Table of Contents

on

to

My father, Brigadier Hardit Singh Kapur,

My mother, Lajwant Kaur

Who told me many enlihtening stories

and to

My husband, Payson R. Stevens,

Without whom this book

Would never have been

AUTHORS PREFACE

For half the year, every year, my husband and I live in a remote valley in the Kullu district of the Himalayas in India. The region is called devbhumi, the earth of the gods, or more commonly, Valley of the Gods. Indias mythic past is present here, pulsing and alive in the names of trees, rivers, villages, and temples.

Ubiquitous in this thousand-year old forest is the Cedrus deodara, cedar, or deodar, divine wood, tree of the gods. The stream that flows in front of our house is named Hirub, after Hidamba, one of Bheems wives, sister of a demon that he slew. Bheem is one of five Pandava brothers, the heroes of the great Indian epic, the Mahabharata.

The temple in the village after which the stream is named, and which is an hour of vigorous hiking away from our home, has a temple dedicated to Panch Vir, the five heroes of the epic. The temple in our own little village is dedicated to Boodhi Nagan, Old Serpent Woman, who is said to have hosted the five brothers in their exile. Vishnu Narayana, Shiva, and Kali also have their temples in the area. At least three or four times a week, loud horns and drums announce a peregrinating god or goddess on his or her visit to other temples or villages to attend a marriage or bless a new birth, a new house, a wedding, or a retirement. The particular god or goddess is represented by a brass mask under a canopy of silver, atop a palanquin decorated with brightly colored scarves of silk and satin, bordered with gold, and adorned with brilliant local flowers.

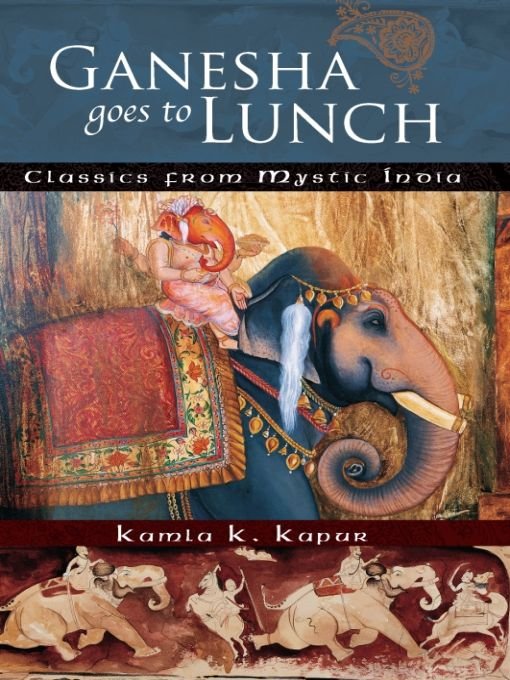

What is found in this valley is an intensified reflection of that mythic connection that is strong even in urban India. The majority of the Hindu population is actively engaged with mythic practice. It is not uncommon to see naked, ash-smeared sadhus, disciples of Lord Shiva, walking barefoot on the roads, a python around their necks, or even riding motorcycles, matted locks flying. Even the more staid believers worship gods from mythology. The names of God are the same as the names of characters from the epics: Krishna, Shiva, Vishnu, and Rama. Men, and women too, are named after these gods. Many national holidays are dedicated to Shiva, Ganesha, and Krishna. Even large corporations carry ads in the papers: Happy Birthday, Krishna! Pictures and statues of Ganesha are found on websites, wedding cards, invitations to and announcements of marriages, births, and birthdays. Plastic, stone, and clay images of these gods adorn dashboards of cars, entrances to shops, restaurants, homes and offices. In the countryside too, in fields and forests, under trees, over roofs, in caves, and by roadsides, statues of gods have their dwellings.

India has a vast and inexhaustible storehouse of mythic stories. I say inexhaustible because there are manifold versions of each myth. The oral beginnings of mythology ensured that there were very few authorized and definitive originals. Over the centuries there have been additions, interpolations, revisions, and accretions that have swelled the streams of stories to rivers and oceans. Then again, each of the many regions and languages of India has adapted the myths to its ethos, with the result that the same myth is so substantially different from one version to another as to constitute an entirely new story. Indias tradition of anonymous creativity has further added to the storehouse without leaving any trace of authorship.

Even today, holy men continue to take strands from the epics and spin parables from them to instruct and illuminate their congregations: undoubtedly the story of the toad from the Ramayana, herein retold, or the two stories, Blind Hunger and The Bird Who Fought War, from the Mahabharata, told to me verbally and of which I have found no mention in my extensive research, fall in this category. It would not be too far-fetched to say that Indian mythology is a work in progress, still being evolved. It is this undiscovered treasuretrove of written texts and oral tradition that makes the study of Indian myth bewildering and rewarding.

More than in any other culture I know, myth is alive and well in India. What is in-your-face here is a reminder of the hidden truth that myth has informed all the cultures of the world; that it is, in fact, the root of all religion, spirituality, and art. The mythology of the worldas Joseph Campbell, the great popularizer of myth in the twentieth century, has taught usis essentially one shape-shifting story. The global village is deeply linked, as our etymologies and a great deal of other evidence manifest. One has but to look at the root of, say, the word deodar, to see the invisible meta-reality that links us all, like the subterranean, entwined roots of a dense forest: Germanic, Old English, Old Norse, Sanskrit, Latin, and Avestan myths and words are inextricably interconnected.

To use another metaphor, the mythology of the world is one gem whose manifold facets are created and polished by different cultures. The myths of every culture illumine aspects of the same essential mystery. Western mythology, as the works of Jung, Freud, and countless others have revealed, illumine the dark recesses of the mind, and offer deep, psychological insights into the human psyche. The aspect that Indian myth brings to the surface of consciousness is, predictably, the spiritual and philosophic.

All mythic stories that are not mere fanciful and primitive explanations of natural phenomenon exist at the interface between form and the formless, matter and energy. As a vessel is necessary to contain shapeless water; as a book, words; as sound, meaning; images, or masks, as Campbell calls them, concretize the abstract mystery of life. While all mythor for that matter, all artgives form and substance to that one, formless energy that manifests as life within and around us, Indian myth in particular has a genius for clothing the infinite in human form, as Eknath Easwaran puts it in his book, The Thousand Names of Vishnu. The function of many Indian myths is to take us through duration, through the conflict and turmoil of the secular, melodramatic, human story, to the timeless, eternal beyond, the faceless and imageless source, the beginnings and endings of our terrestrial journey.

It is easy to see how Indian myth has become the repository of all our wisdom and solace. The gods, like us, are all perishable, yet timeless, like Vishnu asleep on the primeval ocean, appearing and disappearing in his incarnations like bubbles in the river of time. There is in the threads of these narratives a deep and unshakeable conviction of the deathlessness of all that is. The animate and inanimate world is formed out of the same indestructible energy. The myths seem to say to the doubting, earth-bound self, that the plasma that created all of us is, as we move through our often tragic and joyful journey, permeable to prayer. For how can a universe that has created in humans their most intense longing for the divine within and around them, thwart it? It is this assurance, so plainly and convincingly demonstrated in the stories, that makes them the hypostasis of this culture, and invites the fascination of others, the West in particular.