Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this ebook to you for your personal use only. You may not make this ebook publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this ebook you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In memoriam Rosemary Stark

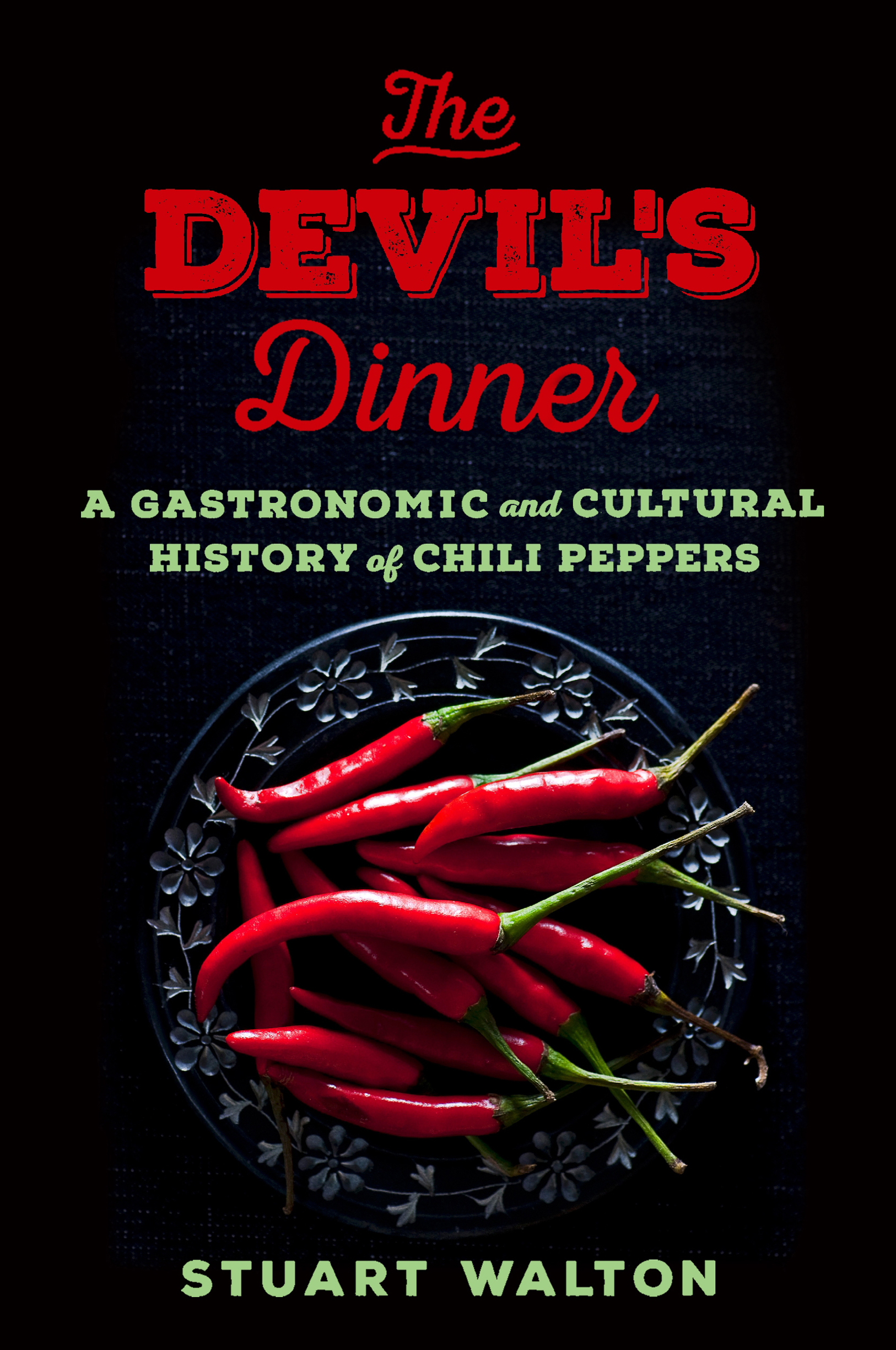

At the time of this writing, Smokin Eds Carolina Reaper, grown by the PuckerButt Pepper Company in South Carolina, is officially the worlds hottest pepper . On the Scoville heat unit (SHU) scale used throughout most of the last hundred years to measure the hotness of chilies (and which measures the McIlhenny Companys Tabasco sauce at somewhere in the range of 2,5005,000 SHU), tests at Winthrop University have calibrated the Reaper at 1,569,300 SHU. In other words, you would have to dilute the ground pepper in sugar solution more than 1.5 million times before you could no longer detect its heat. And if you dont dilute it at all, you may well detect its heat 1.5 million lifetimes after introducing it to your tongue.

