Contents

Guide

SCIENCE

HACKS

HACKS

100 clever ways to help you understand

and remember the most important theories

COLIN BARRAS

Contents

How to Use This Ebook

Select one of the chapters from the and you will be taken straight to that chapter.

Look out for linked text (which is in blue) throughout the ebook that you can select to help you navigate between related sections.

You can double tap images and tables to increase their size. To return to the original view, just tap the cross in the top left-hand corner of the screen.

Introduction

For some students in North America, the first geology lesson is about poker. For others, it focuses on pearls. My British geology teacher opted to talk about camels. In all three cases, the idea is to make sure the students learn the main geological divisions of the last half a billion years or so Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, and so on. The details vary, but the method of choice is the same: a mnemonic.

Come over some day, maybe play poker. Three jacks can take queens.

Cold oysters seldom develop many precious pearls, their juices congeal too quickly.

In the UK, where the geological divisions chosen are slightly different, the mnemonics run something like this: Camels often sit down carefully. Perhaps their joints creak? Early oiling might prevent permanent rheumatism.

Science is packed full of these phrases. There are mnemonics for remembering the order of the planets of the Solar System, the chemical elements of the periodic table and the different taxonomic ranks used to classify organisms. But these are not the only little hacks scientists and science students can use to memorize key bits of information. One of the most effective ways to remember a scientific theory or law is to boil it down to a pithy phrase.

Within a few years of the publication in 1859 of On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwins theory of evolution by natural selection had been reduced to a simple expression: survival of the fittest.

Another of the great mid-19th century scientific achievements was the formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics. Today, many physicists and non-physicists alike sum them both up in one memorable witticism: you cannot win, and you cannot break even.

Reduce a core scientific concept too far, though, and you can run into trouble. Some people dismiss survival of the fittest as a tautology (they argue it could be rewritten as survival of those that survive). The single sentence summary of the first and second laws of thermodynamics, meanwhile, is rather cryptic to anyone who does not already know what the two laws are. In this book, I have aimed for a middle ground. The hacks that follow may not be as clever or instantly memorable as the famous examples above, but I hope they are a little more useful especially for those who want to find a shortcut to understanding some of the most challenging concepts in science.

No.1

The theory of evolution by natural selection

Why Darwin matters

Charles Darwin // 18091882

1/Helicopter view: Most people have heard of Charles Darwin. In the 1830s, Darwin traveled to exotic lands on the Royal Navy ship HMS Beagle. Among many observations he made, Darwin noticed how much variability there is in the natural world, and the difficult struggle for existence individual organisms face.

1/Helicopter view: Most people have heard of Charles Darwin. In the 1830s, Darwin traveled to exotic lands on the Royal Navy ship HMS Beagle. Among many observations he made, Darwin noticed how much variability there is in the natural world, and the difficult struggle for existence individual organisms face.

