Published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by

OXBOW BOOKS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

Oxbow Books and the individual contributors 2017

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-676-9

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-677-6 (epub)

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

to be inserted

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Printed in to be inserted

Typeset in India by Lapiz Digital Services, Chennai

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

| UNITED KINGDOM | UNITED STATES OF AMERICA |

| Oxbow Books | Oxbow Books |

| Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449 | Telephone (800) 791-9354, Fax (610) 853-9146 |

| Email: | Email: |

| www.oxbowbooks.com | www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow |

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

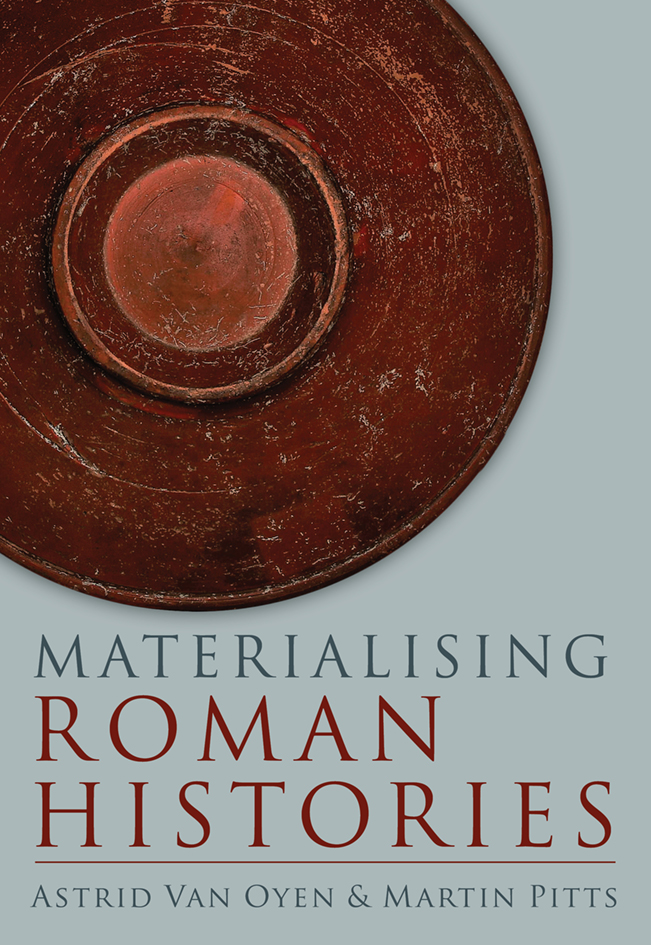

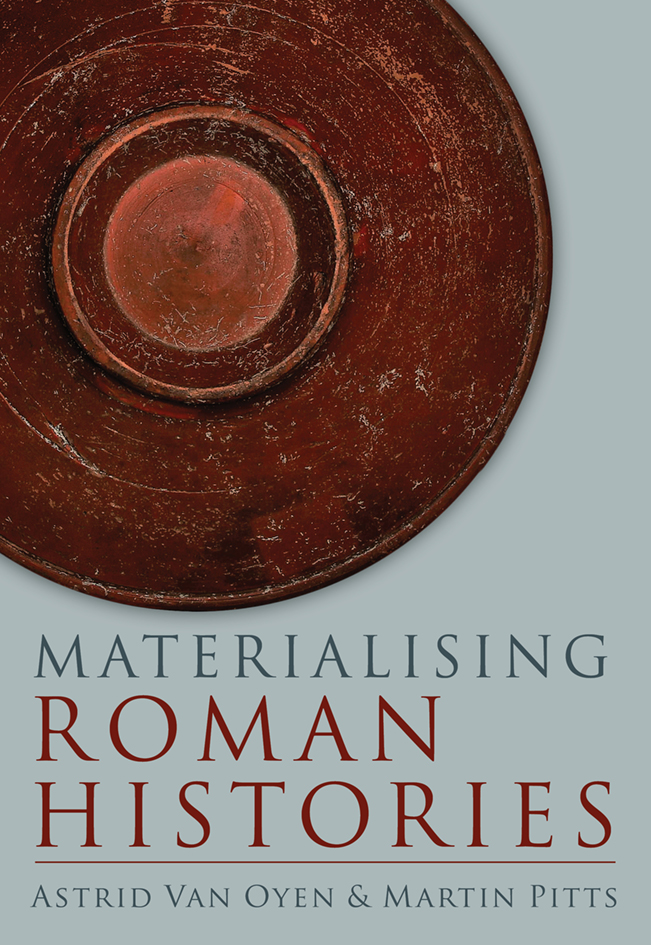

Front cover: Terra sigillata dish. Image courtesy of Judith Bannerman and Jacq Christmas

(University of Exeter).