The cute little Carolina Reaper is emergency-room red, with a delicate, wrinkly body tapering to a little point like a hornet stinger. Its squarish shape is not unlike that of a miniature bell pepper, but there the resemblance ends. Swallowing one Reaper can set your whole soul on fire; the SHU reading of a bell pepper is zero. When bell peppers began appearing in groceries in northern Europe in the 1960s, many consumers were convinced that they would be hot and spicy, a misapprehension that obstinately outlasted the first taste for many who dared to try them. They were red peppers, and red pepper was what went into hot sauces like Tabasco, or what turned up in little jars labeled cayenne, for deviling up your eggs or adding a warmish luster to your first attempts at goulash.

Whole chili peppers were only available in these formative times from Asian and West Indian groceries, into which only their respective Chinese, Indian, and Caribbean constituencies ventured. Now chilies are on most supermarket shelves. Everybody knows that you cant cook Mexican or Thai or Indian food without them, although people still cling to certain potently persistent chili myths, such as that the smallest ones are hottest, the red ones are the hottest, or that all the hotness is contained in the seeds.

In contrast to these early, nervous encounters, an enthusiastic hot pepper movement has sprung up in the modern era, extending deep roots not just into the southern United States but across the length and width of the nation, spawning festivals and academic colloquia and broadening the range of hot sauce products available everywhere from specialist delicatessens to menus at fast-food franchises. In the United Kingdom, too, a hot sauce movement has coalesced around a perennial calendar of fiery-food festivals, hives of devotional activities that often include a chili-eating contest, over which a small coterie of intrepid maniacs exercises the same dominance as does an exclusive band of elite players over the international tennis circuit.

Chili, which was once terrifying to the Anglo-American imagination, is now big businessand big culture, too. The pepper has generated its own study institute at New Mexico State University, responsible in 2006 for identifying what was then the worlds hottest pepper, the bhut jolokia, a hybrid variety of Eastern India that is about two-thirds the strength of PuckerButts finest. Annual conferences and research programs for plant breeding supplement the institutes dedicated work of situating hot peppers in the cultural and gastronomic imaginary of chefs and consumers, a labor of assimilation that has turned the one blaring signal that chili peppers developed at the origin of their evolutiona warning to mammals to stay well away from theminto just what is most attractive about them.

Hot pepper culture is a triumph of alimentary defiance over biological instinct. Like many a potent intoxicant, the chili promises immediate sensual pleasure as well as an aftermath of pain, and a rather instant aftermath at that. There are ecstasies of regret to be had from tasting even a tiny fragment of chopped hot pepper, and infernal miseries for those who, soon after the chopping, carelessly rub their eyes, put in their iPod earbuds, or visit the bathroom. (Among the suggestions an online forum offered to sufferers in that last category were to apply yogurt to the affected organ, ormore enterprisingly, if less effectivelyto run outside and expose it to the air.) Yet none of this is sufficient to deter hardcore chili aficionados. Rather, pain only encourages them.

Chili has undergone a transition from a foodwhether a simple spice, an ingredient, or the emblematic dish known across the Western world as chili con carneto a way of life, the structuring principle of encounters with food that have long left behind the idea of simple sustenance or nourishment and turned into a transformative experience. In cultures ambivalently torn between individual liberty and social subversion in the matter of controlled substances, the hot pepper movement has become gastronomys own version of a drug subculture. Nothing involved in the movement is illegal, as long as whats involved are the peppers themselves and not their pure alkaloid capsaicin, which was banned as a food additive in the European Union in January 2011 on the grounds that an extremely high intake of it could be carcinogenic. But the culture surrounding chilies is one of willingly incurred risk to ones soft tissue and overall gastric harmony, while the race to produce ever more concentrated, searing heat in each new variety reflects the trend toward increasing intensity in the synthetic compounds targeted at users of street drugs. Some scientific researchers even claim that a taste for chilies is in itself a species of addiction, with its own cognate pattern of initial rejection followed by the gradual development of tolerance and then the eventual craving for more of the stuff in hotter versions once the old ones no longer cut it.

Much of this would doubtless bemuse those cultures where the raging fire of chili has been gastronomically indispensable for centuries. A Thai banquet that opens with a bowl of tom yum soup locks the taste buds in an immediate wrestling hold from which it mercilessly wont relinquish them: the salty pungency of nam pla (fish sauce) and the unapologetic sour sting of lime juice, lemongrass, and tomato are undergirded by roaring waves of white-hot fury from a fistful of finely minced red chili. What subsequent dishes can the tenderized palate possibly register in the aftermath of such an assault? Only ones sizzling with more chili.

In the tiny Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan, sometimes known as the worlds last Shangri-la, chilies are no mere spice ingredient, but are pure sustenance in themselves, eaten as the principal item in curry dishes that might include supporting bulk from soft cheese (as in the national dish, ema datshi ), and as the condimentchili picklethat adds relish to a whole repast. Chilies came to Bhutan via India, probably in the eighteenth century, and were adopted more wholeheartedly there than anywhere else on earth, such that a standard purchase of a kilo (2.2 pounds) of whole peppers, the local variety known as sha ema, is the minimum weekly requirement for a small family.