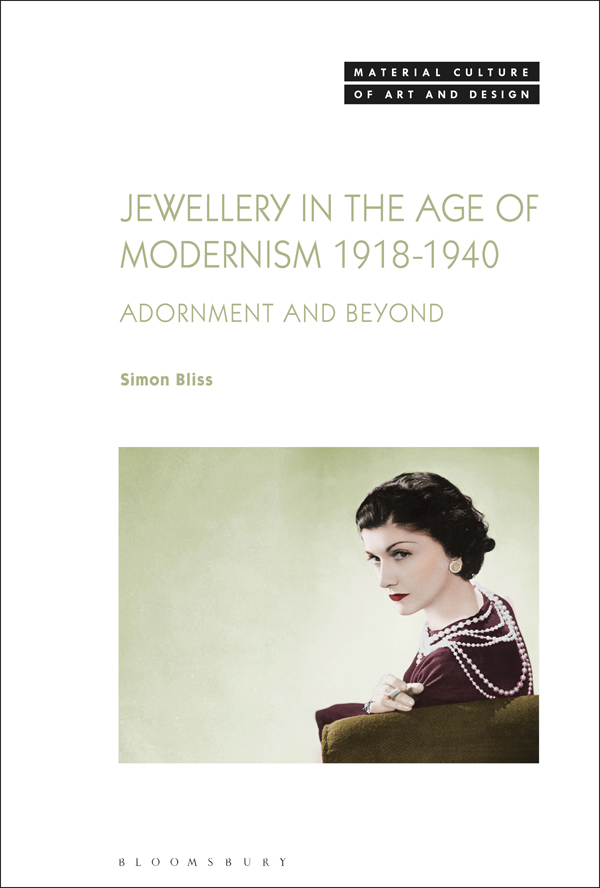

Jewellery in the Age of Modernism 19181940

To Cath, Tim and Ollie

Material Culture of Art and Design

Material Culture of Art and Design is devoted to scholarship that brings art history into dialogue with interdisciplinary material culture studies. The material components of an object its medium and physicality are key to understanding its cultural significance. Material culture has stretched the boundaries of art history and emphasized new points of contact with other disciplines, including anthropology, archaeology, consumer and mass culture studies, the literary movement called Thing Theory and materialist philosophy. Material Culture of Art and Design seeks to publish studies that explore the relationship between art and material culture in all of its complexity. The series is a venue for scholars to explore specific object histories (or object biographies, as the term has developed), studies of medium and the procedures for making works of art, and investigations of arts relationship to the broader material world that comprises society. It seeks to be the premiere venue for publishing scholarship about works of art as exemplifications of material culture.

The series encompasses material culture in its broadest dimensions, including the decorative arts (furniture, ceramics, metalwork, textiles), everyday objects of all kinds (toys, machines, musical instruments), and studies of the familiar high arts of painting and sculpture. The series welcomes proposals for monographs, thematic studies and edited collections.

Series Editor:

Michael Yonan

Advisory Board:

Wendy Bellion, University of Delaware, USA

Claire Jones, University of Birmingham, UK

Stephen McDowall, University of Edinburgh, UK

Amanda Phillips, University of Virginia, USA

John Potvin, Concordia University, Canada

Olaya Sanfuentes, Pontificia Universidad Catlica de Chile, Chile

Stacey Sloboda, University of Massachusetts Boston, USA

Kristel Smentek, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA

Robert Wellington, Australian National University, Australia

Volumes in the Series:

Childhood by Design: Toys and the Material Culture of Childhood, 1700Present edited by Megan Brandow-Faller

Domestic Space in Britain, 17501840: Materiality, Sociability and Emotion by Freya Gowrley

Domestic Space in France and Belgium: Art, Literature and Design (18501920) edited by Claire Moran

Georges Rouault and Material Imagining by Jennifer Johnson

Lead in Modern and Contemporary Art edited by Silvia Bottinelli and Sharon Hecker

Sculpture and the Decorative in Britain and Europe, Seventeenth Century to Contemporary edited by Imogen Hart and Claire Jones

The Art of Mary Linwood: Embroidery and Cultural Agency in Late Georgian Britain by Heidi A. Strobel

Contents

.

