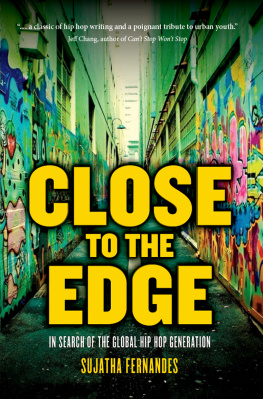

CLOSE TO THE EDGE

CLOSE TO

THE EDGE

In Search of the Global

Hip Hop Generation

Sujatha Fernandes

First published by Verso 2011

Sujatha Fernandes 2011

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

eISBN: 978-1-84467-827-3

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Minion Pro by MJ Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Vail

For Mike Walsh

Contents

Preface

Don't push me cause I'm close to the edge

I'm trying not to lose my head

It's like a jungle sometimes, it makes me wonder

How I keep from going under.

Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, The Message

L ate one Friday night in my teenage years, I was watching the Australian music video show rage, and I saw a flashback video of the 1982 rap hit The Message. I was growing up in Maroubraa working-class beachside neighborhood of Sydney that was bordered by a jail, a sewage treatment plant, and the project-like Coral Sea Housing Commissions. I was captivated by the raw and angry lyrics that laid bare ghetto realities in Reagan's America. Back then I didn't know the story behind the songthat, although it was credited to the legendary Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, it was mostly written and recorded by a session musician not even in the band, and the band members who appeared in the video were lip-synching to the song. But there was something fitting about my close identification with a fabricated product that revealed so many truths. Any imagined connection I felt to an American ghetto was contrived at best, yetand I don't know whythe song struck a chord with me.

My interest in hip hop had begun with lessons in b-boying at a workshop run by the Randwick Municipal Council. After we saw Michael Jackson's video clip Thriller, all the kids at my school wanted to do the moonwalk. But, unlike the b-boys and b-girls in the Bronx, who developed the dance styles at house parties, outdoor jams, and school hallways, we were taught the moves by our local city authorities. I was mesmerized by the scratching and raw energy of rapping in Run-DMC's Walk This Way on Countdown, a music show presented by an Egyptologist in a cowboy hat named Molly.

Salt, Pepa, DJ Spinderella, and Neneh Cherry were my role models and my guide to male-female relationships through the angst of adolescence. They created images of black beauty and sexuality that had not been available to us in Australia. When they talked back to menDon't you get fresh with me, and Yeah, you, come here, gimme a kissthey inverted the game of male pursuit that we had come to see as the norm. My friends and I would go to the downtown clubs like Kinselas to dance and hear the latest music. We used the music to escape the small and parochial world of our classmatesof Saturday night drinking binges and casual hookups at local working-class pubs known as Returned Servicemen's Leagues (RSLs).

My growing fascination with rap music paralleled my political awakening. At college in the early 1990s, I joined a youth organization, Resistance, and became a full-time activist. At the time I was spending hours in the secondhand music stores along Pitt Street downtown, discovering records from Boogie Down Productions, Digable Planets, Public Enemy, and A Tribe Called Quest. My cousin Miguel Dsouza had the first hip hop radio show in Sydney, where I heard political rap from the States. The godfathers of rap, The Last Poets, had prophesized that the revolution was coming. It seemed that, with the intifada in Palestine, the Fretilin guerrillas in Indonesia-occupied East Timor, and rebellious youth facing down tanks in the streets of Jakarta and Durban, global revolt was imminent. So why didn't anyone on my block know it?

It finally dawned on me one day. I was with other, mostly white, activists, handing out leaflets at Sydney's town hall to protest the spate of deaths of Aboriginals while in police custody. But all the Aboriginal kids were walking right on past us. Just around the corner b-boys had laid out their cardboard strip and were doing head spins and windmills. I watched the crowdimmigrant, Aboriginal, and white kidsthat was gathering around them. I realized then that hip hop culture was speaking to them in a way that we activists were notcould not.

It was this revelation that sparked my quest to find a global hip hop generation. Afrika Bambaataa had talked about a Universal Zulu Nation. KRS-One had rapped, In every single hood in the world I'm called Kris. Chuck D had described the collective consciousness of a black planet. Inspired by these spokespersons for a new era, I began what would become an eleven-year odyssey across four countries in search of what exactly it was that made hip hop such a powerful global force.

But before I take readers on this journey, I want to rewind a little, to think about how hip hop went global in the first place.

INTRODUCTION

The Making of a

Hip Hop Globe

P edro Alberto Martnez Conde, otherwise known as Perucho Conde, was probably the first rapper to compose a hit song outside the United States. A poet and comedian from the inner-city Caracas barrio of San Agustn, Conde was perplexed by the strange but catchy lyrics of the Sugar Hill Gang's 1979 hit Rapper's Delight. In 1980 he came up with a Spanish version that went to the top of the charts in Latin America and Spain.

Far from the outdoor jams and battles of the Bronx scene where hip hop originated, Rapper's Delight was packaged and designed for travel. But that didn't mean global audiences got it. Conde baptized his imitation La Cotorra, the term for a pompous and long-winded speech. Other take-offs surfaced from Jamaica to Brazil; in Germany the song was called Rapper's Deutsch. Cubans called it Apenej, because nobody could make sense of the lyrics. As the first rap song to go global, Rapper's Delight embodied the mix of fascination and incomprehension that would accompany the spread of early rap.

By the early 1980s the global circulation of hip hop through the music industry was being paralleled by the efforts of hip hop ambassadors like Afrika Bambaataa to spread a message of black brotherhood and unity. Back in 1973 Bambaataa had founded the Universal Zulu Nation, a Bronx-based street organization that drew on the mythology of anticolonial South African warriors to redirect the energies of inner-city gang youth. In April 1982 Bambaataa released his single Planet Rock, an anthem for this nascent movement, which was producing chapters across the city. With its mix of European technorock, funk, and rapping, Planet Rock was a model of fusion that imagined unity across cultures the same way Bambaataa had created unity across gang lines.

As he toured Europe and England in November, Bambaataa hoped to set the groundwork for the global spread of his movement. North African immigrant youth in the