildly despised in the modern world, but which, for a few years, came together in a suburban park in the dreary midlands of England, and helped save western civilisation.

Robert Harris

INTRODUCTION

Thirty years after World War II ended, a relaxation of British Government security strictures brought to light one of its most important secrets. It was revealed, to understandable astonishment, that the war had been won not just by military genius or by the dogged courage of the Allied Armed Forces though both had of course been of vast significance but by groups of obscure or unknown people who found out in advance what the enemy intended to do, and passed on this knowledge to those who commanded the armies, the fleets and the bomber formations. Vital information that turned the tide of battle in the North African desert or on the Pacific Ocean proved to have been obtained not by the skill and bravery of spies, or by miraculous coincidence, but by the plodding and unglamorous work of operatives who read the enemys coded messages. The result has been, of necessity, a re-evaluation of reputations and a rewriting of history.

The ability to gain access to the very thought processes of the enemy was a major epic of ingenuity, and a great adventure. What makes it even more remarkable is the fact that the people who carried it out (and there were thousands of them) received no public recognition for their contribution to the war effort, and were forbidden to tell even their families what they had been doing throughout the long years of conflict. Without a single known exception, they faithfully kept this silence until, an entire generation later, they were permitted by the government to admit their involvement. The story of these cryptographers has considerable bearing on our own postwar world, for in the process of breaking the secret codes of Nazi Germany they created the computer as we know it today.

The breaking of German codes began long before the start of war in 1939. For almost a decade, cryptanalysts in Poland had studied and replicated the Enigma machine, which was used by German armies from the 1920s until Hitlers defeat. Thanks to their skill and perseverance the Western democracies, France and Britain, were in possession of working copies of Enigma by the time hostilities began. Though Poland itself was dismembered and conquered, it was thus able to make a contribution to eventual victory that was beyond calculation.

As for the Axis powers, it was fortunate that they took a view of cryptography that was both disdainful and complacent. By tradition, the German military mind did not approve of, or appreciate, such skulduggery. Throughout the war, senior officers therefore sometimes ignored opportunities to make use of intelligence that could have been of value. They also largely took it for granted that their communications were secure, and left it at that.

Their greatest disadvantage of all, however, was the nature of Adolf Hitler. Having grown accustomed to a sense of his own infallibility, the Fhrer saw no need to waste time or effort on cryptanalysis, and with few exceptions he failed to take it seriously. He had, after all, conquered Europe by relying on his own hunches. Swift and decisive action, not painstaking intelligence gathering, was the key to success. Hitlers entourage, and his General Staff, could not have retained their positions without sharing, at least publicly, this belief in his genius and thus by implication regarding intelligence as unnecessary. The Fhrer was provided, by several organizations, with a great many decrypted Allied messages. These were often highly informative. Hitler, however, committed a classic error by failing to read them objectively. His mind already made up, he would dismiss data that did not fit with his views. He once scrawled across a dossier dealing with Soviet economic recovery the comment: This cannot be. It probably did not, in any case, help the German cause that Admiral Canaris, the head of the