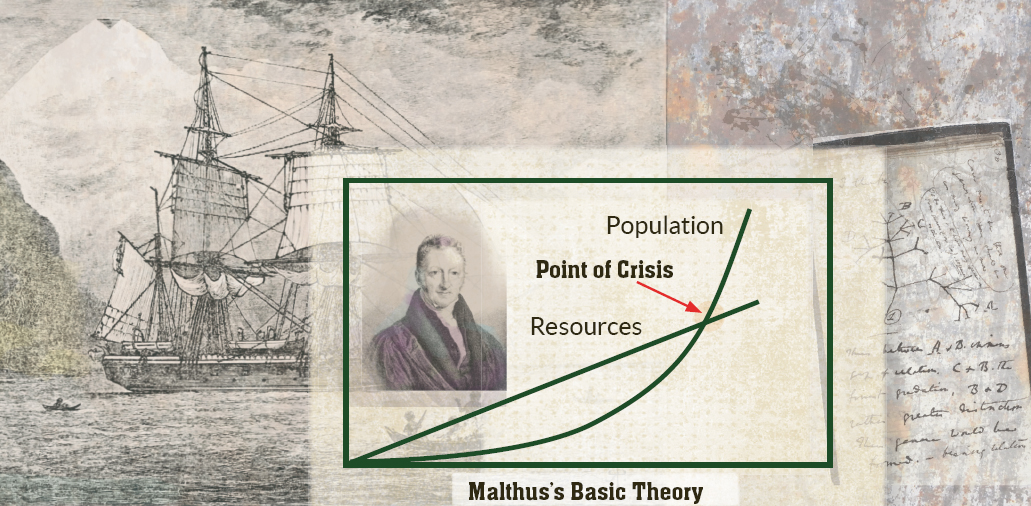

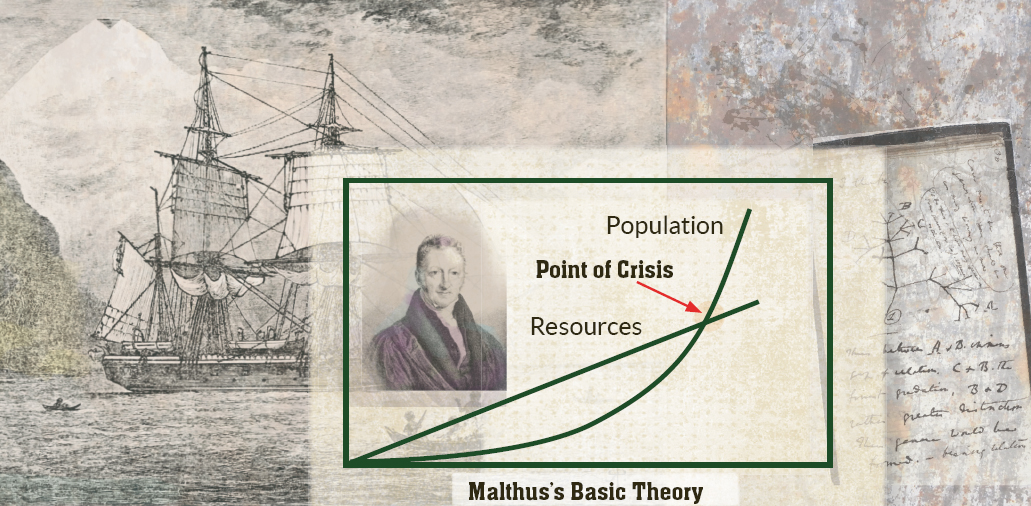

A couple of years after his return to England, Darwin read an essay by economist Thomas Malthus, which painted a bleak picture of humanitys future: populations could double with every passing generation, but food production would fail to keep pace, leading to starvation for many another struggle to survive.

Darwin suspected that a Malthusian-like struggle plays out in the natural world, and that this struggle could form the basis of a mechanism through which new species evolve.

Perhaps surprisingly, Darwin didnt rush to publish. He shared his ideas with friends, who suggested the argument could be made stronger with a larger body of supporting evidence. Darwin took the advice, and spent several years studying species to gather such evidence.

Then, in the 1850s, he received word from another scientist working in Indonesia. Independently, Alfred Russel Wallace was homing in on a very similar view of the evolutionary process. In 1858, a scientific society in London heard letters from both Darwin and Wallace explaining the new idea. The following year, Darwin published a lengthy book setting out his evidence for evolution by natural selection. On the Origin of Species became famous. Darwins reputation was sealed.

Darwin was influenced by his voyage on the Beagle and reading Malthuss work.

2/Shortcut: Darwin realized that organisms often give birth to large numbers of offspring. There is variability among those offspring: some might have slightly longer limbs or sharper eyes, for instance. Most individuals will struggle to survive, but a lucky few will have features that make it easier for them to flourish, so they will prosper and breed they will be naturally selected. Darwin assumed these individuals offspring would inherit some of the beneficial features, and so over time these features would become more common in the population. Gradually, the population will evolve into a new species characterized by the new features.

2/Shortcut: Darwin realized that organisms often give birth to large numbers of offspring. There is variability among those offspring: some might have slightly longer limbs or sharper eyes, for instance. Most individuals will struggle to survive, but a lucky few will have features that make it easier for them to flourish, so they will prosper and breed they will be naturally selected. Darwin assumed these individuals offspring would inherit some of the beneficial features, and so over time these features would become more common in the population. Gradually, the population will evolve into a new species characterized by the new features.

3/Hack: Some individuals are just inherently better suited to their environment than others. They are more likely to survive and breed.

3/Hack: Some individuals are just inherently better suited to their environment than others. They are more likely to survive and breed.

Consequently, they have more influence on the evolutionary trajectory of their lineage.

See also //

No.2

The principle of coevolution

Darwins astonishing predictive powers

Gaston de Saporta // 18231895

1/Helicopter view: In the years following the publication of

1/Helicopter view: In the years following the publication of

HACKS

HACKS

1/Helicopter view: Most people have heard of Charles Darwin. In the 1830s, Darwin traveled to exotic lands on the Royal Navy ship HMS Beagle. Among many observations he made, Darwin noticed how much variability there is in the natural world, and the difficult struggle for existence individual organisms face.

1/Helicopter view: Most people have heard of Charles Darwin. In the 1830s, Darwin traveled to exotic lands on the Royal Navy ship HMS Beagle. Among many observations he made, Darwin noticed how much variability there is in the natural world, and the difficult struggle for existence individual organisms face.

2/Shortcut: Darwin realized that organisms often give birth to large numbers of offspring. There is variability among those offspring: some might have slightly longer limbs or sharper eyes, for instance. Most individuals will struggle to survive, but a lucky few will have features that make it easier for them to flourish, so they will prosper and breed they will be naturally selected. Darwin assumed these individuals offspring would inherit some of the beneficial features, and so over time these features would become more common in the population. Gradually, the population will evolve into a new species characterized by the new features.

2/Shortcut: Darwin realized that organisms often give birth to large numbers of offspring. There is variability among those offspring: some might have slightly longer limbs or sharper eyes, for instance. Most individuals will struggle to survive, but a lucky few will have features that make it easier for them to flourish, so they will prosper and breed they will be naturally selected. Darwin assumed these individuals offspring would inherit some of the beneficial features, and so over time these features would become more common in the population. Gradually, the population will evolve into a new species characterized by the new features. 3/Hack: Some individuals are just inherently better suited to their environment than others. They are more likely to survive and breed.

3/Hack: Some individuals are just inherently better suited to their environment than others. They are more likely to survive and breed.