GEOGRAPHY

DANNY DORLING joined the University of Oxford in 2013 to take up the Halford Mackinder Professorship in Geography. He was previously a professor of geography at the University of Sheffield. His recent books include co-authored texts The Atlas of the Real World: Mapping the way we live and Bankrupt Britain: An atlas of social change and sole authored books, Injustice: Why social inequalities persist, The 32 Stops and Population Ten Billion.

CARL LEE has taught geography for the past twenty-five years at GCSE, A level and in higher education. He has written The Urban Challenge (with Graham Drake) and Home: A Personal Geography of Sheffield. His latest book is Everything is Connected To Everything Else. He has made several short films about geographical issues. He currently works as a tutor in the Department for Lifelong Learning at the University of Sheffield.

ALSO BY DANNY DORLING AND CARL LEE

Carl Lee (with Graham Drake), The Urban Challenge, 2000

Danny Dorling (with Mark Newman and Anna Barford), The Real World Atlas, 2008

Carl Lee, Home: A personal geography of Sheffield, 2009

Danny Dorling, Population 10 Billion: The coming demographic crisis and how to survive it, 2013

Carl Lee, Everything Is Connected To Everything Else, 2015

Danny Dorling, Injustice: Why social inequality still persists, 2015

GEOGRAPHY

DANNY DORLING

&

CARL LEE

Maps by Benjamin D. Hennig

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Text copyright Danny Dorling and Carl Lee 2016

Maps Benjamin D. Hennig, www.viewsoftheworld.net 2016

The moral right of the authors has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright holder and the publisher of this book.

All reasonable efforts have been made to obtain copyright permissions where required. Any omissions and errors of attribution are unintentional and will, if notified in writing to the publisher, be corrected in future printings.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 78283 196 9

Maps by Benjamin D. Hennig, University of Oxford

Text design by Jade Design www.jadedesign.co.uk

CONTENTS

We would like to dedicate this book to the thousands of geography students who, over more than two decades in classrooms, lecture theatres, field trips and tutorials, have helped us learn so much more about a subject that we love than we could have ever learned alone.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As always, we stand on the shoulders of others (or at least look over their shoulders) for all our ideas. Maybe one day we will have a big idea of our own, but we doubt it. Particular thanks must go to Michael Bhaskar, who was able to understand the original idea for this book, which was conceived on the le de R in the summer of 2014 and finished in the Jura Mountains in the summer of 2015. Thanks also to Mike Jones and Cecily Gayford for editing the text and, before it reached that stage, Grant Bigg, Tony Champion, Paul Chatterton, David Dorling, Alan Grainger, Sally James, Karen Robinson, Natasha Stotesbury, Laura Vanderbloemen, Jenny Watson and Robert Whittaker, who all provided invaluable commentary, much of which we heeded and some we possibly should have but did not.

An inspiration to us both is the work of Benjamin D. Hennig, and we thank him for permission to use his innovative cartographical skills in producing all the new maps included herein.

MAPS

INTRODUCTION

What you know you cant explain, but you feel it. Youve felt it your entire life, that theres something wrong with the world. You dont know what it is, but its there, like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad. Morpheus.

The quote is from The Matrix, a movie, not reality or is it?

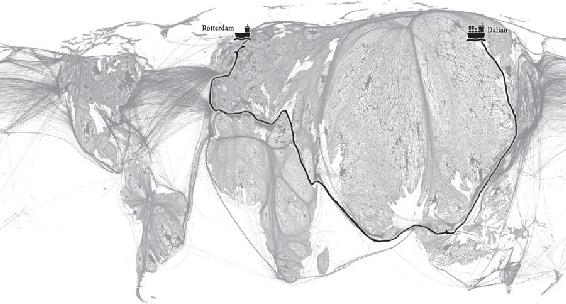

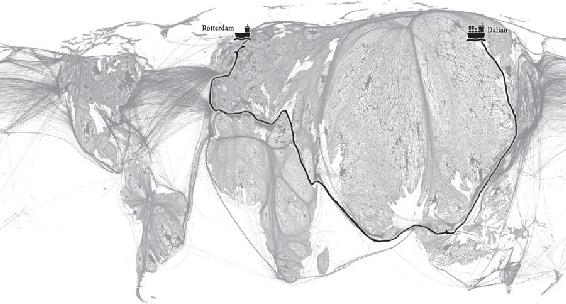

On 25 January 2015 the MSC Oscar, a Panamanian flagged ship laden with goods, set sail from the port of Dalian in China. Sailing southwest, it picked up yet more cargo at one of the worlds largest ports on the southern tip of Malaysia, Tanjung Pelepas. Next, cruising at a sedate 26 kilometres an hour, it passed through the Malacca Strait, the Suez Canal and the Strait of Gibraltar. The entire voyage to Europe took just over five weeks. On 3 March 2015, when it arrived in Europe at Rotterdams huge container port, the ship made the news. It was nearly 400 metres long, 60 metres wide and 73 metres high. It could transport 13.8 million solar panels or 1.15 million washing machines or 39,000 cars. The MSC Oscar was the worlds largest container ship.

It almost certainly isnt the largest container ship today. When the MSC Oscar was launched keels were already being laid down in the shipyards of South Korea for ships that will by now have surpassed even her 19,224-container load. A container is often referred to as a 20-foot equivalent unit (TEU), a unit designed to be hauled by a lorry. Try to imagine almost 20,000 lorries travelling end to end. Even closely packed in a traffic jam, the cavalcade would be over 160 kilometres (about 100 miles) long. The MSC Oscar is the physical embodiment of a globalised world. Its much-heralded fuel efficiency and relatively slow cruising speed are signs of recent greater concern over the environmental impacts and costs of transporting the multitudinous manufacturing bounty of China and its neighbours for the 12,569 nautical miles that separate Dalian from Rotterdam.

This map of the world has been resized to represent where humans currently live on earth by giving each person equal prominence. The largest cities can be seen, and deserts and the polar north almost disappear. This map also shows how the world is connected via the shipping lanes, flight lanes and underwater cables that carry most of the trade that drives the global economy. The route of MSC Oscars first voyage from Dalian, China, to Rotterdam, Netherlands, via Tanjung Pelepas, Malaysia and the Suez Canal is shown. This journey took 36 days, with the ship passing close by nearly half the planets human population in that short time.

The value of goods transported from China to Europe is an integral part of an equalising movement of wealth from West to East that has been one of the most dramatic economic developments of the early years of the 21st century. Goods flow from East to West, but now far more money than ever before has to flow back in recompense. The wealth of China continues to rise more rapidly than that of most of the rest of the world, while that of almost all of Europe has fallen in recent years. Yet still the ships come ever newer, bigger and better full to the brim with the stuff of consumption.

The MSC Oscar tells us something about globalisation, sustainability and equality. These are the three key themes of this book because they are the key themes of geography in the 21st century, and our concern here is with exploring what the study of geography means today and what it could mean for the future. The academic subject of geography has existed for many years, but the themes of globalisation, sustainability and equality have not always been of such paramount interest to those who pursued the study of geography in the past.

Next page