Back cover: to be updated in due course

Contents

Astrid Van Oyen and Martin Pitts

Hella Eckardt

Rob Collins

Martin Pitts

Martin Millett

Alicia Jimnez

Jeroen Poblome, Senem zden Gereker and Maarten Loopmans

Elizabeth A. Murphy

Robin Osborne

Astrid Van Oyen

Ellen Swift

Eva Mol

Miguel John Versluys

Andrew Gardner

Greg Woolf

Preface

This volume explores the role of material things in shaping Roman histories. Different conceptual and methodological tools can be brought to bear on this question, but no example proves the basic point as well as the story of the genesis of this book. At first sight, the key ingredients for a project like this appear to be limited to people and ideas: one needs a stimulating question, a line-up of bright scholars, and a toing and froing of new ideas. These elements were definitely part of the cocktail of the 2015 Laurence Seminar at the Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge, and of a session at the Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference (TRAC) at Kings College London two years earlier, both organised by the editors. And yet, no seminar or volume was ever made from the mere combination of the aforementioned ingredients. What is missing?

Minds alone do not speak to one another directly, and not even the digital revolution has done away with the need to bring people together physically. Agendas need to be aligned, trains booked, and rooms reserved. These are not just practical trivia, subordinated to the real business of intellectual exchange. For true discussion to be had and intellectual progress to be made, the atmosphere needs to be at once collegial and critical, and imbue participants with the right state of mind. Indeed, the setting directly acts on the mind. In a similar vein, ideas need to be fed, hydrated, and rested. We can therefore state that without the generous financial support of the Faculty of Classics and the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, not only would this volume not have been made, the ideas expressed in it would not have taken shape.

The fundamental role of the material setting and its inherent contingency mean that the development of ideas is never a case in which one plus one equals two. Instead, as the trajectory of this book unfolded, starting assumptions were challenged, new questions emerged, and routes mapped out in advance were travelled only in part or diverted. These transformations not only affected ideas, but also the very line-up of participants. The original TRAC session included a paper by Ros Quick, and seminar contributions by Hilary Cool, James Gerrard, and John Robb did not end up in the volume, but have nevertheless shaped it in no small measure. Conversely, Astrid Van Oyens chapter was written after the seminar, and while Elizabeth Murphy was not present at the Laurence Seminar, her contribution to the volume adds a much-needed micro-scale perspective to the whole.

For the eventual publication of this volume, we are grateful for the financial support of the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, for the editorial guidance of Clare Litt at Oxbow Books, and for the comments of two external peer-reviewers. For all its emphasis on things redressing a long-lost balance this volume emphatically does not deny the essential contribution of human agency. Our biggest thank you, in the end, goes to the participants in the seminar and the contributors to this volume, for expanding our horizons and those of Roman archaeology, and to the reader who has picked up this volume, for joining the exciting dialogue that is Roman material culture.

List of figures

List of tables

Introduction

Chapter 1

What did objects do in the Roman world? Beyond representation

Astrid Van Oyen and Martin Pitts

The problem with representation

Archaeologists often remark on the massive and widespread changes in the material environment in the Roman imperial period. There were more things around, which impacted on the lives of the many as well as the privileged few. The volume of traded goods increased, networks of circulation expanded, and local production intensified (e.g. Greene 2008; Bowman and Wilson 2009). With quantitative increase came qualitative innovation. Objects became ever more differentiated in terms of style and function. For many communities, especially in northern and western Europe, the Roman period heralded the first appearance of genuinely standardised material culture, as opposed to objects that belonged to a more generally shared stylistic continuum. Despite the deep and far-ranging implications of these observations for current understandings of the Roman past, there have been relatively few attempts to explain or come to grips with their implications (a notable exception is Wallace-Hadrill 2008). Inquiries into the causes of such profound material changes have often involved methodological leaps of faith, connecting the plethora of new objects and styles to top-down models of imperialism, economic growth and Romanisation. But behind these empirical observations lurks another historical question: what were the historical consequences of these changes in the material environment? Did these changes actually alter peoples relations to things, and through this, to each other?

In order to address these questions, we believe it is necessary to free up conceptual space to reconsider the issue of how we write history from artefacts. The culture-historical equation between pots and people that underpinned (for example) the earliest models of Romanisation is now rightly frowned upon. From changes in artefacts and assemblages we cannot confidently deduce the arrival of new people (e.g. Eckardt 2014). We argue that in the wake of the discredited culture-historical paradigm, Roman archaeology has neglected the opportunity to rethink its model of material culture. Instead, it has merely refined a representational approach: if objects no longer represent people, they have come to stand for or reflect motives external to them, such as status or other facets of group identity.

Next page