In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

From John

To my family

Engineers view their profession as fascinating, creative, and full of interesting challenges. Those outside engineering often regard it as repetitive, mechanical, and frustrating.

What is evident from both perspectives is that engineering is complex. It requires an intensive core of knowledge in mathematics, physics, and chemistry, the exploration of which fills most of the first two years of the college curriculum. In focusing on these elements, the curriculum tends to provide very little context. When I was a beginning engineering student, I found it frustrating that the calculations and abstract concepts I was learning in the classroom were difficult to tie to real-world application. The engineering curriculum gave me a lot of trees, and very little forest.

101 Things I Learned in Engineering School flips this around. It introduces engineering largely through its context, by emphasizing the common sense behind some of its fundamental concepts, the themes intertwined among its many specialties, and the simple abstract principles that can be derived from real-world circumstance. It presents, I believe, some clear glimpses of the forest as well as the trees within it.

It is my hope that this book will interest and enlighten college students seeking context for their developing mathematical and scientific knowledge, inspire practicing engineers to reflect on the subtle relationships in their field, and encourage the lay person to see the engineering world as engineers dofascinating, creative, challenging, collaborative, and unfailingly rewarding.

John Kuprenas

From John

Thanks to Weston Hester, Keith Crandall, Ben Gerwick, William C. Ibbs, Povindar K. Mehta, David Blackwell, the inspiration of the books at Skylight and Powells, and the conversations at Figaro Caf.

From Matt

Thanks to Karen Andrews, Nicole Bond, Regina Brooks, Nancy Byrne, Sorche Fairbank, Venkataramana Gadhamshetty, Meredith Haggerty, Harmonie Hawley, Dylan Hoke, Dave McNeilly, Jamie Raab, Aaron Santos, Simon Schelling, Kallie Shimek, Rekha Ramani, Nick Small, Flag Tonuzi, Tom Whatley, and Rick Wolff. Special thanks to Marshall Audin, Myev Bodenhofer, and David Mallard for their ideas, help, and support.

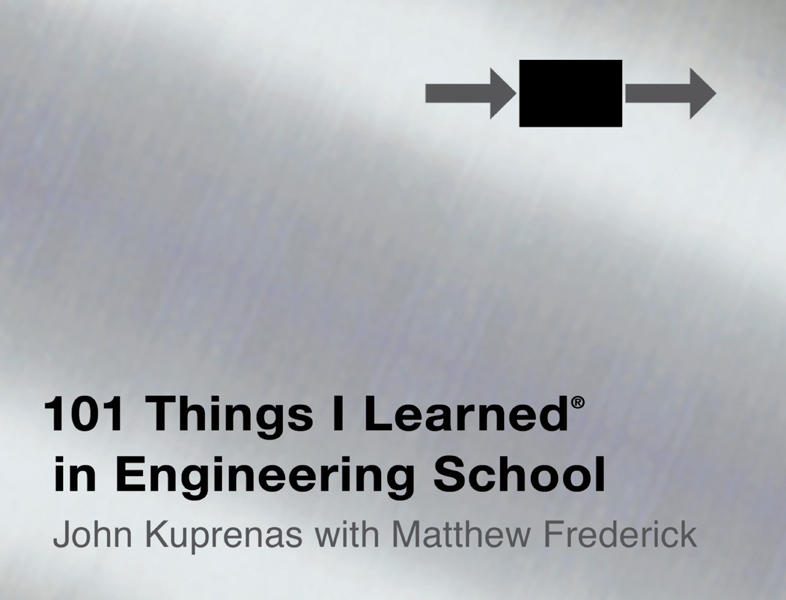

A black box is a conceptual container for the knowledge, processes, and working assumptions of an engineering specialty. On multidisciplinary design teams, the output of one disciplines black box serves as the input for the black boxes of one or more other disciplines. The designer of a fuel system, for example, works within a fuel system black box that produces an output for the engine designer; the engine designers black box outputs to the automatic transmission designer, and so on.

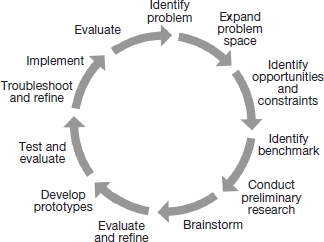

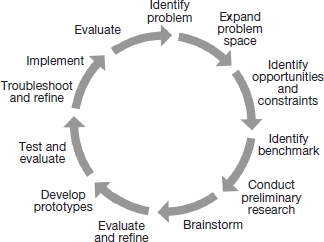

Design solutions dont emerge linearly, however, and design teams work in interconnected webs of relationships. Hence, the black box model works best when employed as a momentary ideal that is adjusted and redefined throughout the design process as constraints become evident, opportunities emerge, prototypes are tested, and goals are clarified. It fails when expected to be permanent and orderly.

