While Berlin Burns: The Diary of Hans-Georg von Studnitz 19431945

This edition published in 2011 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Limited,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire S70 2AS

www.frontline-books.com

Email: or write to us at the above address.

Foreword Andreas von Studnitz

Introduction Roger Moorhouse

Copyright Hans-Georg von Studnitz

ISBN: 978-1-84832-617-0

Digital Edition: 978-1-78340-401-8

The right of Hans-Georg von Studnitz to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

P UBLISHING H ISTORY

While Berlin Burns was first published in the USA by Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffe, New Jersey in 1964. This edition includes a new foreword by the authors son, Andreas von Studnitz, and a new introduction by Roger Moorhouse

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

Typeset in 10pt Minion by

Mac Style, Beverley, East Yorkshire

Printed in Great Britain by CPI

Foreword

My father was the eldest of four brothers, all of whom died during the Second World War, so when I was born I became his whole life. My father was, as you say in German dancing on two wedding parties. One half of him took part in the social life where he came from: aristocracy. The other half broke out, looking for something else. So he became a journalist in his early twenties after some years of hanging around in South America as a banking apprentice. Like many fathers he wanted me to avoid the mistakes he had made in his youth and was very glad about my first intention to become a banker. Great was his disappointment when I had to tell him, No Dad, Im going to study law. He was shocked when I decided to break up with that too and go to the theatre, first as an actor and then later as a director. On my thirtieth birthday (at that time I was working in a little theatre in Germany, in the middle of nowhere) he asked me whether I was happy with what I was doing, to which I assured him, I was. He responded with, Because I think, if you stay mediocre you wont be happy.

Lucky for him that he had the chance to prove the contrary...

When I first read my fathers book While Berlin Burns, it must have been between 1980 and 1990. He already was older than seventy-five, me in my thirties. The reason was the question coming up in me again: How exactly was life for you during the Third Reich and what was your work as a journalist for the press department of the German foreign office during the last years of the Second World War?

In many conversations about that subject with my father, I always had the impression of a man, to whose attitude towards German fascism the term inner emigration made sense. In the way that he, a konservative, patriotically thinking writer (who in his autobiography Seitensprnge, wrote: I would have preferred to live in the nineteenth than in this barbaric century and I still consider monarchy as the best form of government) was hoping for better times after the war, in which the German people would overcome Hitler and renew itself by own power.

While Berlin Burns is a document of this inner emigration and his loneliness in the years 194345. Since he was monitored like everybody in similar positions by the Gestapo, the only place to keep the manuscript safely while he was writing it, was in his office in the ministry of foreign affairs. The only person who knew about it except him was his secretary. She kept these lines (which, in their dry way of stating what was happening every day, including the latest Hitler-jokes and the short information that, in the foreign press, for the first time KZs were mentioned) in the official safe of the press department. There nobody would search them.

While Berlin Burns was my fathers first book and the only one which was also published in English. I am very glad about this new edition in memory of my father.

