Reckoning with Matter

Calculating Machines, Innovation, and Thinking about Thinking from Pascal to Babbage

MATTHEW L. JONES

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2016 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2016.

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-41146-0 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-41163-7 (e-book)

DOI : 10.7208/chicago/9780226411637.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jones, Matthew L. (Matthew Laurence), 1972 author.

Title: Reckoning with matter: calculating machines, innovation, and thinking about thinking from Pascal to Babbage / Matthew L. Jones.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016015339 | ISBN 9780226411460 (cloth: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226411637 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: CalculatorsHistory. | ComputersHistory. | TechnologyHistory.

Classification: LCC QA 75. J 66 2016 | DDC 510.28/4dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016015339

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To my parents, Wally and Pru, and my sister, Lindsay

I shall not stop to examine either the Wisdom or the Morality of these several Propositions; my Object in this part of this Logical Investigation, being simply to shew by means of specifick Examples, in what Manner, a Piece of Mechanism can delve into the Mind of Man and discover the inmost Recesses of the Human Heart .

CHARLES STANHOPE , c. 1800

Contents

This scientific invention has been, at all times, and particularly in the last two centuries, an object of serious but fruitless meditations by eminent men.

ADVERTISEMENT FOR ARITHMOMETER OF THOMAS DE COLMAR , 1870

Inventing the machine proved far more taxing than Babbage had envisioned. Half a lifetime of labor left no completed machines.

Babbage was the latest in a two-hundred-year line of philosopher-engineers whose hubris about the triviality of mechanical invention was bound to their desire to grasp, improve, and rationalize that processwhat Babbage called Francis Bacons hope for the discovery of a philosophical theory of invention. Making calculating machines always proved more taxing than their inventors envisioned. This book studies failed efforts to contrive calculating machines, alongside their creators reflections on the inventive process. In the accounts of their efforts that follow, a descending bassline of philosophical hubris checked again and again over two centuries accompanies the melodies and motifs of schematic ideas and clever contrivance, of second-order reflection on the nature of inventive labor, of the coordination of mind and hand, of the labor history of invention, and of the prehistory of intellectual property and of creative genius.

This book studies the complicated, failure-prone, largely unused machines in the period before they became everyday commodities, from the attempts of Pascal in the 1640s through Babbages efforts in the 1820s1840s. Copies and counterfeits, as well as profoundly innovative and improved machines, proliferated throughout the period, though none was manufactured in any number.reveal central features of aesthetic and legal debates of the early-modern period. I look at conceptions of invention right up to the instauration of modern patent regimes and the solidification of the concept of Romantic genius. Considering the makers of calculating machines highlights the varied early-modern ways of understanding and rewarding creative making that drew upon earlier creations, in the moment before imitation came to be seen as antithetical to original creation rather than integral to the inventive process. These conceptions of creativity and making are often more incisiveand more honestthan those still dominating our own legal, political, and aesthetic culture. Ultimately, Reckoning with Matter uses these machines, with their dense accumulations of documentation, as recording instruments that track major contingencies of European early modernity, from its economic history to its visions of creative activity itself.

Carry, Numeracy, and the Debased Status of Computation

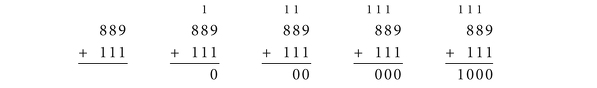

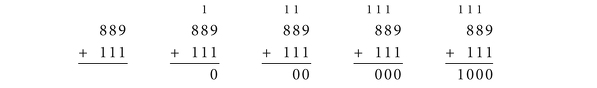

Threaded through this study is the story of efforts to mechanize a skill ubiquitous in postindustrial society: the process of carrying ones in addition. If Jane has 889 apples and Sven gives her 111, she has 1,000 apples. Using a discipline of mind and hand central to primary education, most of us perform this operation by adding 9 to 1, writing 0 below the 1, and performing a carry by putting a 1 above the 8 in the tenths place. Adding the 8 and two 1s in the tenths place produces another carry, duly marked in the hundreds place. Ditto for the hundreds.

The first carry itself causes a carry, which in turn causes another carrythis is called the propagation of carry. We could do this all day, until we got bored or lost attention or found a child to do it for us. The difficulty of making a mechanicalor electronicapparatus perform this corporeal-mental operation reliably, securely, cheaply, and speedily is the warp running through all the chapters that follow. In every case, philosopher-inventors underestimated the challenge of mechanizing carry.

Relatively few people in early-modern Europe possessed this skill or equivalent ways of performing addition, such as using an abacus. In his 1673 pamphlet for his calculating machines, Samuel Morland appended a short introduction to the four operations of basic arithmetic, so to render them plain Despite their ever-greater importance in commercial transactions, navigation, and taxation, the ability to perform sophisticated arithmetic, algebra, and accounting operations was the province of a narrow stratum of commercial and governmental elites.

Reckoning belonged primarily to commercial orders and not to aristocracies of arms or aristocracies of the mind. Even natural philosophers and geometers typically viewed reckoning askance, as a mechanical activitya mental one, to be surelow on the totem pole of knowledge. Algebra suffered from the taint of the mechanical: Ren Descartes insisted that his new geometry, reworked with his form of algebra, had nothing to do with the mechanical logistic of the commercial classesa claim as revealing as it was untrue.

The debased, mechanical reputation of computation contributed greatly to the iconoclastic edge of Thomas Hobbess notorious reduction of thinking to reckoning: By Ratiocination, I mean computation. Now to compute is either to collect the sum of many things that are added together, or to know what remains when one thing is taken out of another. Ratiocination, therefore, is the same with addition and subtraction.

In recent years, many philosophers and philosophically inclined scientists have speculated about the possibility of reducing all mental operations to mechanical computation. The same penchant should not be projected into the early-modern period. Given that computation was accorded such a lowly status among mental activities, the mechanization of reckoning, however impressive, was rarely seen as powerful evidence that the mind could be reduced to mechanism. For mechanical computation to threaten an incorporeal mind seriously, something like Hobbess reduction of thought to calculation was required. Few in the seventeenth century accepted such a reductionfewer still in the eighteenth century, despite the growth of materialism and algebraic analysis alike. Like our contemporaries who seek to demonstrate domains of human competence not replicable by an algorithmic machine, most early modernsincluding the most godless materialistssaw thinking as something irreducible to calculation.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).