Copyright 2020 by Jonathan Lichtenstein

Cover design by Julianna Lee

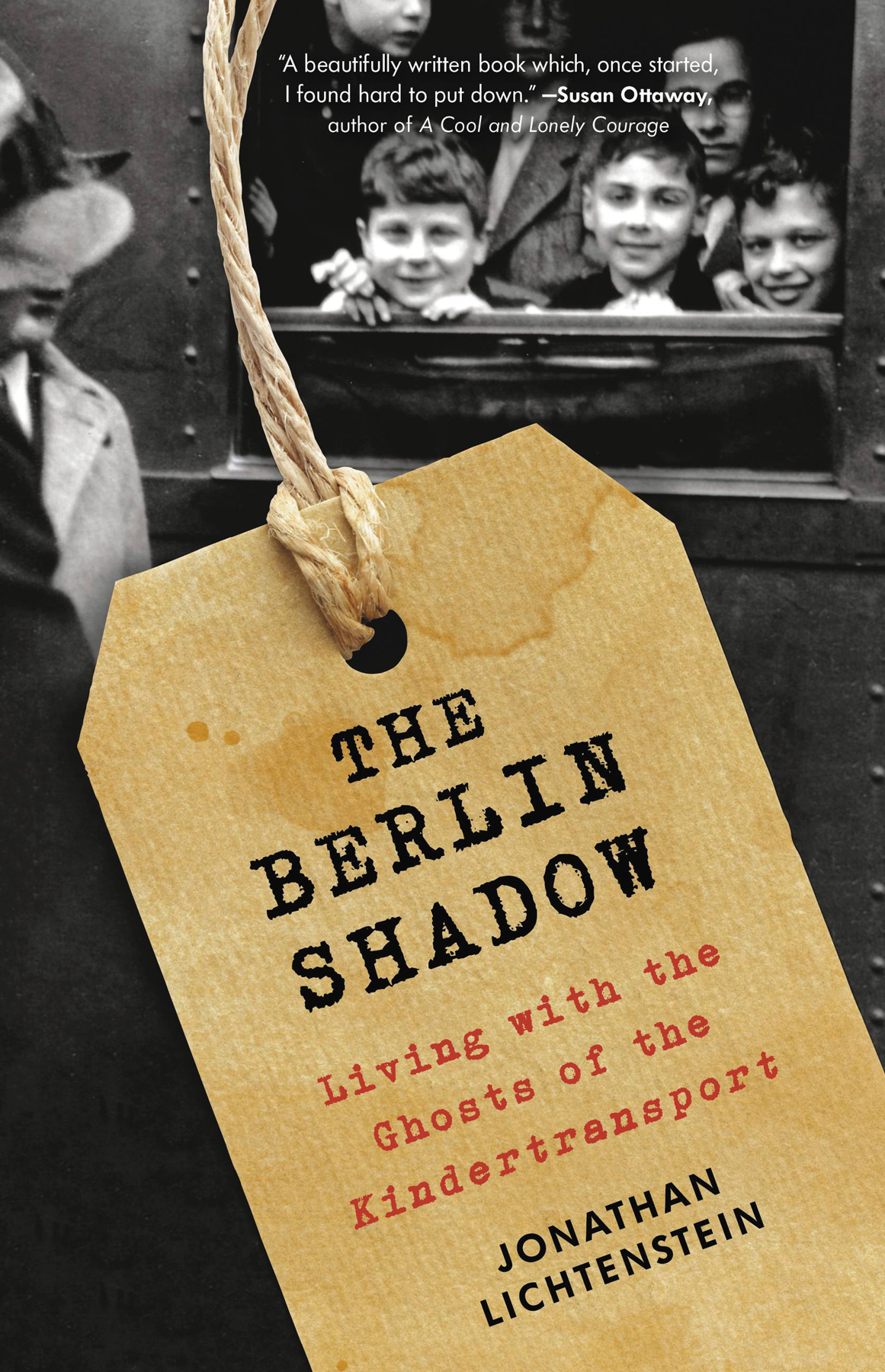

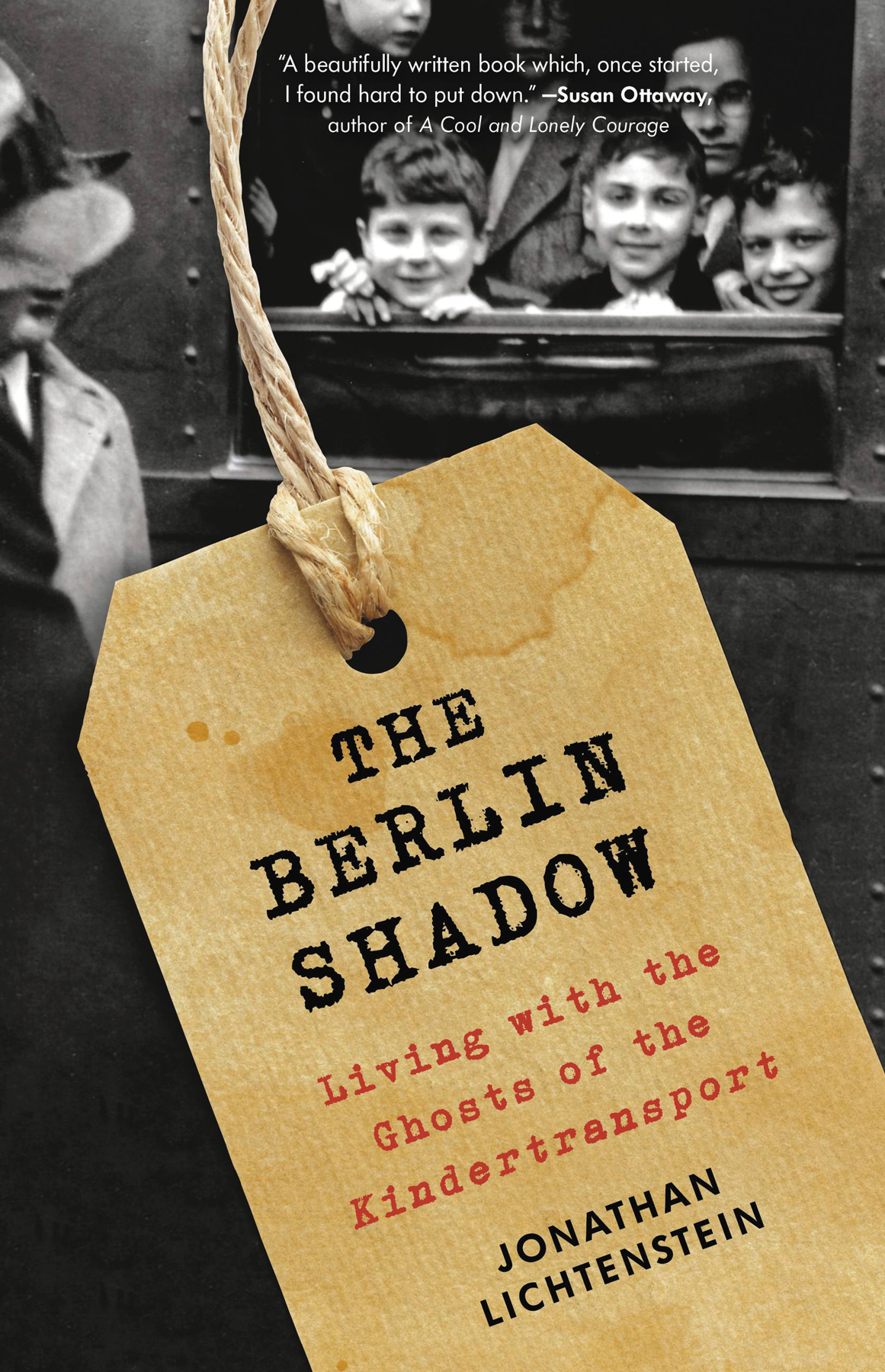

Cover art: AA Film Archive / Alamy Stock Photo (children on train); Getty Images (tag); Shutterstock (aged paper)

Author photograph by Joe Lichtenstein

Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown Spark

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrownspark.com

twitter.com/lbsparkbooks

facebook.com/littlebrownspark

Instagram.com/littlebrownspark

First ebook edition: December 2020

Originally published in the United Kingdom by Scribner UK, August 2020

Little Brown Spark is an imprint of Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown Spark name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-54099-5

LCCN 2020943058

E3-20201111-JV-NF-ORI

For Joe and Freddie and Rosa

The Kindertransport (Childrens Transport) was the informal name given to the rescue effort that brought unaccompanied refugee children to Great Britain between 1938 and 1940. Approximately 10,000 children made the journey from Germany, Poland, Austria, Holland and Czechoslovakia. Most were Jewish. One of the children who made the journey on his own, aged twelve, was my father, Hans Lichtenstein.