Rimsting, August 2011

Andreas von Studnitz

Introduction

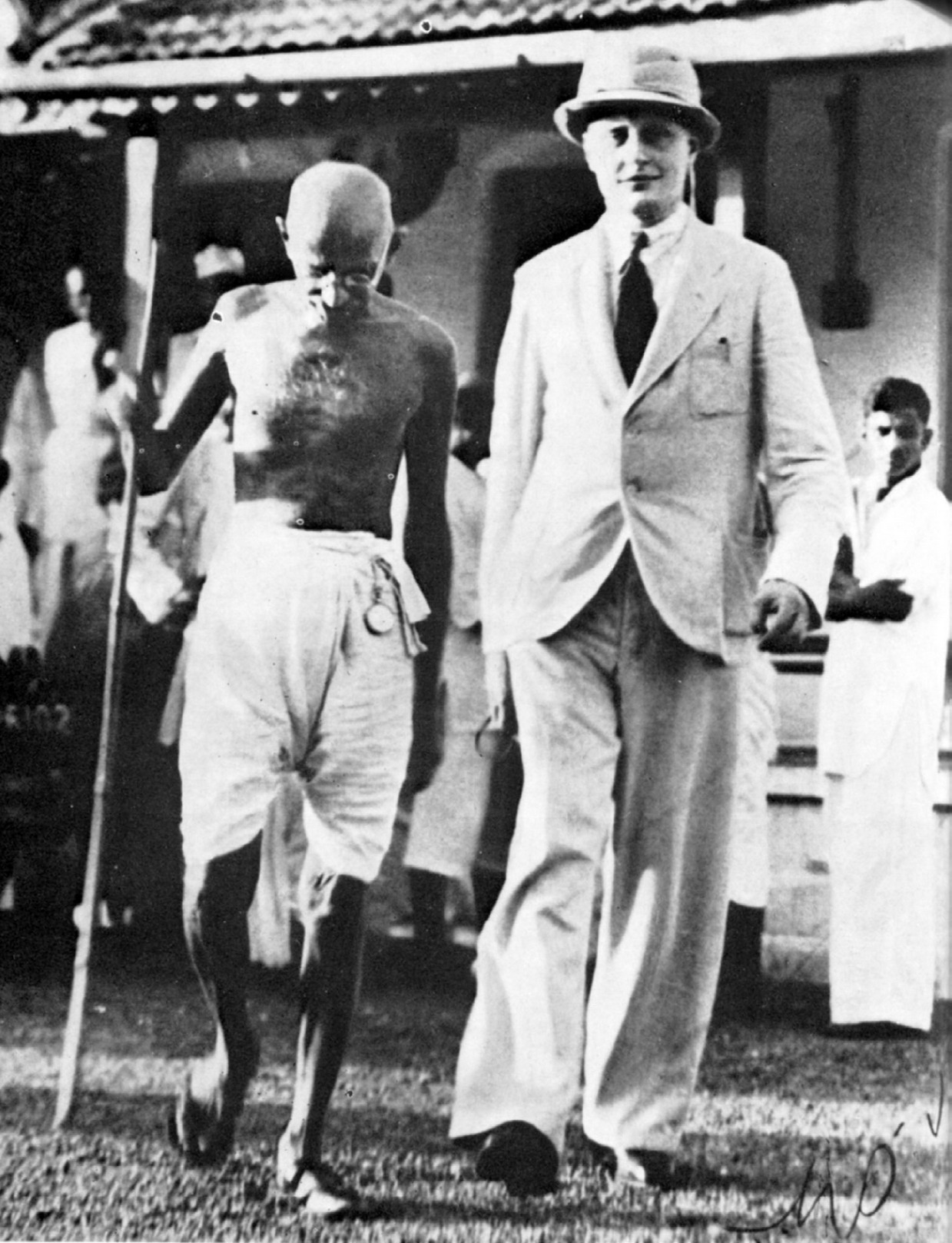

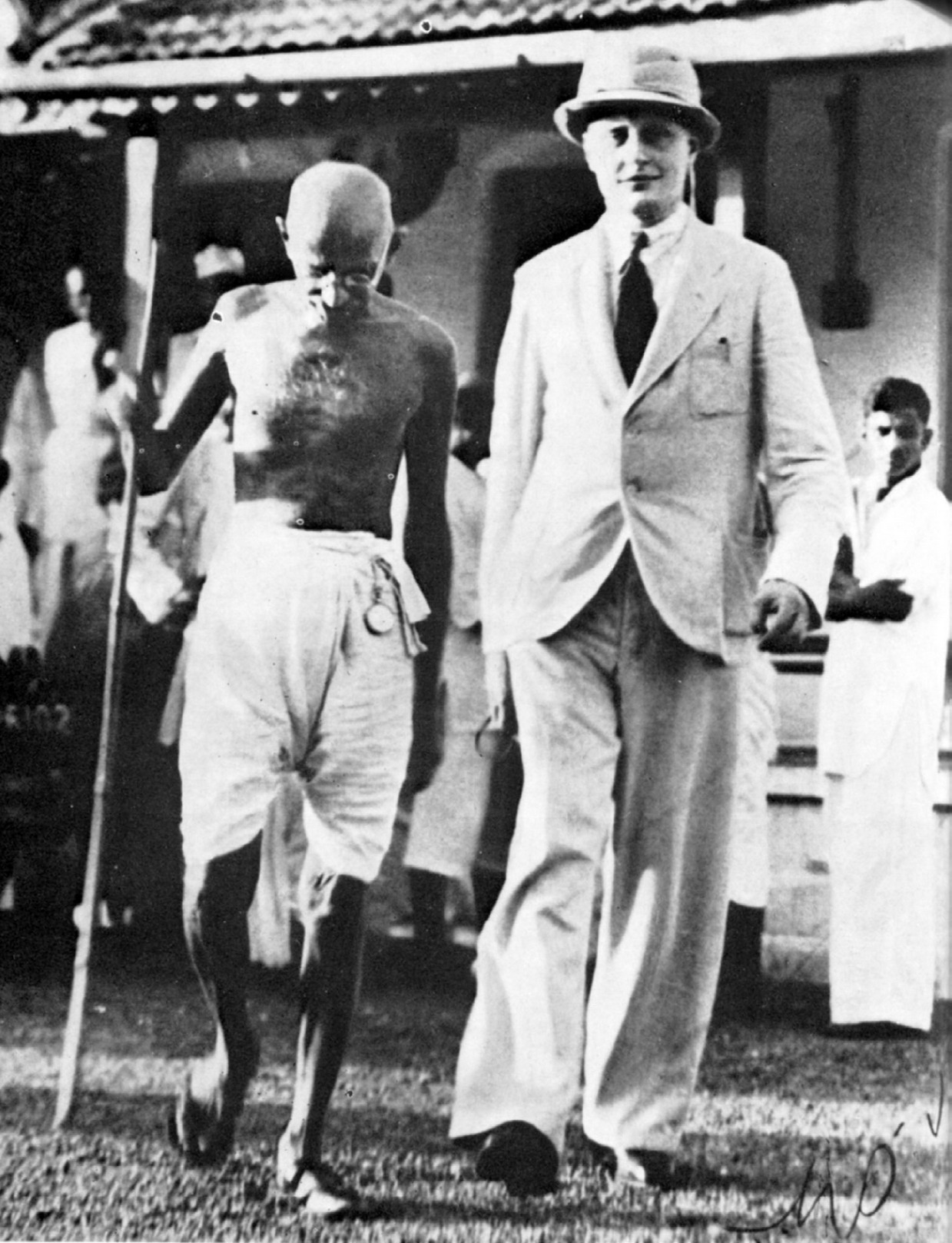

Hans-Georg von Studnitz was born in Potsdam in 1907. Of old Silesian aristocratic stock, he initially trained as a banker and worked in the Americas in the late 1920s, before returning to Berlin as a young man in 1929. Switching to journalism with the onset of the Depression, he would again travel widely, spending most of the 1930s as a foreign correspondent for the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, reporting from various European capitals, as well as India and the Middle East, and covering the Spanish Civil War.

Like many other journalists of his era, Studnitz was engaged by the German Foreign Office with the outbreak of war in September 1939, where he was given the task of preparing articles for the domestic press and monitoring the reports of foreign journalists. In the autumn of 1940, he then shifted to the Press Department of the Foreign Office, where he was responsible primarily for writing daily political reports for German embassies and legations abroad. He would remain there until the end of the war.

At some point in those interesting times, Studnitz started to keep a diary, to record as he put it; a critical survey of a moment of history. That diary loyally transcribed and concealed by his Foreign Office secretary would form the basis of this book: While Berlin Burns. Opening with the fall of Stalingrad in February 1943, it is Studnitzs personal account of the final two years of the Second World War; the story of the collapse of Hitlers Third Reich, and of the violent humbling of his once-proud capital city.

Unlike many commentators of the era such as Ruth Andreas-Friedrich or Missie Vassiltchikov Studnitz was not what one might describe as an innocent bystander or an opponent of the Nazi regime. Rather, as one of the leading members of the Foreign Office Press Department, he was a man of considerable influence, and a key player in the politics of propaganda within the Third Reich. A Nazi Party member from 1933, Studnitz had quickly proved himself to be an adept propagandist, penning a number of articles and brochures for the Nazi press, usually under a pseudonym, alongside his regular work in the Foreign Office. In this capacity, Studnitz would parrot many of the well-worn Nazi slogans and would wax lyrical in print about the historical perfidy of the British, the wanton materialism of the United States or the revanchism of the French, pausing only to laud those nations that had allied themselves to Nazi Germany, as the shining representatives of western Christian culture.

For all such utterances and allegiances, however, it seems that Studnitz did not quite view himself as a Nazi. He certainly does not come across in his diary as an ideological animal, thereby leaving the reader to wonder whether he was careful with the thoughts that he committed to paper, or whether he assiduously edited himself prior to post-war publication. On this particular point, the wider record is silent, but it is quite possible that the Studnitz revealed in the pages of this diary is the real one, and the pontificating ideologue of the press was a career-driven affectation.