.

.

The idea for this book came from many years of teaching art and design history to students of architecture, interior design and jewellery practice. My first debt of gratitude is to those students of the latter subject area who were sufficiently enthusiastic about their studies to have found the act of researching and writing about jewellery (almost) as exciting and interesting as making it. My intention was (and still is) to try and promote the exploration of connections between jewellery and cultural circumstances in an effort to further uncover what such objects might mean. In doing this I have always tried to cast my cultural net as wide as possible, and so I thank all those who have been patient enough to sit through and engage with various versions of the material presented in this book.

My research has been greatly assisted by the librarians at The British Library, The National Art Library, and Goldsmiths Hall, London; The Bibliothque des Arts Dcoratifs and the Cinmathque Franaise, Paris; St. Peters Library, University of Brighton; The Wolfson Library, University of Oxford and the Bauhaus-archiv, Berlin. In addition, a number of museums, archives and galleries have been especially helpful in the task of locating and supplying images. In particular, I would like to mention the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas; the Archives Charlotte Perriand, Paris; the Schmuckmuseum, Pforzheim; the Muse de lAvallonnais, Avallon; the Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Kln; the President and Fellows of Harvard College, Cambridge, MA; The Bauhaus-archiv, Berlin; the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, DC; the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford; The Cole Porter Trust; the Galleria Martini e Ronchetti, Genoa; the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; The Irving S. Gilmore Music Library and the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

For personally granting me permission to reproduce photographs, I am very grateful to the following individuals: Claude Latour of The Fondation Alfred Latour, Robert Bell of The Literary Estate of Nancy Cunard, Lauren Cronley of Optoplast (Pollards International), John Benjamin and Sadie Murdoch.

I would also like to thank Laure Haberschill of the Bibliothque des Arts Dcoratifs for her help with locating books and photographs; Clare Phillips of the Victoria and Albert Museum for her assistance with the Eyston brooch; Klaus Weber of the Bauhaus-archiv for allowing me to examine Marianne Brandts costume for the Metal Party at first hand; and Sophia Tobin for assisting me at Goldsmiths Hall.

Finally, special thanks go to Lara Rettondini for her encouragement and linguistic assistance and, at Bloomsbury, to Margaret Michniewicz who helped me so much in the early stages of this project. I am grateful, too, for the support of colleagues at the University of Brighton and for allowing me some of the time, space and funding required to complete this book.

I hope I have managed to produce something that reflects well on the talents of all those who were kind enough to help me along the way. Needless to say, any errors of fact, interpretation or translation are entirely my own.

Since the late 1960s, many individual designers and makers of jewellery have been consistently demonstrating that jewellery and other objects of personal adornment have few limits in terms of scale, materiality and wearability. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the emergence of contemporary jewellery has produced a vast array of interesting, exciting and sometimes baffling approaches to the adornment of the body. For the student, there are now a growing number of exhibitions, books, periodicals and online sources that critique the role of jewellery in contemporary culture. Indeed, the advent of post-modern culture (and other cultural positions that claim to have supplanted it) has had its effect on jewellery as much as on other aspects of design and visual culture in recent years.

However, those who wish to consider the cultural and critical context of modern jewellery in the early part of the twentieth century are less well served. In particular, the position of the decorative arts in relation to the culture of modernism still remains relatively underexplored and jewellery fares particularly badly. As far as the 1920s and 1930s is concerned, the general tendency to label developments in modern jewellery (and sometimes any other kind of jewellery made during this period) as art deco severely limits the possibility of a much wider understanding of the relationship between jewellery, adornment and what lies beyond. This book, therefore, is not overly concerned with identifying styles and approaches that have already been very well described by others. Rather, it attempts, in its five chapters, to consider how the culture of modernism in Europe and America made its impact felt on jewellery through an examination of issues of gender, identity, modernity, materiality, representation, consumption and display.