I ring. He answers.

You want to go?

Yes.

He falls silent. Theres a long gap.

The trip might help you sleep.

I doubt it.

How is it?

What?

Your sleep?

He falls silent again.

It must be alarming.

What?

Not being able to sleep.

Ive never been able to sleep.

Perhaps the journey will help your nightmares.

Perhaps it will make my nightmares worse.

But you want to go?

Yes.

And so I organise itthe trip: the dates, the ferry, the tickets, the car, the route, the passports, the hotel. Later I ring again.

Were going to do your original journey in reverse.

In reverse?

Were going to go backwards.

Backwards?

Were going to go to Berlin from here. Then well come back.

But I didnt go back.

I know that.

Mine was a one-way ticket.

He laughs.

I want to try to find where my fathers shop was.

Of course.

And my fathers grave.

Yes.

And the station?

The station too.

There. It has been agreed. I will walk the pavements with him. Together we will breathe the air of the city that ripples its past through his daily life and the corners of his childrens lives, the rivulets of its history draining into us, the gutters carrying the rain and wash of its streets, its twisted papers, its yellowed stars, its broken glass, its ash, his fathers grave. The station. The shop.

For many years I had wanted to travel with my father to Berlin in order to trace the route of his escape on one of the Kindertransports. However, the fragility of our awkward and distant relationship had made the arrangement of such a journey impossible. The thought of spending days and nights together in close proximity appealed to neither of us for we both understood that such a trip could break the small amount of fondness that had only recently arisen between us. As well as this we both knew that during such a journey my father would be forced to confront a series of darknesses he had kept, for his whole life, close to his chest. And we knew too that the illumination of these darknesses might well precipitate in him an overwhelming despaira despair, he had confided to me on more than one occasion, I might never recover from.

Nonetheless, as an old man, and after a debilitating illness that had begun to temper his fitful spirits, he agreed to make the journey in order to confront the event that had dominated his life. Though I had only recently begun to realise it, the event had come to dominate my life toothrough my endless and repetitive cycles of a brooding need to be away from all people; an occasional, vivid and saturating experience of elation; a propensity for a violent and unsettling anger; and extreme productivity followed by months of a grey, undifferentiated torpor as well as a bleakness so frightening at times I did not want to remain alive.

Initially we chose the date of the return journey in order to mark the anniversary of my fathers departure from Berlin, which he maintains was six weeks before Britain declared war upon Germany and was one of the last Kindertransports out of Berlin. However, due to an illness that befell him that summer we settled instead on the anniversary of Kristallnacht. This was because a photograph had been found that showed his fathers shop pictured after it had been smashed and looted during this catastrophic event. My father wanted to try to find the site of this shop, to see whats there, if anything. He also wanted to visit his fathers grave located in the Jewish Weiensee cemetery. He had never visited his fathers grave, not even as a child. He had been kept away from his fathers funeral and did not know that his fathers death was by suicide until many years after the war had ended.

My father could not bring himself to tell me that his father had committed suicide until my eighteenth birthday. That day he made the announcement to me while we were driving together through the Welsh hills towards Cefnllys. The news arrived from out of the blue.

Now youre eighteen I have something to tell you.

What?

My father committed suicide.

Did he?

I dont want to talk about it.

How?

Shut up.

But

I said shut up.

And so we carried on driving, him at the wheel, revving the engine, tyres whining, his attention on the bends of the road, the car leaning at precarious angles as he took the corners at speed, trimming each apex, bumping over cats eyes, all four tyres about to lose their grip, the Welsh hills surrounding us.

Cae Hyfrydd was a dark house and full of ice in winter so that in the mornings the thin glass of the windows was crazed with frost on the inside and occasionally strange noises passed through it during the night. It had high stairs, which curved, and an attic. It was our new semidetached house on Pentrosfa, the unmade road that rose steeply from Wellington Avenue. Pentrosfa was a road that was different from any I had experienced before; bumpy and cratered and wide. It exuded space and looking out from the window of our front room the other side of the road seemed far away. When the Evanses son wheeled out his metallic green BSA motorbike from his parents garage on the opposite side of the road and, hurling his weight onto the silver lever at its side, kick-started it into life, it was as though he had emerged from an exotic land, a world of detached bungalows with lawns and trimmed hedges, of white gates, of front doors with stained glass; an architecture of permanence and reliability.