Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

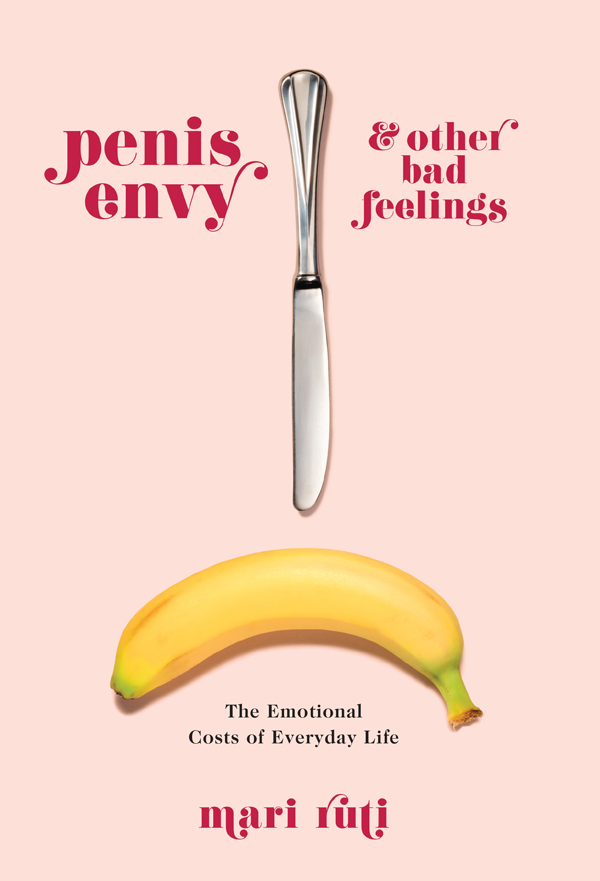

PENIS ENVY AND OTHER BAD FEELINGS

PENIS ENVY AND OTHER BAD FEELINGS

THE EMOTIONAL COSTS OF EVERYDAY LIFE

MARI RUTI

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54676-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ruti, Mari, author.

Title: Penis envy and other bad feelings : the emotional costs of everyday life / Mari Ruti.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017049985 | ISBN 9780231186681 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Critical theory. | Negativity (Philosophy) | EmotionsSocial aspects. | Neoliberalism. | Feminist theory.

Classification: LCC HM480 .R88 2018 | DDC 128/.37dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017049985

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design by Julia Kushnirsky

Cover photo by Geoff Spear

This book is dedicated to those who threw the lifeline:

Sean Carroll

Doreen Drury

Jess Gauchel

Steph Gauchel

Alice Jardine

Marjorie McClung

Jean Russo

Josh Viertel

CONTENTS

F or a long time, Sigmund Freud has been accused of being a misogynist because he claimed that women suffer from penis envy. I remember that when I first came across this idea in college, I threw Freuds book across my dorm room and declared him a fucking idiot. I dont blame anyone for having the same reaction: surely theres something outrageous about claiming that when a little girl sees her brothers penis, she instantly starts to covet it because she recognizes her own inferiority.

But after studying feminist theory and related fields for three decades, Ive come to see that its possible to spin Freuds claim differently: in a society that rewards the possessor of the penis with obvious political, economic, and cultural benefits, women would have to be a little obtuse not to envy it; they would have to be a little obtuse not to want the social advantages that automatically accrue to the possessor of the penis, particularly if he happens to be white.

Because Freud (who was otherwise a pioneering thinker) wasnt always able to transcend the blatant sexism of his nineteenth-century cultural context, his wording at times implies that its the penis itselfrather than the social privilege it signifiesthats the object of envy. Nevertheless, its possible to read his argument about penis envy as an indication that women in his Viennese culture, who didnt have many public outlets for their frustration or rage, were aware that femaleness carries less social currency than maleness. In other words, what many have taken as a mortifying insult to womenFreuds notion of penis envycan be reinterpreted as an embryonic sign of female dissatisfaction; it can be reinterpreted as a precursor to feminist political consciousness.

Given the historically subservient status of women in Western societiesas in most other societieswe might wonder less about the existence of penis envy than about why its not more pronounced. To this day, our society implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) codes the possessor of the penis (the man) as having something while coding the one who doesnt have a penis (the woman) as lacking something. This in turn suggests that a man is an active subject whereas a womanthe one who lacksis a passive object: a nonsubject who requires completion by the subject (the man). Why, then, arent women screaming bloody hell? Why isnt every woman an ardent feminist?

Later in this book Ill examine some reasons for this state of affairs, including the possibility that women have been taught to eroticizeand therefore find pleasure intheir subordination. But first I want to assure my male readers that this book is aimed at them as much as its aimed at women. In part this is because it touches on other bad feelings besides penis envy, such as depression and anxiety. But in part its because I believe that many men suffer from penis envy just as much as women do.

This claim is less counterintuitive than it may at first appear, for if the penis functions as a socially valorized emblem of phallicheteropatriarchalauthority, then even those who possess the organ may feel like they arent able to exercise its authority; they may feel like theres a discrepancy between this icon of robust confidence and the insecure realities of their lives. In this sense, if the cultural mythology surrounding the penis can make women feel deficient, it can make men feel like frauds.

But if phallic authority is a mere fantasy-infused cultural mythology, why would anyone be stupid enough to feel bad about not having it? In response to this question, I want to suggest that the mythological status of the phallus may actually increase its appeal. After all, many people routinely desire things that they imagine others to have, such as the good life, happiness, peace of mind, perfect relationships, mansions with no heating problems, and so on. That these things may not in reality existthat the lives of those who are envied may in reality be less enjoyable than they appear from the outsidein no way prevents them from being objects of envy. In the same manner, phallic power doesnt need to be empirically real to function as an object of envy; the fact that the (masculine) social prestige of the phallus is illusorymore on this topic shortlydoesnt change the reality that we still live in a heteropatriarchal society that conditions us to want this prestige.

The penis as a signifier of phallic power is a collective fetish, a magical totem pole thats meant to protect us from danger, including any and all enemies of the state. This is why the pissing contest between the American government and its opponents is unlikely to end any time soon. Yet this contest also highlights the purely fantasmatic nature of phallic authority that Ive just called attention to because it reveals that this authority frequently cant deliver what it promises: no matter how many missiles the government accumulates, it cant keep the other guy from pissing in its backyard (or hacking into its computer systems).

This is also the personal predicament of those menby no means all menwho make the mistake of thinking that their penises automatically make them powerful: there will always be times when their power falters, when theyre forced to reckon with the inherent fragility, precarity, and vulnerability of human life. This is why those of us who recognize the imaginary nature of phallic authority mock their red convertibles, flashy belt buckles, enormous cowboy hats, ostentatious hairdos, gilded high-rise residences, bombastic gestures, and exaggerated finger jabbing; we know that theyre caught up in a delusion of power, that their posturing hides a shakier reality.

In stressing the imaginary (mythological, fantasmatic, illusory) foundations of heteropatriarchy, I dont mean to suggest that its impact on women isnt real. Much of the time, it feels all too real, whether one is walking down the street, working in an office, or trying to have a romantic relationship. This is why this book has more to say about the persistence of heteropatriarchy than is considered polite in our (allegedly) postfeminist world, a world that has supposedly reached gender equality.