From the international reviews of Holy Warriors

This is an amazing book, incredible. Anyone interested in religions and how they get on or dont should get hold of it. Im telling you, its a compulsive read Nihal, BBC Asian Network

Deploying her skills as a reporter, Fernandes offers a very readable, at times funny but always very informative account of her travels and meetings with the fundies of all creeds. She does a good job of capturing the texture of radical religious outfits. What is especially valuable is how she picks up the thread of forgotten news stories. She tells a good tale. New Humanist

What a cast of characters make their way through this sharp-witted and straight-talking book: the fatuous and the venal, the self-important and the deluded, the exploitative and the corrupt. Edna Fernandes has undertaken to track down figures who epitomise the most depressing facet of Indian life its holy warriors as well as some of their victims. Her odyssey takes her far and wide from Nagaland and Kashmir in the north down via Punjab and on to Goa. It regularly deposits her in daunting situations. A number of clear observations emerge from its mosaic of research and reportage The reportage is even-handed and responsible and even delightfully witty. Fernandess asides are precise and wicked. Above all, she offers a valuable reminder of the dark side of the economic miracle that is modern India. Naseem Khan, Guardian

This energetic account of religious violence and prejudice in India is witty, informative and disturbing. Purity and impurity, rather than good works and sin, would appear to constitute the dominant polarity in religious consciousness on the Subcontinent. But one faiths purity may be anothers filth Holy Warriors sets out to explore the conundrum: what exactly is the relationship between fanatical religious observance and sectarian violence in modern India? The book opens with a brief consideration of Partition, the carnage that accompanied it and the unhappy irony that it did not produce clear and separate national identities for Pakistan and India After the grim facts, Fernandes tells of her own trips to these troubled areas and her long interviews with the many of those involved in the violence: victims, police chiefs, religious leaders, politicians (but not the killers). Her travelogues are attractive; she is a witty caricaturist, and a stubborn interviewer often fun, always informative, Holy Warriors is a useful introduction to the sectarian divides of contemporary India. Tim Parks , Telegraph

Fernandes travels the country meeting ministers, activists and those caught in the crossfire to give an even-handed portrayal of a sensitive subject. Metro

An entertaining and insightful thematic travelogue, a tour of Indian flashpoints. Economist

Fernandes reports on Indias differences with compelling insight Holy Warriors makes for vital reading, showing Indias urgent need to rearticulate an inclusive identity, to master change and exceed past glories. Independent

A journey of discovery into some of the tensions that regularly stretch India. Literary Review

This is a remarkable, brave, moving, disturbing, funny and at times beautiful book. It tackles head-on the great Indian paradox, which most observers tend to ignore or obfuscate: that India is a centre of religion and spirituality, and hence of tolerance, celebrating the many paths available to those seeking the Godhead; yet it has also been home to some of the most terrible atrocities committed anywhere in the name of religion. Simon Long, Asia Editor, Economist

Holy Warriors

A Journey into the Heart of Indian Fundamentalism

EDNA FERNANDES

Table of Contents

Preface

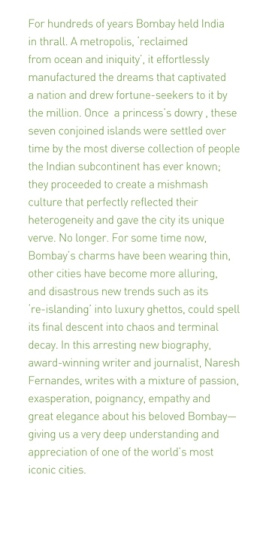

August 15, 1947 is a date etched upon the soul of every Indian. It is the day India won its freedom from the British Empire. Yet it is also the date of Partition, an act which carved up India along religious lines to create the Islamic state of Pakistan, igniting violence which killed more than a million people. 2007 sees the 60 th anniversary of these events, unifying the jubilation of Independence with the grief of a nations division.

The horror of Partition lives on in the psyche of the Indian people to this day, a dark reminder of how the country was forced to pass through the communal fires in order to be reborn as a new nation. Partition has until now remained the defining act in Indias post-Independence history: establishing the basis for relations with Pakistan as well as relations between Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs within India. In the days that followed August 15, 1947, India witnessed a kind of collective madness that saw its communities poisoned by the politics of the religious fanatic.

The seeds of this book were sown by reading reportage and fictionalized accounts of the events of 1947. I remember being particularly struck by a slim volume of short stories by Saadat Hasan Manto called Kingdoms End , in which the small lives of ordinary men were used to reflect the great issue of the time: Partition and how religion had come to define a persons identity.

These brief, sparely written tales of how communal division destroyed lives across religious boundaries drew me into a subject which resonates in India to this day. Manto was a Muslim Kashmiri who grew up in Punjab and moved to Bombay. Yet he did not write as a Muslim, or indeed as a Kashmiri, nor even an Indian. Instead, his was the humane voice of detached reason that chronicled the societal breakdown that followed Indias division.

The most moving story of all is that of Toba Tek Singh, a man from an asylum who cannot comprehend the dismemberment of his country and so flees to a no-mans-land between India and Pakistan, where he stands in protest until collapsing into the dust with grief: There, behind barbed wire, on one side lay India and behind more barbed wire, on the other side lay Pakistan. In between, on a bit of earth which had no name, lay Toba Tek Singh.

Sixty years after Partition, India and the post-9/11 world at large remain fixated by the dangers of religious division and fundamentalism. While the Western world is newly alert to the threat posed by extreme Islam, India as the worlds largest secular democracy has decades of experience of how every strand of religion can be hijacked by the politics of the fanatic and the lessons of Indias battles against holy warriors from Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism and even Christianity are more relevant than ever today on a global scale. The de-humanizing effect on the Toba Tek Singhs of this world is now evident, from London to New York, and from Baghdad to Jerusalem. The anniversary of Partition seemed an opportune moment to revisit the issue in India, to discover how the religious divisions in the country have shaped the political and cultural landscape over the last sixty years, and to try to understand what turns a believer into a holy warrior.

Since Holy Warriors was first published in India in 2006, there have been a few developments, some positive, some less so. The Congress-led national government has persisted with its policy of seeking to rehabilitate religious minorities back into the Indian family through economic engagement and dialogue in a bid to quell religious unrest. It has continued to pursue peace talks with Pakistan, exploring growing trade, travel and intellectual links as steps towards normalized relations.

That policy has yielded results, with Pakistan hinting that it may consider giving up its longstanding claim to Indian-held Kashmir in return for certain concessions; a sign that realpolitik may yet prevail over dogma, as both sides recognize that economic re-generation of the region has become the real issue of the day.