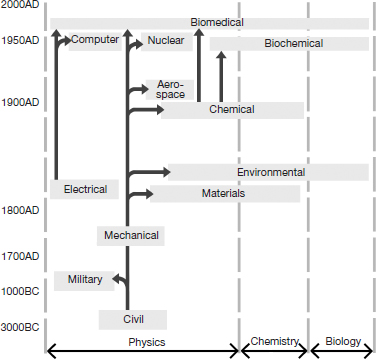

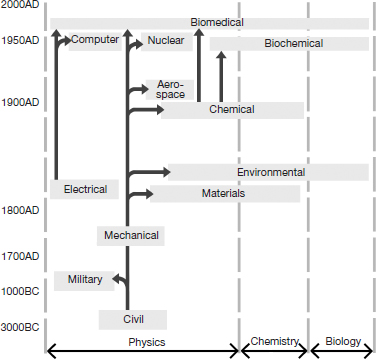

Engineering family tree

In its early days during the Roman Empire, civil engineering was synonymous with military engineering. Their kinship was still strong when the first engineering school in America was founded in 1802 at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York. USMA graduates planned, designed, and supervised the construction of much of the nations early infrastructure, including roads, railways, bridges, and harbors, and mapped much of the American West.

School may teach the numbers first, but calculation is neither the front end of engineering nor its end goal. Calculation is one means among many to an endto a solution that provides useful, objectively measurable improvement.

Every problem has embedded in it a hooka familiar, elemental concept of statics, physics, or mathematics. When overwhelmed by a complex problem, identify those aspects of it that can be grasped with familiar principles and tools. This may be done either intuitively or methodically, as long as the tools you ultimately use to solve the problem are scientifically sound. Working from the familiar will either point down the path to a solution, or it will suggest the new tools and understandings that need to be developed.

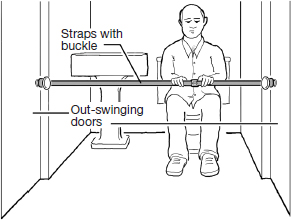

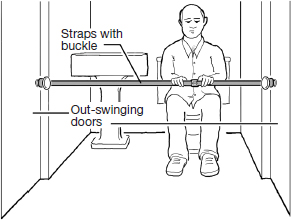

How the former Hotel Louis XIV in Quebec prevented guests from locking each other out of the shared bathrooms

Engineering problems rely on the familiar, but invention is also called for. Some problem-solving tools are developed through rote and repetition; some emerge intuitively; some rote-learned tools become intuitive over time; and some come out of necessity and even desperation. Add the tools you develop from solving each problem to your toolbox to use on future problems. More importantly, add to your toolbox the methods by which you discovered the new tools.

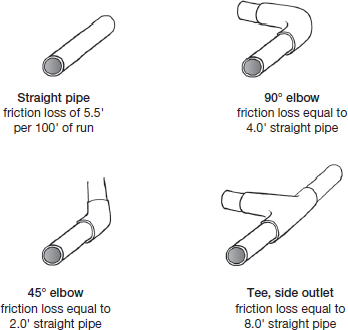

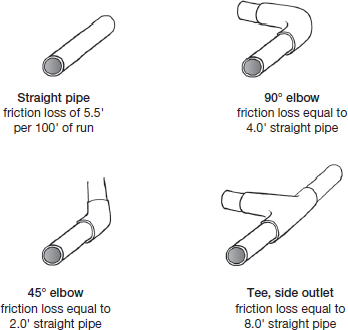

The problem of calculating pressure loss can be simplified by converting components to an equivalent length of straight pipe. (Assumes 1 dia. PVC pipe at 30 gallons per minute initial flow)

Inside every large problem is a small problem struggling to get out.

TONY HOARE

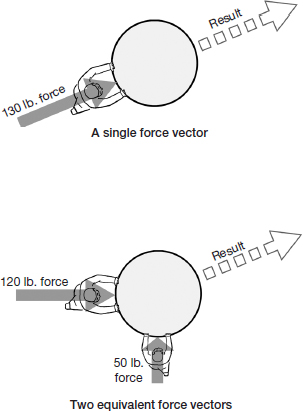

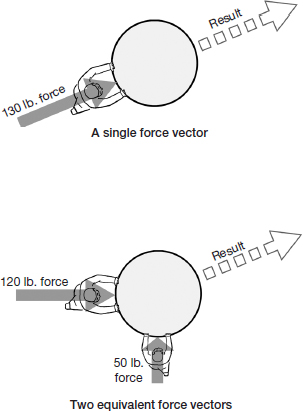

A force is expressed graphically by a vector. A vectors length is its magnitude, and its direction is given in relation to the x, y, and z axes. Every person has a gravity force vector with a magnitude measured in pounds or newtons, and a direction toward the center of the earth. Any single vector can be replaced by more than one component vectors, and vice versa.