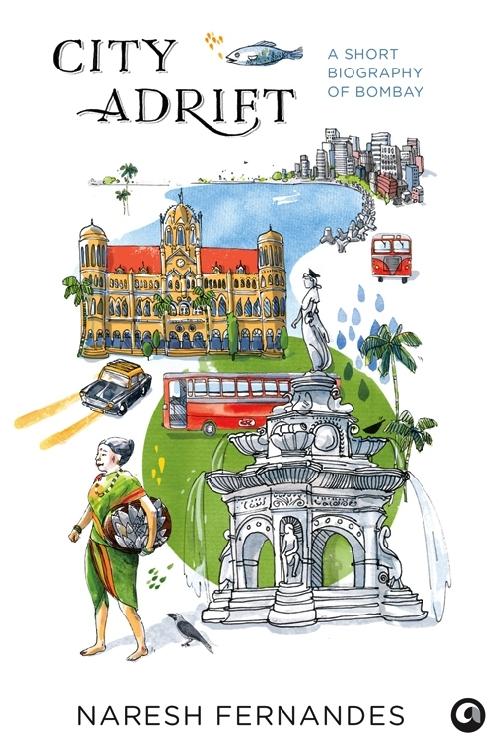

About the Book

For hundreds of years Bombay held India in thrall. A metropolis, 'reclaimed from ocean and iniquity', it effortlessly manufactured the dreams that captivated a nation and drew fortune-seekers to it by the million. Once a princess's dowry, these seven conjoined islands were settled over time by the most diverse collection of people the Indian subcontinent has ever known; they proceeded to create a mishmash culture that perfectly reflected their heterogeneity and gave the city its unique verve. No longer. For some time now, Bombay's charms have been wearing thin, other cities have become more alluring, and disastrous new trends such as its 're-islanding' into luxury ghettos, could spell its final descent into chaos and terminal decay. In this arresting new biography, award-winning writer and journalist, Naresh Fernandes, writes with a mixture of passion, exasperation, poignancy, empathy and great elegance about his beloved Bombaygiving us a very deep understanding and appreciation of one of the world's most iconic cities.

About the Author

Naresh Fernandes is the editor of Scroll.in, a digital newspaper. He is the author of Taj Mahal Foxtrot: The Story of Bombay's Jazz Age , which won the Dr. Ashok Ranade Memorial Award and the Shakti Bhatt First Book Prize. Fernandes is a Poesis fellow at New York University's Institute of Public Knowledge.

ALEPH BOOK COMPANY

An independent publishing firm

promoted by Rupa Publications India

This digital edition published in 2013

First published in India in 2013 by

Aleph Book Company

7/16 Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110 002

Copyright Naresh Fernandes 2013

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic, mechanical, print reproduction, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Aleph Book Company. Any unauthorized distribution of this e-book may be considered a direct infringement of copyright and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

e-ISBN: 978-93-83064-39-7

All rights reserved.

This e-book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publisher's prior consent, in any form or cover other than that in which it is published.

Also by Naresh Fernandes

Taj Mahal Foxtrot: The Story of Bombays Jazz Age (2012)

PART ONE

ONE

For months, the front pages had warned of imminent doom. Bombay was reeling under an explosion of pollution, crowds and noise, noted one pessimist. Predicted another, The urban landscape of Mumbai with its ever-increasing vehicular and population growth is a nightmare for everybody. And the nightmare will only worsen every year.

Such a barrage of despair would have spooked the residents of most cities, but these forecasts were especially unnerving because they were contained in full-page advertisements aimed at getting people to pay outrageous amounts of money to actually live in Bombay. Every day, in The Times of India and DNA , in Mid-Day and the Hindustan Times, the real estate firms constructing Bombays present were proclaiming with disarming candour that they had no faith in its future. But even as they expressed exasperation with the problems that were besetting contemporary Bombay, the developers proposed a simple solution: complete retreat.

They were encouraging residents to sequester themselves in housing complexes with names like Vasant Oasis (reside at newer heights of happiness), Rodas Enclave (where a refreshing lifestyle flourishes) and Marathon NexZone (next-generation eco-friendly Xtra utility homes).

Some of the housing complexes offered as sanctuaries bore names suggesting that theyd seceded from Bombay altogether. Kohinoor City in Kurla was in a class of its own. Sports City in Thane was a mini metropolis that offers its residents world-class sporting facilities. Rising City in Ghatkopar was the answer to Mumbais need for space in a green environment.

Amidst these expensive propositions for alternative cities, the pitch made for one complex in Wadala caught my eye for the artful manner in which it had appropriated one of the citys most resonant foundational myths. The headline of one of its advertisements gloated: The eighth island of Mumbai discriminates. I needed to know more.

As every schoolchild is taught, a large portion of contemporary Bombay has been conjured up over the centuries by reclaiming the tidal creeks separating the seven apocryphal islands that the Greeks are believed to have known as Heptanesia. This conjoined land was settled by the most diverse collection of people the subcontinent had ever known, who proceeded to create a mishmash culture that perfectly reflected their heterogeneity and verve.

This aspect of Bombay life can best be understood by eavesdropping on the conversations surging through its streets. When Bombayites pick arguments with, make purchases from or proposition strangers with whom they share no common tongue, they do so in an argot that amalgamates the syntax and vocabulary of half a dozen linguistic traditions. It wraps Hindi, Urdu, Gujarati, Marathi and English into the embrace of a dialect Salman Rushdie named Hug-me. Bombays aptitude for aggregation can also be tasted in the snacks sold on its footpaths: Chinese bhel, Schezwan idlis and cheese dosas are made with ingredients (blended together with a large dollop of enterprise) that share the skillet only in this city. Even though these ensembles seem ungainly to some, Bombay has, over the last two hundred years, held India in thrall. For, in addition to inventing snacks and slang, the proud denizens of the metropolis reclaimed from ocean and iniquity have specialized in producing a commodity that is rather more incandescent. The city of interlocked islands, its widely acknowledged, is the place that manufactures Indias dreams.

The idea of India was born in Bombay in 1885, when the Indian National Congress held its first meeting in Gowalia Tank. The notion that workers deserved a fair deal followed in 1890, when the first Indian trade union was formed in the mill district. For a century, the Bombay film industry has been projecting visions of egalitarianism and meritocracy and love marriages into the heartland, suggesting that any adversity can be overcome if you work hard enough (and dance around a tree in the appropriate fashion). To be fair, not all Bombay fabrications have been salutary: since the 1990s, the citys financial institutions and advertising agencies have seduced Indias middle class into believing that greed is good, that empathy for the less fortunate is unnecessary, that extreme individualism is a virtue.

But that stream of dreams was running dry, or so said the property developer in Wadala. Bombays ability to keep generating Indias fantasies would be imperilled unless the citys geography was completely reconfigured. Luckily, help was at hand. Keeping the meteoric growth of the city in mind, the firm claimed to have constructed not just an eighth island but one that dwarfs the other seven.

The twenty-nine-acre Island City Centre would be an exclusive integrated enclave of branded residences and serviced apartments, of business centres and shopping malls, that even had the capacity to expand time at will. Freed from the morass of a traffic-snarled city, residents could pack a weekend into every weekday. They would get private roads, temperature-controlled lobbies and separate service lifts to ensure that the service staff remains largely invisible. Could I too discover a better life, as the copywriter had urged?